Memoirs of a Dervish

Also by Robert Irwin

NON-FICTION

The Middle East in the Middle Ages:

The Early Mamluk Sultanate 12501382

The Arabian Nights: A Companion

Islamic Art

Night and Horses and the Desert:

An Anthology of Classical Arabic Literature

The Alhambra

For Lust of Knowing: The Orientalists and Their Enemies

Camel

Mamluks and Crusaders

Visions of the Jinn: Illustrators of the Arabian Nights

The New Cambridge History of Islam, vol. 4 Islamic

Cultures and Societies to the End of the Eighteenth

Century (editor)

FICTION

The Arabian Nightmare

The Limits of Vision

The Mysteries of Algiers

Exquisite Corpse

Prayer Cushions of the Flesh

Satan Wants Me

Memoirs of a Dervish

ROBERT IRWIN

First published in Great britain in 2011 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3A Exmouth House

Pine Street

Exmouth Market

London ECIR OJH

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright Robert Irwin, 2011

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset in Sabon by MacGuru Ltd

info@macguru.org.uk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Clays, Bungay, Suffolk

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 86197 991 9

eISBN 978 1 84765 404 5

The paper this book is printed on is certified by the 1996 Forest Stewardship Council A.C. (FSC). It is ancient-forest friendly. The printer holds FSC chain of custody SGS-COC-2061

To Helen, who rescued me from myself

The default setting of a memoir is yearning. Biography and autobiography tell the story of a life, but a memoir conjures a ghost image: the adventure missed, the love refused, the road not travelled, the might-have-beens. Perhaps memoir writing is itself a kind of adventure: a process as much of forming as describing.

Jane Shilling reviewing Luke Jenningss memoir Blood Knots

in the Daily Telegraph, 24 April 2010

CONTENTS

PREFACE

WHY DID I WRITE THIS BOOK? The causes are multiple. First, I badly wanted to create a work of literary art and perhaps also to give my youth a retrospective artistic shape. Then I wanted to know where I stood, both in relation to the mystical states I experienced as a young man and in relation to my eventual death and judgement. But I also wanted to give an account of Sufism from the inside, as well as instructing readers in the basic elements of Islam and the difficulties a Western convert is likely to face. At the same time I wanted to give an impression of how it felt to be young in the hippy sixties from the perspective of someone who was not part of the underground countercultural elite. In particular, I wanted to shed some light on the occult and mystical aspects of the counterculture, as well as some of the ludicrous and half-witted aspects of the hippy sixties. Additionally this is the story of someone who sat at the feet of a series of remarkable teachers. It is a book about teacherstudent relations and, if Lynn Barber had not already taken the title for her excellent memoir, I might have called my book An Education.

There is a lot about dreams in this book, and it is as Sigmund Freud might have put it overdetermined. In Freuds The Interpretation of Dreams, a dream is said to be overdetermined if its plot and its various images are based on multiple causes. So in a dream the rocking horse in the corner of the attic may draw upon a glimpse of a rocking horse in a toyshop in the course of the previous day, but at the same time it may also allude to a deeply repressed childhood trauma, conceivably something as serious as sexual molestation. A dream is compounded of many elements coming from different levels of the psyche and a successful interpretation requires understanding of the dreams images at several levels.

Over the decades my memories my dreams of the sixties coalesced into a kind of demon that lurked inside me. But I have found the writing of Memoirs of a Dervish to be a kind of exorcism. Something has been set free. I am not yet sure what.

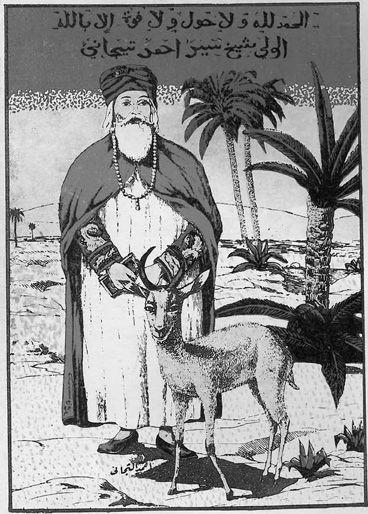

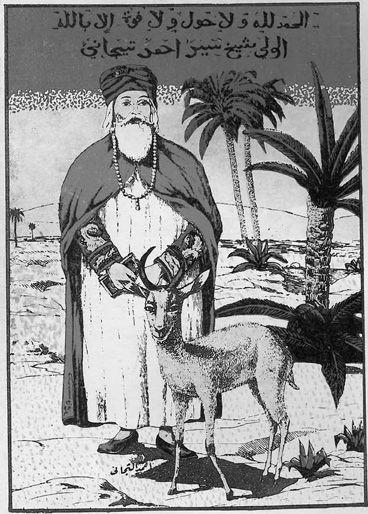

1. The eighteenth-century Sufi Shaikh Ahmed Tijany

OXFORD

IT WAS IN MY FIRST YEAR at Oxford that I decided that I wanted to become a Muslim saint. I wish I could remember more. I do remember that early in the Hilary term of 1965, when it was still cold and there was snow on the ground, Ralph Davis, one of Mertons history tutors, set me to write an essay on the early Franciscan Order. I cannot recall what the title was, but I guess that I was being asked to judge the degree to which the original spirit and aims of St Francis were preserved as the order he had founded became increasingly institutionalised. The required reading consisted mostly of primary sources, medieval accounts of the saints life. These included lives of St Francis by Thomas of Celano and St Bonaventure, as well as something called The Little Flowers of St Francis, which sounded as though it would be just soppy, but which turned out to be a fascinatingly astringent document.

To be studying the Middle Ages in such a medieval environment was a curious form of total immersion. Merton had been founded in 1264 and early members of the college had taken part in the great metaphysical debate between two famous Franciscan philosophers, Duns Scotus and William of Ockham. On the upper floor of the colleges medieval library books bound in leather or vellum were still chained to the shelves. The grace before dinner was and is in Latin. The central part of the college is built around quadrangles and the stonework of the oldest buildings glows golden under the sun. Davis occupied a set of oak-panelled rooms in Fellows Quad and his tutorials were conducted like scholastic disputations. So that in each essay I was supposed to put forward a thesis to which in response he would propose a counter-thesis. It did not matter what I might argue; he would always have the counter-argument ready. He was the master of what looked like childishly simple-minded questions, but those questions were used to great effect in the demolition of undergraduate would-be sophistication.

The narrative of The Little Flowers (Fioretti) teemed with miracles and acts of intense piety. St Francis almost went blind from weeping. He ate nothing but half a loaf of bread while fasting through Lent. He converted the wolf of Gubbio. At night he spoke with Christ in the woods and before his death he received the stigmata. But from almost the beginning there were also backbiting and execration. On one occasion the Devil possessed the body of an angry friar. The Devil also appeared in the guise of Christ to a certain Brother Ruffino and told him that he was damned. Brother Elias pride and ambition were a great torment to St Francis and he knew in spirit that Brother Elia was damned and was to leave the Order. As I struggled with my essay about the compromises that medieval mystics and ascetics had to make with more worldly people, I did not guess that I should soon be entering a very similar world and that the time of miracles was only months away. My future teachers in North Africa would instruct me in matters that were not on any university syllabus.

Next page