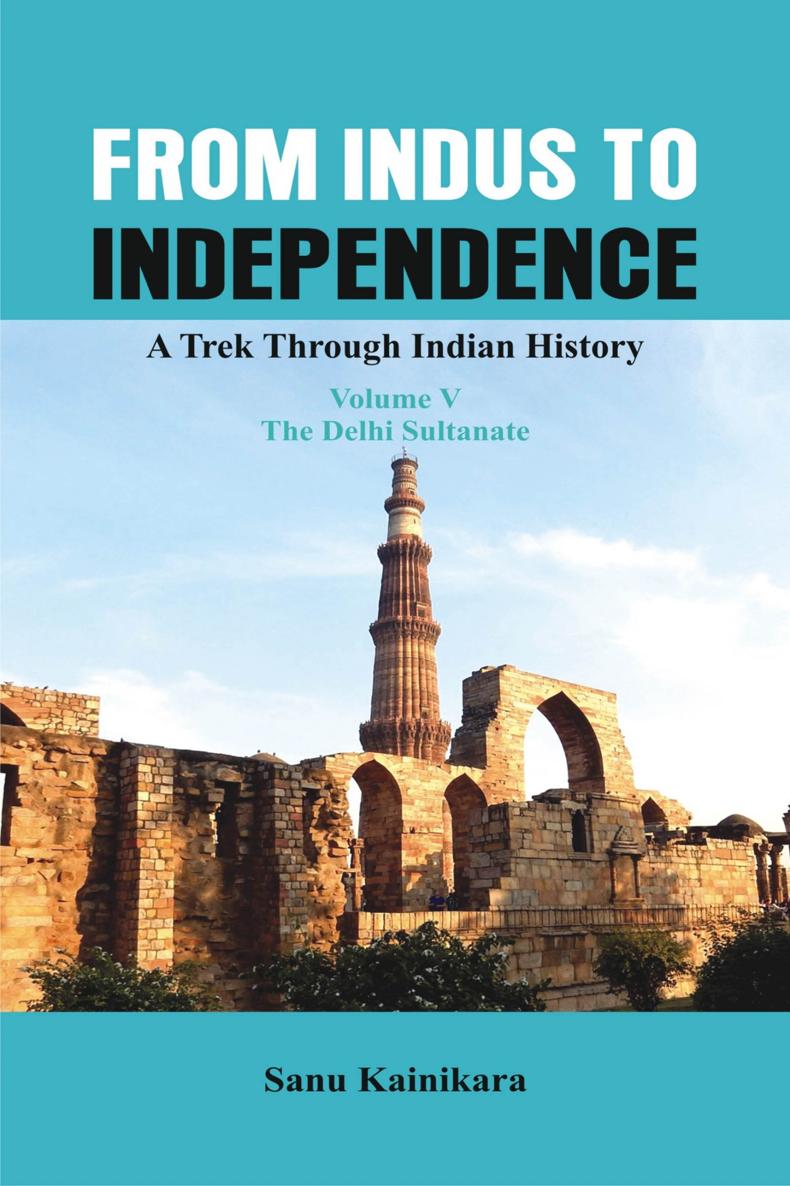

From Indus to Independence

A Trek Through Indian History

From Indus to Independence

A Trek Through Indian History

Volume V

The Delhi Sultanate

Sanu Kainikara

Vij Books India Pvt Ltd

New Delhi (India)

Copyright 2018, Sanu Kainikara

Dr Sanu Kainikara

416, The Ambassador Apartments

2 Grose Street

Deakin, ACT 2600, Australia

First Published in 2018

ISBN : 978-93-86457-71-4 (Hardback)

ISBN : 978-93-86457-73-8 (ebook)

Designed and Setting by

Vij Books India Pvt Ltd

2/19, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi 110002, India

(www.vijbooks.com)

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or utilized

in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise,

without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Application for such permission should

be addressed to the author.

For

Betu

Priya Kainikara-Sharma

A daughter is Gods unmatched gift.

He made it so by creating beauty at its fairest.

You, my daughter, reside deepest in my heart as

a day that smiles through its sunshine;

a night of dew and calm.

You, my daughter, are my soul and breath.

OTHER BOOKS BY SANU KAINIKARA

National Security, Strategy and Air Power

Papers on Air Power

Pathways to Victory

Red Air: Politics in Russian Air Power

Australian Security in the Asian Century

A Fresh Look at Air Power Doctrine

Friends in High Places (Editor)

Seven Perennial Challenges to Air Forces

The Art of Air Power: Sun Tzu Revisited

At the Critical Juncture

Essays on Air Power

The Bolt from the Blue

In the Bears Shadow

Political Analysis

The Asian Crucible

Political Musings: Turmoil in the Middle-East

Political Musings: Asia in the Spotlight

The Indian History Series: From Indus to Independence

Volume I: Prehistory to the Fall of the Mauryas

Volume II: The Classical Age

Volume III: The Disintegration of Empires

Volume IV: The Onslaught of Islam

Challenges to Understanding the Past

T he recounting and analysis of Indian history has become an undertaking fraught with the prospect of the author being maligned by votaries of the Hindu Right, especially if one takes what is perceived as an anti-Hindu stance in the evaluation. The perception of an anti-Hindu slant is often based on a less than clear understanding of the truth of history and the unchanging nature of events that have already passed. In recent times, the term anti-Hindu has become equated to being anti-national and anti-Indian. In these circumstances, the historical analyst often finds himself (herself) on very contentious grounds and must tread carefully in order to be seen, viewed and understood as being scrupulously unbiased.

Historical analysis requires the use of disciplined, yet imaginative and interpretive powers on the part of the analyst. The study must be firmly based on evidence that is not only tangible but also corroborated by other sources. More importantly, it must also be informed by the histories of regions, groups, events and perspectives that have been largely ignored in the broader and more popular history. In the case of India, this quest often leads to a division between pre- and post-colonial rendering of its history. It also divides the post-colonial writings into what are considered narratives in the same mould as that of the colonial era writings and later writings that tend to be more nationalistic in their outlook. In order to avoid the pitfalls associated with both these approachesthe one maintaining the status quo and the other attempting to infuse a sense of national pride through recounting more palatable episodesthe analyst needs to start with a clear idea of what both the approaches would mean. Only then can a new, fresh and clean approach be adopted. Needless to say, achieving such an unbiased approach is a difficult task. A historian is also liable to be indirectly influenced by who he or she is, and his or her own preconceived ideas and beliefs, at the subconscious level. No one is immune to this influence.

The latest fad in India is to work towards discrediting professional historians, since it is perceived that their task is only to fit their writings to pre-given analysis as truths. Liberal left-leaning historians are moving towards explanatory historical recounting rather than providing fact-based interpretive and analytical narratives. The directions that such explanatory histories could take will challenge most of the fundamentals of historic analysis since they would be devoid of any obligation to be based on verifiable facts. In turn, such histories risk the suppression of inconvenient truths and thus could lead to the long-term perpetuation of doctored history. This trend would not only re-write history but glorify a past that perhaps does not merit glorification. Serious students of history should not let this travesty take hold. They must make a concerted attempt at ensuring that history and its analysis remain above narrow political and nationalistic assertions and parochial considerations. Indian history, complex as it is, cannot be permitted to be hi-jacked to cater for political expediency and people with a biased agenda that they, in their ignorance, label as being patriotic and nationalistic. True nationalism is best served by accepting, analysing and learning from the mistakes of the past.

***

There is a myth that was primarily perpetuated by the European colonial historians that ancient and medieval Indians did not have a sense of history and that this trait has continued to influence the modern Indian society. This perception is blatantly incorrect. It has now been established that ancient India had a distinct sense of history that had been developed mainly through the religious texts. These texts provide clear perceptions of the historic development of the Indian entity. Being predominantly based on a religious narrative, the sense of history in the Indian context was developed from a very different perspective in comparison to the Western ideas of history. The Vedic texts, the great epics of Hinduismthe Ramayana and Mahabharata the Puranas, the Buddhist and Jain religious texts, inscriptions on ancient temple structure and even theatrical compositions like the Mudrarakhasa provide the foundations for the recounting of Indian history. These sources are radically different from the sources that Western historical analysts consider acceptable to recount history. The conflict of ideas is obvious.

In medieval times, recorded Indian history was more narrative than analytical and primarily of a complimentary nature. They were written by court chroniclers who were always dependent on the king/sultan for their livelihood and therefore tended to smooth over inconvenient truths regarding the rulers and glossed over his proclivities. Even battlefield defeats were turned at least into indecisive battles if not into partial victories itself, through recounting the events in couched language. During this period history was not viewed in correlation with religious developments but purely as a chronological narrative of events. They did not form part of a collective recollection of the grand pattern of human endeavour that typified the times. At best these narratives could be considered the recording of human acts of volition, omission and commission as well as chronicles of the trials of human nature. Kings and sultans were accordingly labelled strong or weak, liberal or orthodox, tyrannical or broad-minded. Medieval Indian history was only analysed at a much later time, that too by European historians with their own biases against India and Hindus.