Contents

Guide

Zeenah u-Reenah

Studia Judaica

Forschungen zur Wissenschaft des Judentums

Begrndet von

Ernst Ludwig Ehrlich

Herausgegeben von

Gnter Stemberger, Charlotte Fonrobert, Alexander Samely und Irene Zwiep

Band 96

ISBN 978-3-11-045950-0

e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-046103-9

e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-046044-5

ISSN 0585-5306

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress.

Bibliografic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliografic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

The English translation of Biblical passages is taken from The Tanakh: The Holy Scriptures by permission of the University of Nebraska Press 1985 by the Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia.

www.degruyter.com

To the Memory of

My Mother Hana Faierstein

My Mother-in-law Gladys Belsinger Eckhouse

My Sister Rivkah Riqui Faierstein

Proverbs , 31:1031

Acknowledgments

The support and encouragement of several friends made the long task of translation and editing easier and smoother. Prof. Zeev Gries of Ben Gurion University of the Negev first suggested that I undertake this project. His support and encouragement of my scholarship has had a significant and positive impact on my work. Prof. Jean Baumgarten of CNRS (Paris), and Rabbi Jerry Schwarzbard of the Jewish Theological Seminary Library were also helpful in a variety of ways, answering questions and reading early drafts. My thanks to all these friends for their encouragement and support in many ways large and small. The support and encouragement of my spouse, Ruth Anne, has made possible all of my scholarly work. My debt to her is beyond calculation.

My thanks to De Gruyter Publishers for publishing this work in their series Studia Judaica and to the editors of the series for accepting this work into this series. My thanks also to my editors, Dr. Sophie Wagenhofer, Dr. Eva Frantz, and Johannes Parche for their work in seeing this project through the publication process.

Morris M. Faierstein

Rockville, Maryland

Introduction

The sixteenth century was the great age of the printed Bible. Though Gutenbergs Bible is usually considered the first printed book, and many Bibles were published in the fifteenth century, it was the sixteenth century where the importance of the printed Bible reached its apogee. Scholarly editions and polyglot Bibles were prepared, but the most influential innovation was the widespread dissemination of the Bible in the vernacular. Spurred by the Protestant Reformation, the Bible was translated into numerous vernaculars and published in innumerable editions.

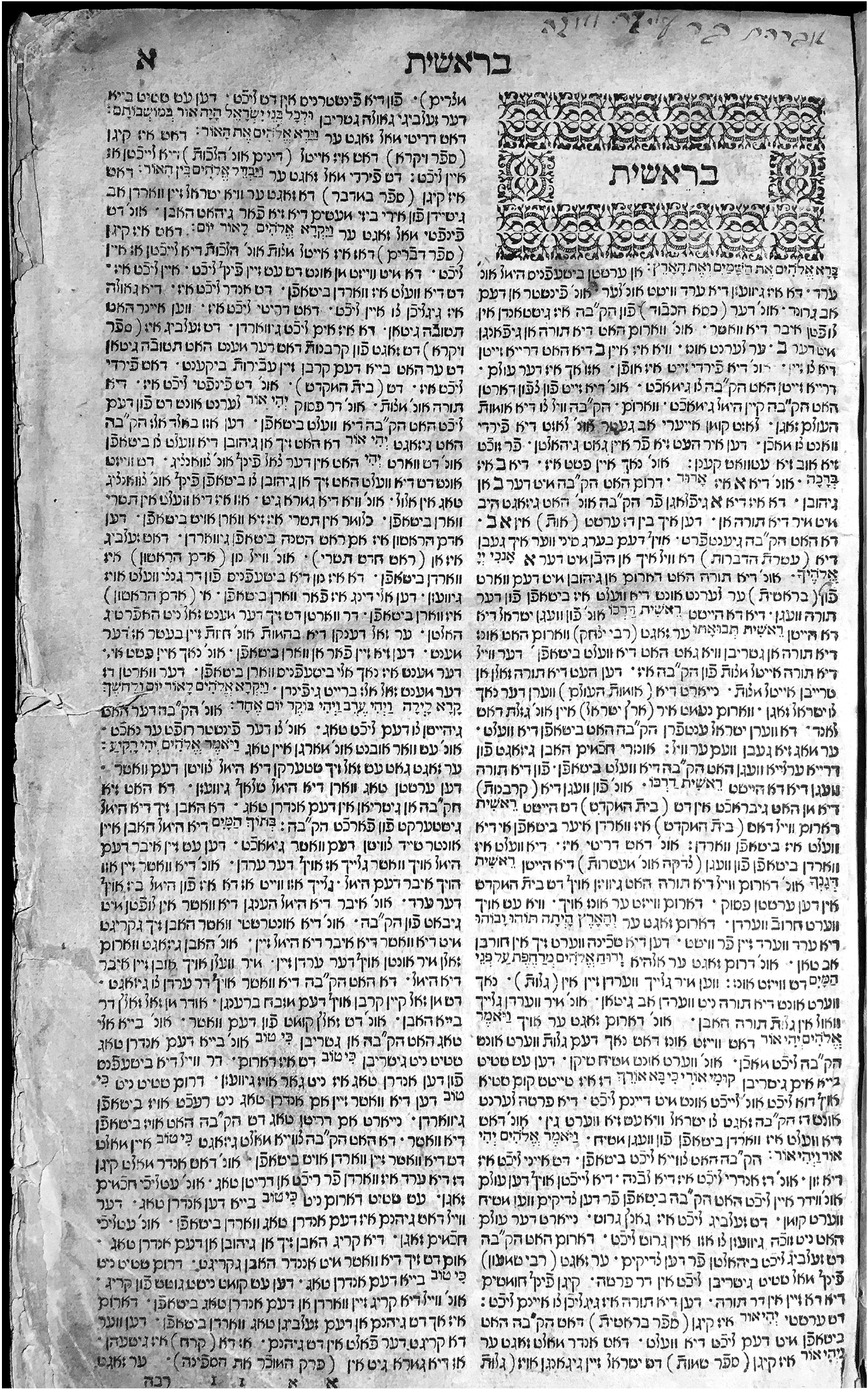

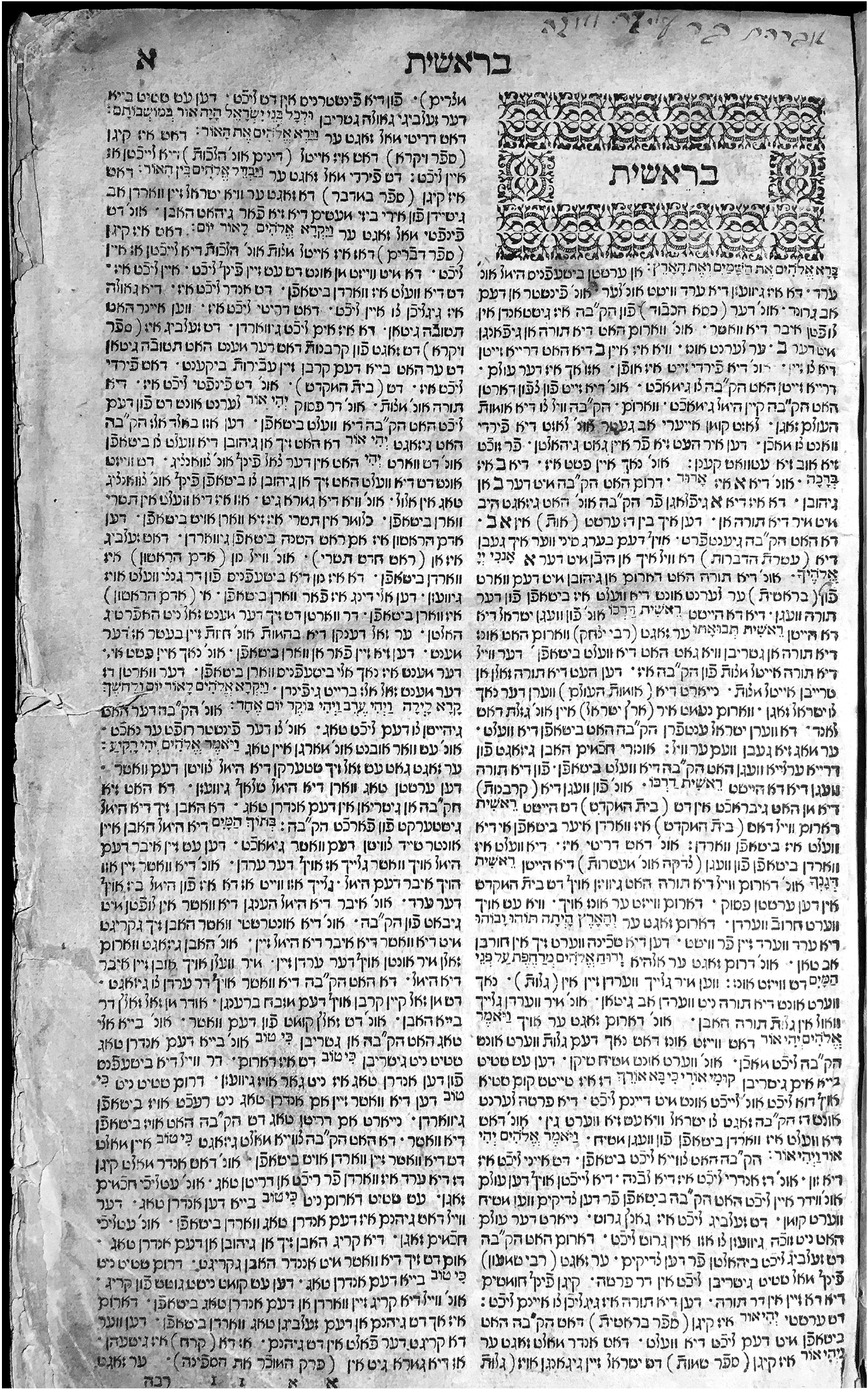

The Hebrew Bible was also widely printed in a variety of versions, including complete Bibles, Psalms, and other individual or collected Biblical books. For Jews, the primary Biblical format was the liturgical Bible. This is a uniquely Jewish construct consisting of those parts of the Bible that were part of the synagogue service. They include, the Humash [Pentateuch], Haftarot [passages from the prophets read after the Torah reading], and the five Megillot [Scrolls]. This work would also include a number of commentaries, more or fewer, depending on the edition. The addition of Rashis commentary, and the Targum of Onkelos were the basic additions. The first surviving printed Humash , published as early as 14871488 in Hijar, Spain followed this model. Daniel Bombergs Great Rabbinic Bible [ Mikraot Gedolot ], first published in 1516, became the standard for Jewish editions of the Humash , and the commentaries included in this and subsequent editions became canonical for future generations.

The printing of Yiddish books began sixty years after the first Hebrew books. The first Yiddish book printed was the Mirkevet ha-Mishneh , published in Cracow about 15341536. It was a concordance to the Bible that translated the Biblical Hebrew words into Yiddish. Its purpose was educational, as the introduction explains.

This educational justification for works in Yiddish became the template for many later Yiddish works and is found in the Introductions of many Early Modern Yiddish books published in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The next genre of Yiddish biblical work to be published was a Yiddish translation of the liturgical Bible. There were three editions in the sixteenth century, each published in a different place by a different editor and publisher. The first two editions were published in 1544. The first edition was by Paulus Fagius, an important Christian Hebraist, in Constance 1544.

Both Fagius and Aemilius published their Humash editions in two versions, one aimed at a Jewish audience and one aimed at Christian Hebraist scholars who were interested in understanding how Jews interpreted the text, so that they could better convince the Jews of the truths of Christianity.

All three editions, Constance, Augsburg, and Cremona follow the same translation method, from the Hebrew to the Yiddish, which is known as Humash with Hibbur and translations of the liturgical Bible based on this method are called a Teitsch Humash.

As Chava Turniansky described it,

The translations were meticulous word for word renderings of the text, they do not allow for any additions or omissions, they follow with extreme precision the consecutive order of the original without paying any attention to the requirements of Yiddish syntax.

The original purpose of this type of translation was pedagogical. It mimicked the way students were taught the text of the Humash and its Yiddish translation, and could almost be a transcript of the schoolmasters mode of instruction. This

A second popular rationale found in the Jewish Introductions of the Humash was the concept that reading these Humash translations was more worthwhile and religiously edifying than wasting ones time with chivalric romances that were popular among both Jews and Christians, like the romances of Dietrich of Bern and Hildebrand. The Introduction to Fagius Humash translation is an early example. He writes:

This book is likewise good for wives and young women who all know well how to read Yiddish, but who pass their time by reading worthless books such as Dietrich von Bern, Hildebrand and others like them which are nothing but lies and invented things. These wives and young women could read this Khumesh which is nothing but pure truth.

Another response to these concerns was a whole genre of Biblically inspired works that combined the appeal of Dietrich and Hildebrand with the piety of the Bible. The first two books in this category were the Shmuel Bukh (Book of Samuel) and Melokhim Bukh (Book of Kings), both first published by Paulus Aemilius in Augsburg, 1543 and 1544. Many of them were reprinted multiple times, but their popularity waned in the early seventeenth century.