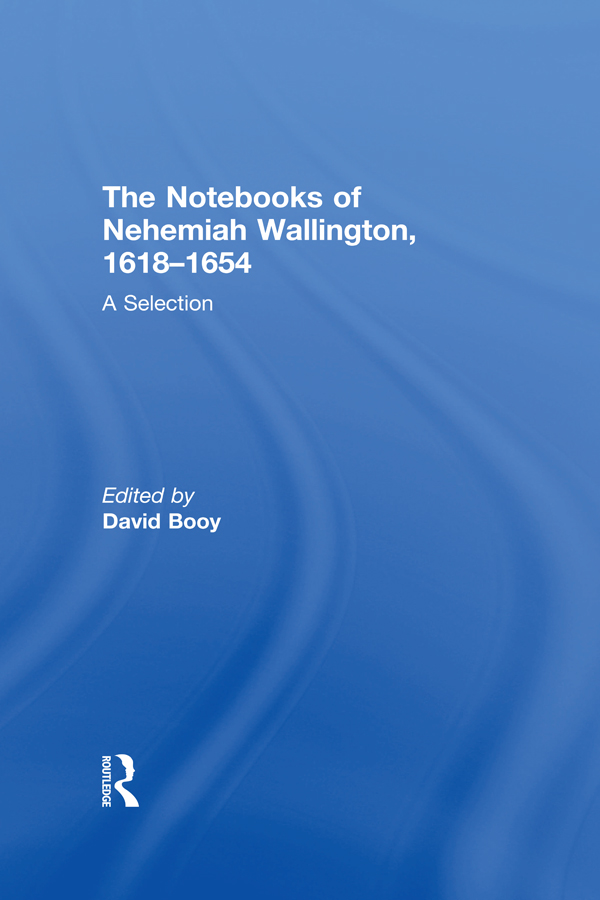

The Notebooks of Nehemiah Wallington, 16181654

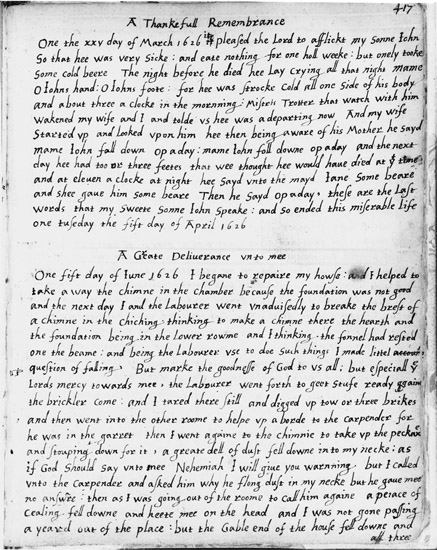

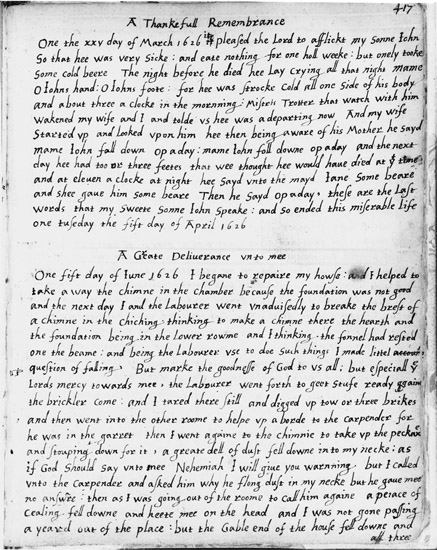

An extract from A Record of Gods Marcys (Guildhall Library MS 204, p. 417). Reproduced by permission of the Guildhall Library, City of London

First published 2007 by Ashgate Publishing

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2007 David Booy

David Booy has asserted his moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Wallington, Nehemiah

The notebooks of Nehemiah Wallington, 16181654 : a selection

1. Puritan movements England Early works to 1800

2. Dissenters, Religious England Early works to 1800

I. Title II. Booy, David

285.9092

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wallington, Nehemiah.

The notebooks of Nehemiah Wallington, 16181654 : a selection / [edited by]

David Booy.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7546-5186-4 (hardback : alk. paper)

1. Wallington, Nehemiah. 2. London (England)Social life and customs17th

century. 3. London (England)History17th centuryBiography. 4. Puritans

EnglandBiography. 5. ArtisansEnglandBiography. I. Booy, David. II. Title.

BX9339.W26A3 2007

285.9092dc22

[B]

2006018848

ISBN 9780754651864 (hbk)

For Ann

Contents

(Guildhall Library, London, Manuscript 204)

(British Library, Sloane Manuscript 1457)

(British Library, Additional Manuscript 21 935)

(British Library, Additional Manuscript 40 883)

(Tatton Park Manuscript 68.20)

(British Library, Sloane Manuscript 922)

(Folger Shakespeare Library Manuscript V.a.436)

For historians of the early modern period, the puritan woodturner, Nehemiah Wallington, is a well-known figure, whose notebooks are regularly referred to in the discussion of many topics: religion, politics, the Civil Wars, events in London, medicine, suicide, family life, book-buying, sexual desire and its repression the list could be extended. It is therefore surprising that there is no modern edition of Wallingtons writings. A few scholars consult the original notebooks, some quote from Webbs rather unsatisfactory 1869 edition of one of them, and many cite them via Paul Seavers monograph, Wallingtons World (1985), which quotes extensively from the notebooks. It was Seavers fine study that brought the London artisan to a much wider readership and that inspired me to undertake this edition of Wallingtons writings. My work is indebted to Seaver in numerous ways, and his book is essential reading alongside this one.

Of the 50 notebooks Wallington compiled, only seven are known to have survived. Given that these contain over 3200 pages, a complete edition of his extant writings is currently impracticable. Moreover, for most people, I suspect, such an edition would make for tiresome reading: the notebooks contain a good deal of repetition, not just of themes but of actual material, and further, even for someone with a deep interest in spiritual matters and the history of religion, Wallingtons prolonged and often repetitive meditations, prayers and reflections become wearisome. These features of the notebooks also dissuaded me from producing an edition of a single manuscript. I believe the best way to bring Wallingtons writings to a wider audience is through a judicious selection of material from all the extant notebooks that demonstrates their full range and character.

This book is therefore an anthology of Wallingtons writings. However, I have guarded against presenting snippets from the notebooks, but have in the main provided substantial continuous or near continuous excerpts. Given that this is a selection, though, it cannot fully satisfy everyone. As Wallington himself remarked when considering what to include in a compilation from earlier notebooks, it is unpossible to writ to everyons likeing for wee diffur in our judgments for that which likes one disliks another (Folger Shakespeare Library Manuscript V.a.435, p. xi).

I have aimed to illustrate the variety of topics covered in the notebooks, and have not just opted for material likely to have an immediate appeal for a modern reader (for example, acounts of domestic mishaps, City fires, or popular demonstrations at Westminster). It would have misrepresented the notebooks entirely if I had not included enough writing to demonstrate Wallingtons relentless, obsessive preoccupation with religious matters and particularly with his own spiritual state. It is crucial to register that his demanding beliefs dominated his life in every way and caused him much anguish as well as fortifying him and occasionally bringing him joy. In any case, his sustained self-examination for religious purposes is fascinating, and his diaries offer an unrivalled opportunity to encounter the interior spiritual life of an ordinary puritan layman in the first half of the seventeenth century in England.

Although this edition illustrates the diversity of Wallingtons output, my primary concern is with the notebooks as life-writings or self-writings, and thus my chief aim is to present material that gives insight into Wallingtons personal life, thoughts and attitudes: overt autobiographical narrative, letters, reflections on his spiritual state and his own responses to events in his private and public worlds. Interest in early-modern autobiographical texts has grown considerably in the past 15 years or so, stimulated particularly by the bid to recover womens history. More recently, scholars have begun to examine such writings by male authors from the period. In this context too, a selection from Wallingtons notebooks is timely, and I trust will make a useful contribution to the study of early-modern lives and their written expression.

The extent of my selection has of course been determined by the word-limit for this book, which has meant excluding much material I should have preferred to keep. Wallington copied out a great many passages from books, newsbooks, pamphlets, sermons, letters and the Bible, and these were obvious candidates for exclusion on the grounds that, pressed for space, it was better for me to present Wallingtons own words. On the other hand, his copying reveals a lot about his cast of mind, interests, and reading and writing habits; indeed, as Tom Webster (1996: 36) says, collecting and recording the words of others is a form of ego-literature. This has led me to include a number of items Wallington transcribed from elsewhere.