Contents

Guide

For my boysMax and Zachary

O ne summer many years ago, I was having a rough Sunday morning. It came after a string of bad days when I struggled with work and relationships, and I was quiet and tense. My eight-year-old son was invited to a birthday party about an hours drive away, and as we left the house, I snatched a slim hardcover book from a pile near the door. Zachary was tired, and he napped on the way, quietly snoring in the back seat, and this was fine by me. When we got to the party, held in the backyard of a grand house in suburban Connecticut, I made small talk with the adults and then slipped away and sat under a tree and took out the book and started to read.

It was The Origin of the Universe, written by John Barrow, a theoretical physicist. It began by describing Edwin Hubbles discovery that the universe was expanding, and then went over the evidence for the Big Bang theory of how everything started.

As I read, my heart began to beat faster. It was so exciting that we could know about all this, that I could be reading about events that happened fourteen billion years ago. Perhaps its what people of faith feel like when reading Scripturethe experience of great truths being revealed. Learning about the universe, I felt insignificant, tiny in space and time. But I also felt proud of our speciesthat we could know so much about the incredibly long ago and incredibly far away, that we could make real progress on the most fundamental of all questions. And when the birthday party was over and I got up to get my son, the world was full of light.

Driving back, I talked to Zachary about what I learned, and as we spoke, I played with the fantasy of quitting my job as professor of psychology, getting a new degree, and becoming a cosmologist. But I was where I belonged. The tombstone of the philosopher Immanuel Kant has a quote from his Critique of Pure Reason: Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the more often and more steadily we reflect upon them: the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me. I had spent the morning being thrilled by the starry heavens; years later my research would turn to morality and moral psychology, and there again I would experience the same admiration and awe as Kant.

Honestly, though, just about all of psychology gives me this buzz. Its about the most interesting topic there isus. Its about our feelings, experiences, plans, goals, fantasies, the most intimate aspects of our being.

The book you are holding is built from an Introduction to Psychology course that Ive taught for many years as a professor at Yale University. This is one of the most popular courses at Yale, and I have taught thousands of undergraduates, sometimes as their very first course at a university. Based on these lectures, I created an online course that has had an enrollment, so far, of about a million students.

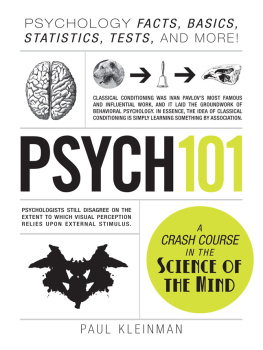

I love teaching Introduction to Psychology. But there is a limit to how much one can convey in a series of lectures, and there is so much material to cover. And so I decided to write Psych. The scope here is broad, and if you choose to read this from cover to cover, youll have a grounding in every major aspect of the science of psychology. Among other things, Psych will put forth the best answers we have to the following questions:

How does the braina three-pound lump of bloody meatgive rise to intelligence and conscious experience?

What did Freud get right about human nature?

What did Skinner get right about human nature?

Where does knowledge come from?

How does the mind of a child differ from that of an adult?

What is the relationship between language and thought?

How do our biases affect how we see and remember the world?

Are we rational beings?

What motivates usand what is the purpose of feelings such as fear, disgust, and compassion?

How do we think of other peopleincluding those from other social and ethnic groups?

How (and why) do we differ in personality, intelligence, and other traits?

What is the cause and treatment of different mental illnesses?

What makes people happy?

Each chapter of this book can be read as a stand-alone piece. Its fine if you decide to dive in and read about Freud, or language, or mental illness. Or even jump to the end, to the part on happiness. Nobody is judging you. But there is a flow to this book; there are themes and ideas that stretch across these disparate chapters, and there is a satisfaction to seeing the story unfold in its proper order.

Some parts of this story make people uncomfortable. Well see that modern psychology accepts a mechanistic conception of mental life, one that is materialist (seeing the mind as a physical thing), evolutionary (seeing our psychologies as the product of biological evolution, shaped to a large extent by natural selection), and causal (seeing our thoughts and actions as the product of the forces of genes, culture, and individual experience).

You might worry that there is something missing here. This conception of mental life might seem to clash with commonsense notions of free choice and moral responsibility. It might seem to clash as well with the notion that humans have a transcendent or spiritual nature. The tension here is nicely illustrated by John Updike in his Rabbit at Rest, when Harry Rabbit Angstrom talks to his friend Charlie about Charlies recent surgery:

Pig valves. Rabbit tries to hide his revulsion. Was it terrible? They split your chest open and ran your blood through a machine?

Piece of cake. Youre knocked out cold. Whats wrong with running your blood through a machine? What else you think you are, champ?

A God-made one-of-a-kind with an immortal soul breathed in. A vehicle of grace. A battlefield of good and evil. An apprentice angel...

Youre just a soft machine, Charlie maintains.

There are different ways to react to all this. I know philosophers and psychologists who confidently assert theres no such thing as free will or moral responsibility. And Ive met others who reject the science, who worry that such an approach to the mind takes the specialness away from people, it diminishes us somehow. Its too reductionist, too crude. It reduces us to computers or lumps of cells or lab rats. They reason: If psychology is going to tell me that Im just a machine, that the most intimate aspects of my being are nothing more than neural firings, well, so much for psychology.

My own view is that we can find a middle ground here. I think the scientific perspective at the core of modern psychology is fully compatible with the existence of choice and morality and responsibility. Yes, we are, in the end, soft machinesbut not just soft machines.

I want to end this prologue with a note of humility. We know so much about the physical world and so little about mental life. This isnt because physicists are smart and psychologists are stupid. Its because my chosen domain of study is so much harder than Barrows. The mysteries of space and time turn out to be easier for our minds to grasp than those of consciousness and choice. In the pages that follow, Ill be honest about the limitations of our young science and critical of some colleagues who think weve solved it all.

But theres a real joy to being part of a young science. I find the study of psychology to be just as exhilarating as this study of the cosmos, and I hope you come to see it this way as well. We have made exciting progress in the field and I cant wait to talk about it. My fondest hope for this book is that the theories and discoveries reviewed here will give rise to a sort of awe in the reader, something akin to what I experienced when I read about the origins of the universe under that tree many years ago.