2016 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

C 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Heinz, Anne M., editor. | Heinz, John P., 1936 editor.

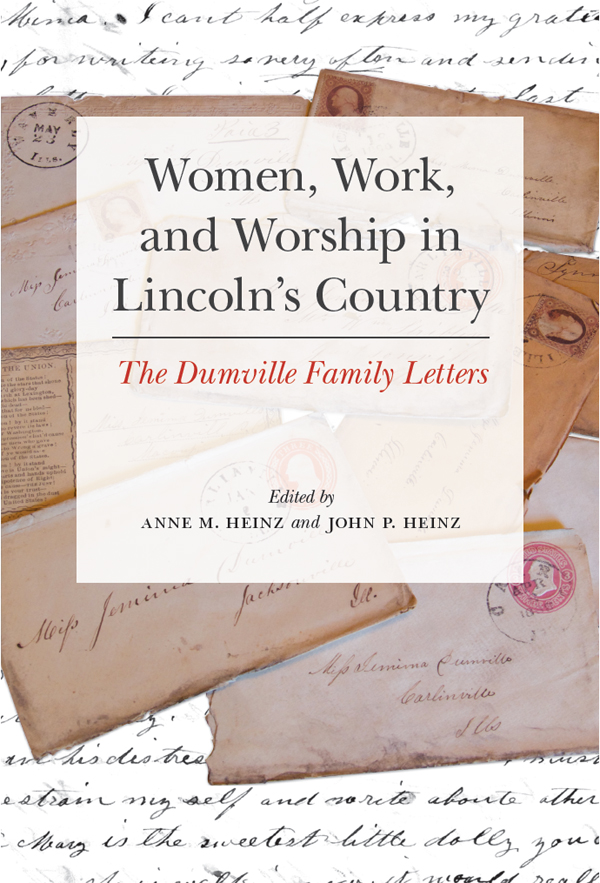

Title: Women, work, and worship in Lincoln's Country : the Dumville family letters / edited by Anne M. Heinz and John P. Heinz.

Description: Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield : University of Illinois Press, 2015. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015028396 | ISBN 9780252039959 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780252098130 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Dumville familyCorrespondence. | Lincoln, Abraham, 18091865Correspondence. | WomenMiddle WestHistory19th century. | WomenMiddle WestSocial life and customs19th century. | Middle classMiddle WestHistory19th century. | Middle WestHistoryCivil War, 18611865Social aspects. | Middle WestSocial conditions19th century.

Classification: LCC HQ1438.M53 W65 2015 | DDC 305.409773/09034dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015028396

Preface

The Provenance and Transcription of the Letters

The letters on which this book is based are held by the archives of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library in Springfield, Illinois. The collection includes ninety-four letters written by members of the Dumville familythe mother, three daughters, and the husband and children of the eldest daughter. In addition, there are twenty-three letters sent to them by neighbors, soldiers in the Civil War, and Methodist clergy. A few of the family letters appear to be copies or drafts of those that were sent, and some documents are also in the file. Of the 117 letters in the archive, one hundred are included here in whole or in part.

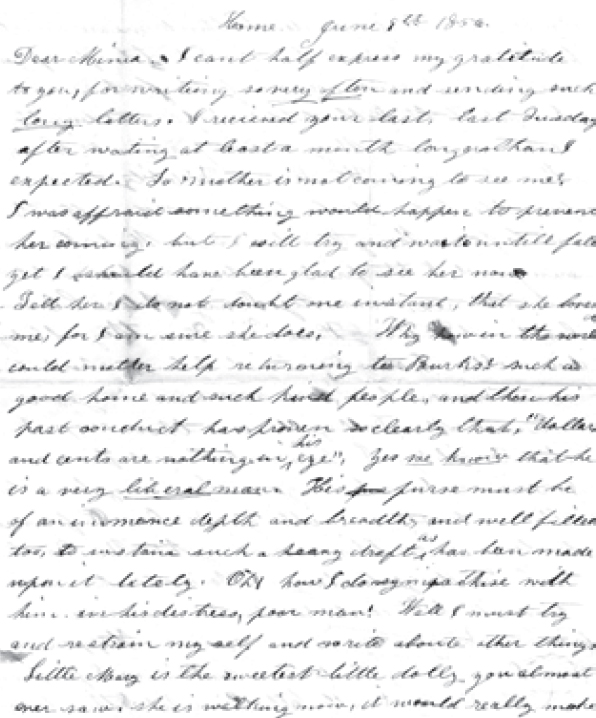

Because of fading of the ink, staining or deterioration of the paper, water damage, or poor handwriting, some words are illegible. We have indicated those by a question mark in brackets. In most cases, we found it possible to discern the author's intent, but we have not supplied the word unless the intent was clear. To make the letters easier to read, we added a bit of punctuation. We have, especially, indicated where sentences begin and end. Punctuation conventions were less clearly settled in the mid-nineteenth century, and the Dumvilles were sparing in their use of periods. We also created some paragraphs. Oddly, some of the earliest letters, written in 185153, use a capital letter on the first word of each line of text (see chapter 2 at ); we have retained that here. In making those decisions, we sought to preserve the character of the letters. On the theory that unconventional spelling may be an important characteristic of a letter, we retained it. Occasionally, where we thought the reader might welcome help, we inserted our interpretation in brackets. We did not alter the style or word choices. The compositions are theirs.

As noted above, some lettersthose we found less informativeare not included here. We also omitted passages that were extraneous, repetitious, fragmentary, or otherwise of little use in telling the story of the Dumvilles. Deletions within letters are indicated by ellipses. Such decisions were, of course, applications of judgment, and other readers of the letters might differ with those judgments. The full collection is in the archives of the Library. Scholars who want to use the letters as primary sources should of course consult the originals.

Some of the letters were written in standard English, or an approximation of it, and others were not. A few appear to be phonetic renditions of nineteenth-century rural dialect. The meaning is usually clear, but some passages are puzzling and may require the reader's creative interpretation. Most of the stylistic differences among the letters are attributable to the differing levels of sophistication of their authors. Some are due to maturationthe daughters letters, for the most part, improved in spelling, grammar, and syntax as they aged. It is also clear, however, that they devoted varying degrees of care and thought to the letters. When they wrote hurriedly, the letters show it.

The Dumvilles were economical in their use of stationery. Paper was expensive. Therefore, they often wrote marginalia, and putting the several pieces together into the intended sequence involves guesswork. Indeed, there may not have been a clearly intended sequence. The paper on which the Dumvilles wrote is lightweight, without any decoration or borders, probably indicating that they chose inexpensive stock. They usually filled the pages on both sides, but rarely used a second sheet. The letter was folded into a small rectangle and the address was then either written on the outside of the sheet, if that was blank, or the page was put into a small envelope. The envelopes, unlike the stationery, were of heavier weight and sometimes had embossed decoration.

Figure 2: A letter written by Hephzibah, 1856. Courtesy of Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum.

With the introduction of postage stamps in 1847,letters that did not use envelopes. Postmarks varied during this period and, much to the disappointment of the historian, often did not include the year. Only the location of the post office, the month, and the day were consistently noted.

For the purpose of presentation and discussion, the letters have been divided into periods chosen to correspond with changes in the content of the letters. The number of letters per year increased from one in 1851 to three in 1852, four in 1853, ten in 1854, and fourteen in 1855. The frequency peaked at fifteen in 1857. The reason for the increase is probably that in the earlier years two of the daughters were located near each other, so it was not necessary for them to communicate by mail. When one of the daughters later returned to her mother's home, the sisters wrote more often.

Where the letters were housed from 1863 until the mid-twentieth century is unclear. By the end of that time, certainly, they were in the possession of descendants of B. T. Burke, the employer of Ann Dumville, the mother. Burke's granddaughter loaned the letters to MacMurray College (the successor to the Methodist's Illinois Conference Female College) in the 1940s for use in the preparation of the college's centennial history,

Ann Dumville lived at the Burke residence in her later years. It is possible that the letters were left behind when she died. Did Ann's daughters travel to her funeral and then deal with her personal effects? Or did Burke handle the disposition of Ann's personal property when she died? Perhaps the Dumville family left the letters with the Burkes, intending to pick them up later (but never did so), or perhaps the letters were simply overlooked and forgotten, by both the Dumvilles and the Burkes. B. T. Burke died in 1876, three years after Ann. There is a considerable collection of Burke family correspondence, and the Dumville letters were in the same boxes with that correspondence as late as the 1990s. Letters from Ann Dumville to B. T. Burke, sent while he was traveling, were among those loaned to MacMurray College by Burke's granddaughter in the 1940s. The photograph of Ann Dumville labeled Grandma Dumville was found with the letters (see in chapter 1).

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.