Nihil Obstat: Robert S. Pelton, C.S.C. Censor Deputatus

Imprimatur: W Leo A. Pursley, D.D., Apostolic Administrator of the Diocese of Fort Wayne, Indiana April 20, 1956

Copyright 1980 by Peter Thomas Rohrbach.

Originally published in 1956 by Fides Publishers, Chicago, Illinois and later reprinted by Fides in conjunction with Our Sunday Visitor. Reprinted with the present preface in 1980 by Four Courts Press, Dublin, Ireland. The present printing is taken from the Four Courts Press edition.

ISBN: 978-0-89555-180-1

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

TAN Books

An Imprint of Saint Benedict Press, LLC

Charlotte, North Carolina

2012

TO

OUR LADY OF MOUNT CARMEL

WHO WATCHES OVER US WITH EXQUISITE TENDERNESS,

GUIDES US WITH UNERRING PRECISION, AND PROCURES

FOR US MYRIAD HAPPINESS

THIS BOOK IS AFFECTIONATELY AND

GRATEFULLY DEDICATED

Do not be astonished at the difficulties one meets in the way of mental prayer, and the many things to be considered in undertaking this heavenly journey. The road upon which we enter is a royal highway which leads to Heaven. Is it strange that the attainment of such a treasure should cost us something? The time will come when we shall realize that the whole world could not purchase it.

St. Teresa of Avila

Preface to the 1980 Edition

T HE WORLD has changed in many ways since the initial publication of this book, but the fact that it continues to be published in edition after edition over the years suggests that there might very well be something quite changeless about what the book discusses .

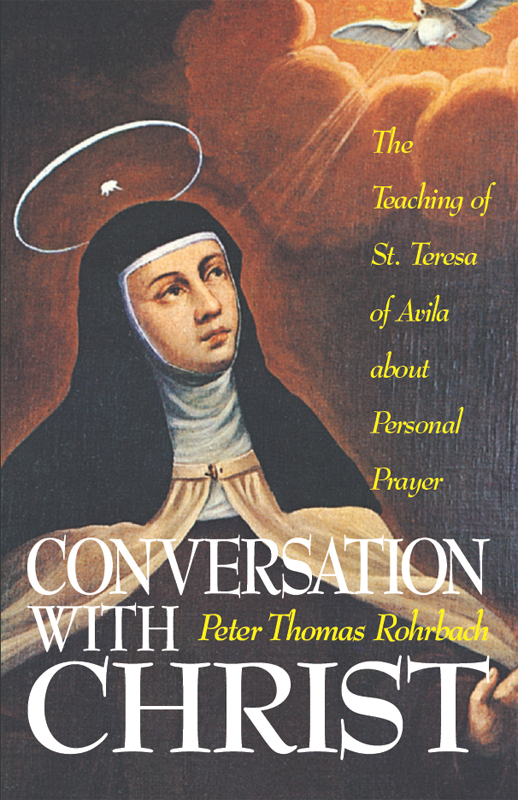

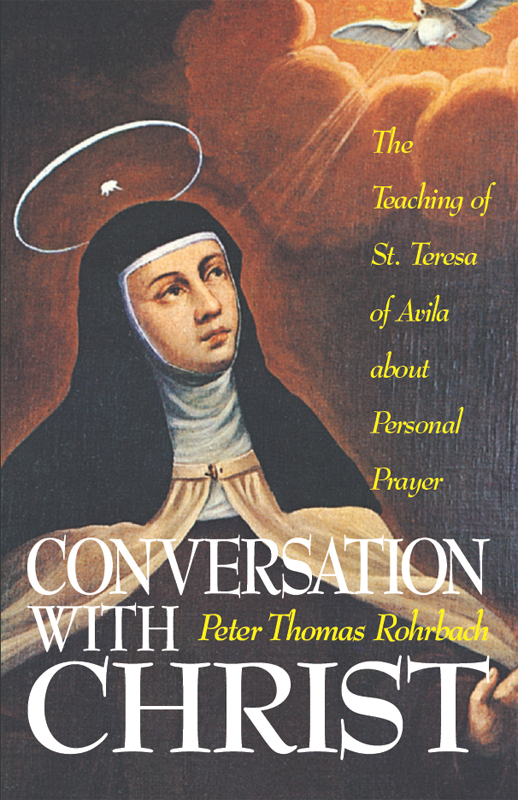

Conversation with Christ is an attempt to explain and outline St. Teresa of Avilas teaching about personal prayer, first described by her so lucidly in her 16th century writings. Indeed, since the initial publication of this book, St. Teresa has been declared a Doctor of the Church, which is yet another testament to the validity and permanence of her teaching. However, her teaching about prayer is not something unique in the history of Christianity, a private and recondite doctrine, but rather it is an explanation of the basic doctrine about prayer as expressed in the pages of Scripture.

In the earliest pages of Scripture God is presented to us as a person , and as a person who desires to establish a relationship with his creatures. The primary vehicle of that relationship, as outlined in Scripture, was prayer, and the long biblical narrative is a continuing account of mankinds attempt to remain in faithful association with his God. The psalms, for instance, are a factual reportage of the ancient Jews prayers to God, demonstrating how those early believers worshipped Yahweh, how they expressed their gratitude to Him, how they sought His assistance, and how they evidenced their love for Him.

Jesus, entering the scene of human history, continued to emphasize that vital necessity of prayer for an authentic religious life, both in His teaching and in the practical example of His life. In the few years of His public ministry, Jesus was involved in an extremely active life, teaching and healing and laying the foundations of Christianity, but He was simultaneously a dedicated Man of prayer. We see Him stealing away from the crowds to give Himself to private prayer, even spending whole nights in prayer or rising early before His disciples to pray alone. He taught His disciples the Lords Prayer, and He frequently commented on the value and the efficacy of prayer. But when you pray, go to your private room, He said, and when you have shut the door pray to your Father in the secret place.

What St. Teresa has done so brilliantly is to describe precisely how a person can indeed contact God through prayer. Despite her reputation as a soaring Spanish mystic, she was an eminently practical person, and that practicality shines through her teachings about prayer: she is an instructor who shows, in step-by-step fashion, how the individual can contact God and then sustain that relationship.

It is also important to note that St. Teresa argues for the necessity of both private and liturgical prayer. And, again, this represents fidelity to the scriptural message: Jesus was a Man of private prayer, but He also prayed publicly with his disciples, particularly at the Last Supper. This is a critical point to note today when there seems to be a lessening enthusiasm in some quarters for what we call mental or private prayer. Vatican Council II addressed that question sharply in the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy when it stated: The spiritual life, however, is not confined to participation in the liturgy. The Christian is assuredly called to pray with his brethren, but he must also enter into his secret chamber to pray to the Father in secret.

As a matter of fact, St. Teresa chided as a fundamental distinction between private and public prayer: for her, all prayer should entail contact with God, and if any form of public prayer did not involve that contact then it was not, in her terms, prayer. Her teaching, therefore, tells us how to contact God, whether it is expressed privately or in communion with others. More modern religious authors have termed this experience an effort of conscious communication with God. Teresa of Avila, in a now classic phrase of religious literature, called it a conversation with Christ . And she shows us the way to achieve it.

Peter Thomas Rohrbach

January 15, 1980

Contents

Chapter

Chapter

Part I

The Nature of Meditation

Prayer is conversation with Him.

St. Teresa

Chapter 1

The Purpose of Meditation

A GOOD DEAL of the confusion surrounding meditation results from a failure to recognize its basic, fundamental purpose. Simply stated, the aim of meditation is to provide a framework or setting for a personal, heart-to-heart conversation with Christ. If this primary goal is retained in mind throughout our entire discussion of meditation, much of the mystery will fade away.

St. Teresa sums up the whole matter with one magnificent sweep of the pen in her classical definition of mental prayer:

Mental prayer is nothing else than an intimate friendship, a frequent heart-to-heart conversation with Him by whom we know ourselves to be loved.

Therefore, all that precedes meditation, all that accompanies it, and all that follows it, has for its primary aim the stimulation of this conversation with Christ. Let us repeat it again for it is of extreme importancemeditation, in its final analysis, should be basically a friendly conversation with Christ.

The practice of meditation has assumed frightening proportions in the minds of many. It is regarded warily as some type of mental workout which leaves one better prepared to serve God, a spiritual setting-up exercise. The assumption, therefore, is that meditation is intended only for intellectuals, and is definitely not something to be undertaken rashly by those further down the intellectual ladder. Nothing could be further from the truth; meditation is for all, university professors, and grade school graduates alike

First of all, the word meditation. The term is confusing; for in this conversation with Christ, meditation is only one part of the process. By entitling the entire procedure meditation, we are in effect calling the whole by one of its parts. St. Teresa preferred to designate the process mental prayer, and in her writings one finds the terms mental prayer and prayer predominantly employed in place of meditation. But to preclude further difficulty, we will continue to designate the entire process by the more widely accepted term meditation, with the tacit reservation that meditation is but one of the divisions of mental prayer. In following this pattern, we will here employ the word consideration for that part of prayer which is specifically the meditation.

Next page