Exodus

Judaism, Christianity, and Islam Tension, Transmission, Transformation

Edited by

Patrice Brodeur

Alexandra Cuffel

Assaad Elias Kattan

Georges Tamer

Carlos Fraenkel

Volume

Exodus

Border Crossings in Jewish, Christian and Islamic Texts and Images

Edited by

Annette Hoffmann

ISBN 9783110616613

e-ISBN (PDF) 9783110618549

e-ISBN (EPUB) 9783110617085

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

2020 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Introduction

Annette Hoffmann

Scientific debates in the humanities centring on border crossings and cultural exchanges between Judaism, Christianity, and Islam have dramatically increased over the last decades.

Border crossings, however, cannot occur without borders. The latter demarcate geographical, chronological, political, or social entities and/or identities, which have been identified as different from each other. Demarcating borders and passing over them is a daily human practice, as Martin Heintel and others have recently underlined.

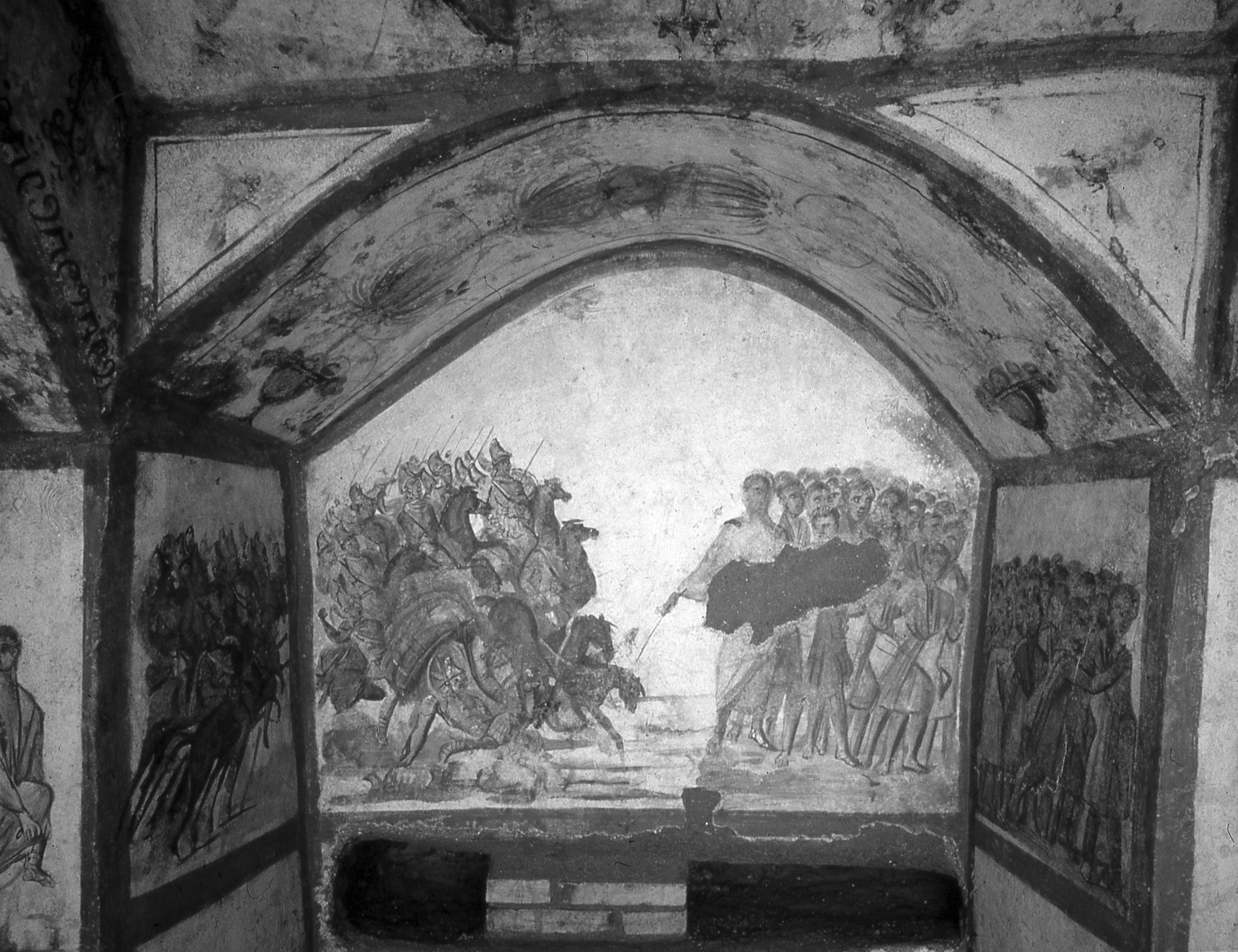

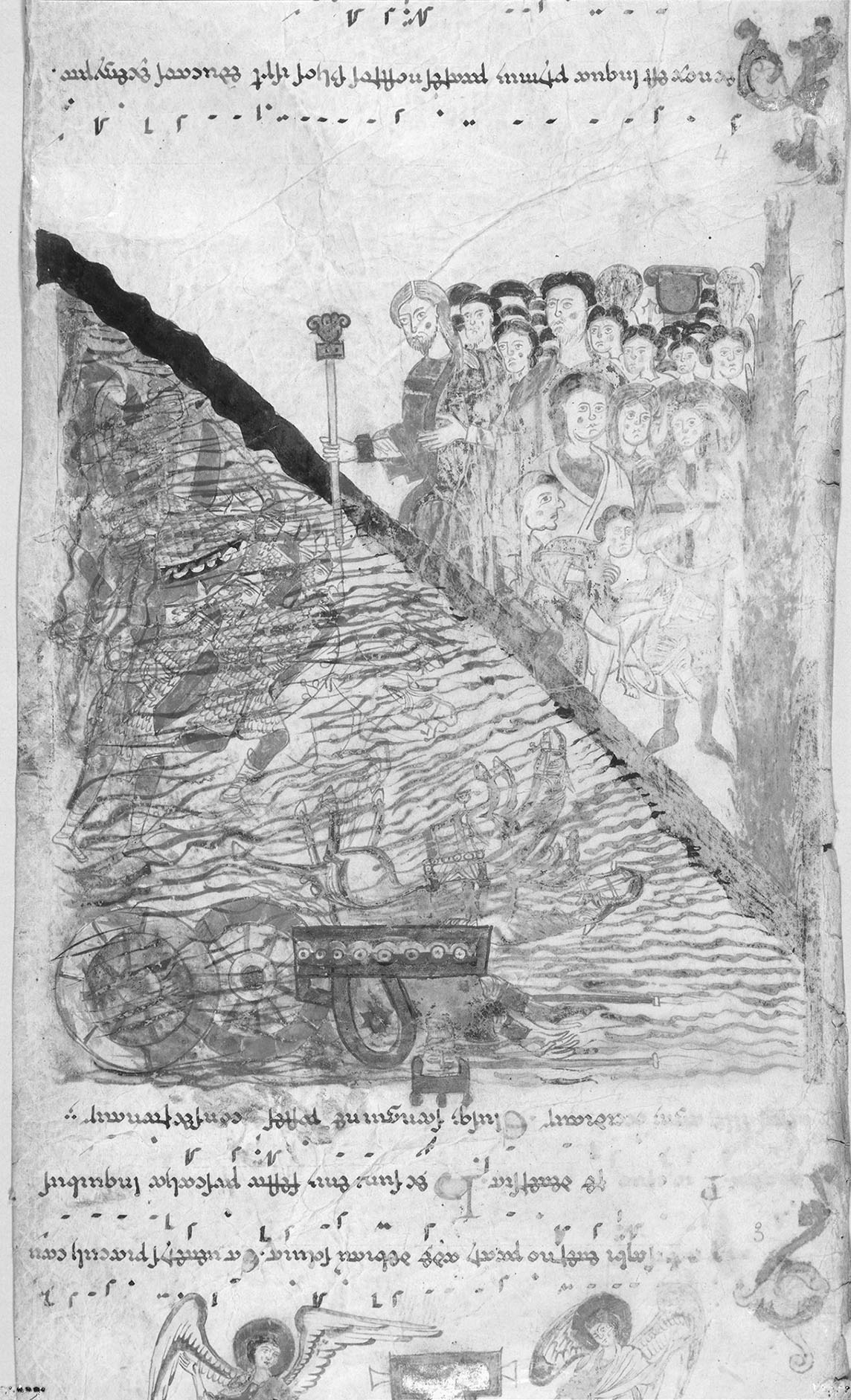

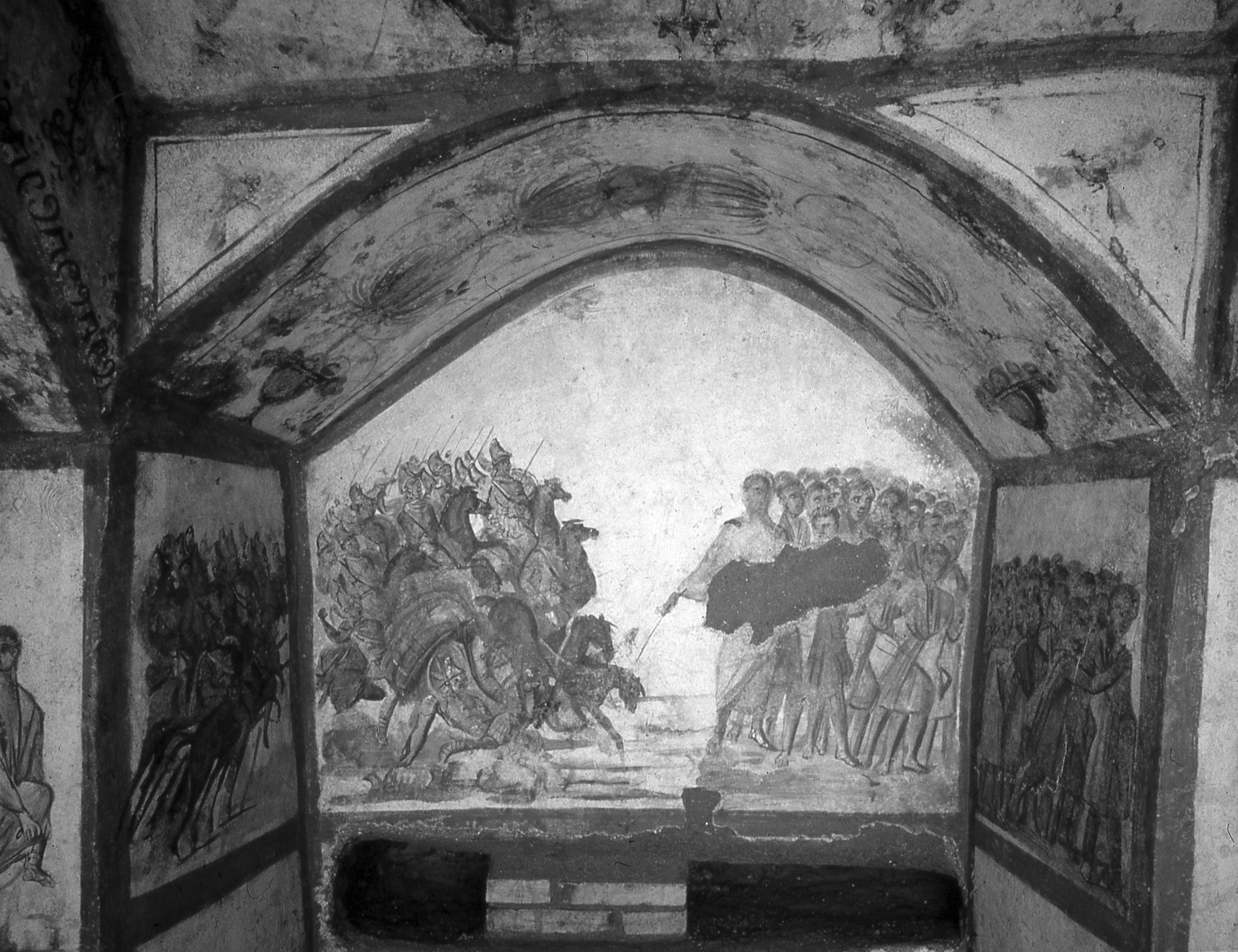

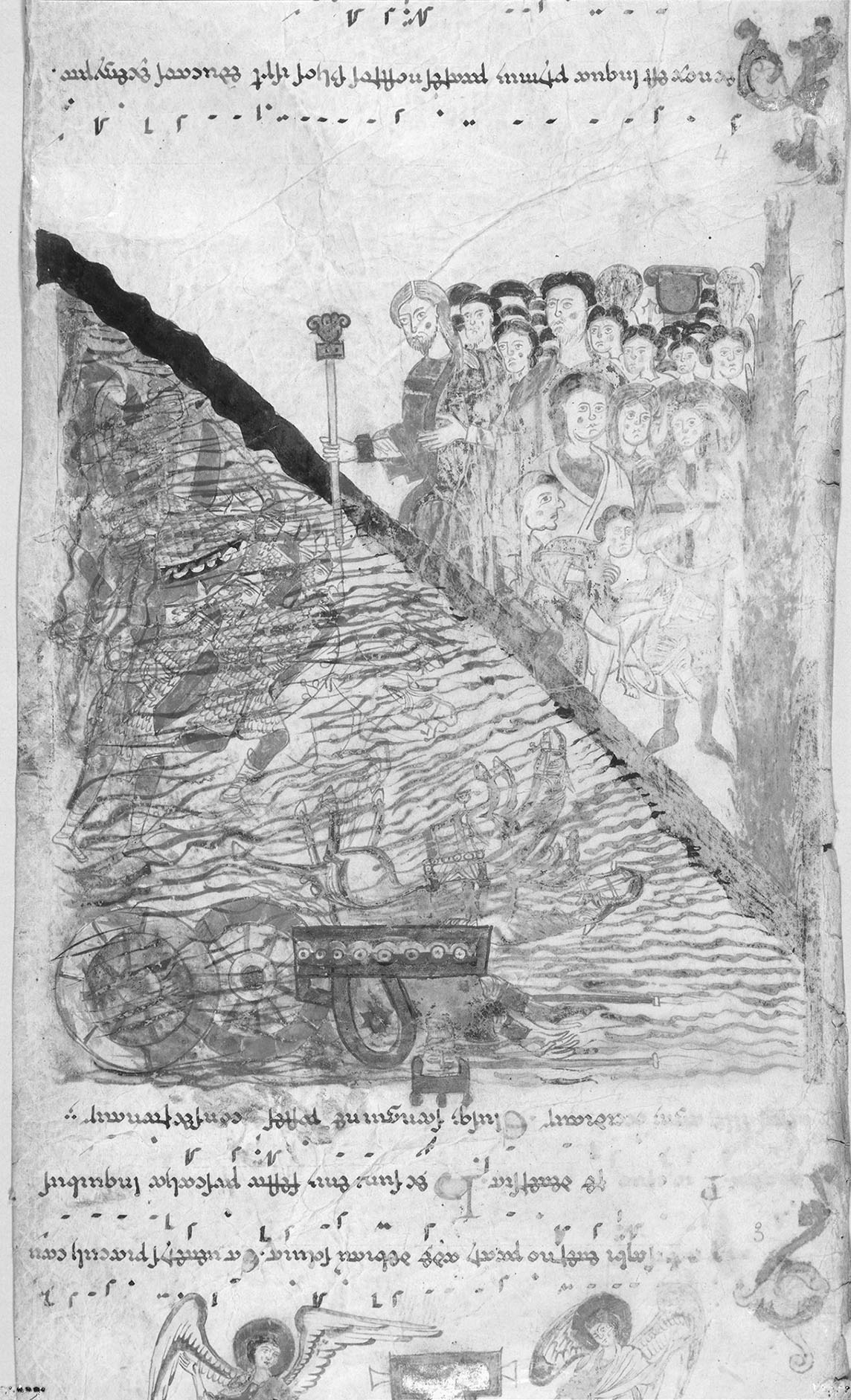

The Crossing of the Red Sea, the miraculous parting and closing of the waters, is certainly not only a border crossing, a flight out of the state of vassalage, the demonstration of Gods power, but it is also a border demarcation between two different peoples: the Egyptians and the Israelites, or the saved and the drowning. This dichotomy has often been visually expressed. In the fourth-century fresco in the catacomb of Via Latina in Rome, for instance, a blank interspace between the Egyptians and the Israelites is emphasized at the images center, interrupted only by the arm and staff of Moses in the act of closing the waters (fig. 1). In a similar yet opposing way, the Italian painter of an Exultet roll from 1136 depicted the sea shore as a black bold line that diagonally divides the entire picture into two distinct parts: that of the saved and that of the drowning people (fig. 2). The miracle at the sea, moreover, constitutes a frontier within the Exodus narrative, namely between the Israelites exit from Egypt and their wanderings in the wilderness, or between deliverance and guidance into the Holy Land, as Christoph Dohmen and Matthias Ederer have recently pointed out. Thus, with the protagonists entry into the story, the narrative immediately turns into an account of a border crossing. Moses ambiguity, his liminal status, is already encapsulated in the image of him floating in a casket between two riverbanks (fig. 3).

Fig. 1: The Crossing of the Red Sea, fresco, 4th century. Rome, Catacomb of Via Latina

Fig. 2: The Crossing of the Red Sea, Exultet roll, 1136. Paris, Bibliothque Nationale de France, Ms. nouv. acq. fr. 710, n. 4

Fig. 3: The Finding of Moses, Jmi al-tawrkh of Rashid al-Din,Tabriz, ca. 13141315. Edinburgh, University Library, Arab. Ms. 20, fol. 9r

Since the tragic history of the SS Exodus 1947 with 4,500 Holocaust survivors on board, who just like Moses and those who were destined to die in the wilderness were not permitted to enter Palestine, the term Exodus (gr. , way out) has also become an epitome for refugee movements. In recent times an increasing number of publications titled Exodus have examined refugee flows and immigration issues following mainly illegal frontier crossings all over the world, from Indochina to Mexico. In this sense, the topic reveals its actual relevance. As of late, this is even more true in light of the fate of lifeboats in the Mediterranean, such as the Aquarius, Lifeline, Diciotti, and others, which immediately remind us of the SS Exodus. Some of the articles in this volume, to a greater or lesser extent, hint at the timeliness of this issue. Migrations and cultural exchange processes are being increasingly accompanied by perceptions of difference and acts of demarcation, which exhort to keep historical memory alive.

The impact and memory of the Exodus story in post-biblical texts and images lend themselves to intercultural comparative examination. Such an approach has partly been taken in exhibitions and edited volumes on the figure of Moses, for instance Jane

On the other hand, in Theology and Egyptology, seminal studies on Moses and the Book of Exodus have repeatedly brought to the fore the storys dichotomies, such as Jan Assmanns Moses der gypter (2000) and Die mosaische Unterscheidung (2003), establishing the distinction between true and false as core issues of monotheistic religion.

In dialogue with these studies, but also diverging from them, this volume contains eleven contributions on transitional processes as a core theme of the Exodus narrative. These articles have been written by leading specialists in biblical and Rabbinic literature, in the Quran, and in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic art and film history. By bringing these studies together, the volume takes a twofold approach. On the one hand, it concentrates on topics regarding border crossings in Exodus, offering a common basis upon which to address comparative problems, and, on the other, it permits a study of interreligious, transcultural phenomena. The Jewish, Christian, and Islamic Exodus traditions did not grow in parallel neither in texts nor in images but rather interdependently. Thus, the chosen title Border Crossings does not simply address the narratives content, but it also includes aspects of the migration of textual and visual motifs: the use of Jewish sources in Christian and Islamic texts, for instance, or Jewish adoptions of Christian iconography or Muslim means of expression and vice versa. How do Jewish, Christian, and Islamic texts and images read and retell the transitional aspects in the Exodus story, and on what levels do the different traditions interact? What differences and similarities can be found in the patterns of interpretation? What correlations can be observed between the concepts in texts and those in images within these various cultures? What role do the different media play? By raising these questions, the volume aims to stimulate discussion and contribute to a deeper understanding of contact points between Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, set against the background of a common narrative central within each tradition.

The volume opens with a contribution that considers the story of Israels exodus at the time of its scriptural composition. Wolfgang Oswald underlines the fact that the search for the historicity of the Exodus event led to the question of the historicity of the Exodus narrative being neglected. The oldest, pre-priestly part of the narrative (Ex 113), Oswald maintains, is neither a historical report, an adventure story, or a religious confession. It reworks a probably older Judean exodus tradition and deals with the legitimacy of dissolving ones state of vassalage. According to an antique legal construction, the so-called sacral release, this dissolution is only possible by symbolically entering into the vassalage of God. The subject of the narrative, thus, is not the geographical wandering of Israel from Egypt, but the stepping out of the state of vassalage and entering into that of independence. It concerns a social status in the framework of what can be called international law. Thus, the border crossing addressed by the story was, as Oswald shows, originally juridical.