PLAGUES, POISONS

AND POTIONS

SOCIAL AND CULTURAL VALUES IN EARLY MODERN EUROPE

Series editor

Paolo L. Rossi

Department of Italian Studies

University of Lancaster

In its exploration of the cultural and social upheavals in early modern Europe, this series crosses traditional disciplinary boundaries. It offers a broad-ranging analysis of the forces which shaped structures of belief and practice at all levels of society, providing original insights into the mentality of early modern Europeans.

The volumes assess the manner in which central as well as peripheral values, institutions and disciplines evolved and, through this identification of metamorphoses, seeks to redefine the mechanics of change and to re-evaluate the meanings of a central or hegemonic culture.

Individual titles address many neglected or emerging subject areas, incorporating the history of the less studied countries of Eastern Europe. In so doing, the contributors examine a vast range of source material, including literary, historical, scientific, philosophical and artistic evidence.

Other titles in the series:

Astrology and the seventeenth-century mind

Ann Geneva

Healers and healing in early modern Italy

David Gentilcore

Devoted people: belief and religion in early modern Ireland

Raymond Gillespie

Martin del Rio: investigations into magic

Peter Maxwell-Stuart

Copyright William G. Naphy 2002

The right of William G. Naphy to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Altrincham Street, Manchester Ml 7JA, UK

http://www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for

ISBN 0 7190 4640 8 hardback

0 7190 4641 6paperback

First published 2002

10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

List of tables

Series editors foreword

Acknowledgements

List of abbreviations

Maps

Introduction

One Geneva, plague and the first conspiracy

Two The magistrates and plague, 154246

Three The conspirators of 1545

Four The magistrates and plague, 156772

Five The conspirators of 1571

Six Spreading the phenomenon

Conclusion

Appendices

One Households infected with plague, 154246

Two Genevan medical practictioners, 153646

Three Accused engraisseurs, 154346

Four Magisterial participation, 154546 trials

Five Individuals accused of witchcraft, 154346

Six Genevas plague workers, 161415

Seven Milans plague spreaders: the witnesses

Bibliography

Index

Defence witnesses, Genet case, 1530

Prosecution witnesses, Genet case, 1530

Magistrates participation in the trials of 1530

Sequence of trials, February-March 1545

Sequence of trials, AprilOctober 1545

Sequence of trials, 1546

Sequence of trials, 1568

Sequence of trials, 1569

Plague spreaders in 1570

Sequence of trials, JanuaryMarch 1571

Sequence of trials, JuneDecember 1571

Milans plague spreaders: the accused

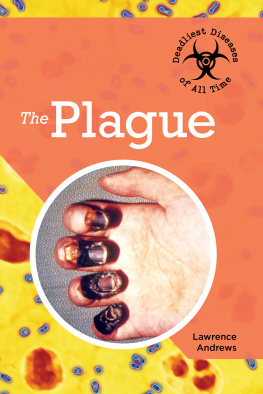

The Black Death of 1347, though a calamitous epidemic, was but one of the many outbreaks of plague to hit Europe since the pandemic of the sixth century A.D1 Plague struck down its victims without regard to wealth or social status. A bacterial infection caused by the Yersinia pestis bacillus, the plague attacked in three forms bubonic, septicaemic, and pneumonic.2 It is difficult for us to imagine the fear and panic that must have spread through town and country at the news of a fresh outbreak. Plague originated in the East (where it is still endemic) and can be transmitted by the rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis), and the human flea (Pulex irritans). If a person suffering from bubonic plague also develops pneumonic plague then the bacillus can be passed by spittle or mucus. Septicaemic and pneumonic plague are particularly lethal and can cause death within the day.

We have only become aware of the true cause of bubonic plague since the 1890s. Early theories saw causes in: astral conjunctions; the passing of comets; unusual weather conditions; miasmas caused by a great explosion in the East that could affect the humours; noxious exhalations from the corpses on battlefields; person- to-person contact linked to the movement of people such as merchants, travellers and beggars; contact with infected merchandise.3 Plague was associated with sin, and accepted as a manifestation of divine ire. It was also linked to the poor (the plague was even seen by some as Natures way of controlling their numbers), and measures were put in place to oversee their movements, and to isolate them in times of pestilence.4

Given the mistaken aetiology it is hardly surprising that the precautions taken were not fully effective. At times remedies increased rather than prevented infection. For instance the killing of cats and dogs only allowed the population of rats to increase. The towns of northern Italy, where Public Health Boards were established, led the way in the battle to control the plague. Initially these were set up ad hoc in response to particular outbreaks, but eventually, due to the frequent recurrence of plague, they became permanent committees. Measures against the plague included: evacuation of plague sufferers (usually the poor) to huts; the setting up of plague hospitals; the hiring of doctors to cope with the numbers of the sick, and of cleaners for infected houses; disinfection, fumigation, and the burning of infected clothing and bedding; quarantine of those who had come into contact with victims (richer citizens were allowed to remain shut up in their own homes); the restriction of movement at borders, and the hiring of night-watchmen to control incoming goods and travellers; forbidding citizens who had visited places of plague to enter the city under pain of death.5 People also sought salvation in wondrous medicines such as theriac, and other concoctions which belong to the mystical world of alchemy with such names as pulvis imperialis, domina medicinarum, manus Dei, oculus Christi, nobilissima medicina, a morte liberans.6

The link between plague and the gods in Homer was echoed in Christian beliefs. These connected plague to Evil, and thereby to the activities of the Devils followers. The Malleus Maleficarum stated that the category of witches that can injure, but not cure, is the most powerful category, and these can cause all the plagues which other witches can only cause in part, when the justice of God permits such things.7 The mechanism for plague spreading was to make up powders, or an unguent containing an infectious substance(s). Nicolas Rmy wrote in 1545, Since it is not convenient for them [witches] to keep this powder ready in their hand to throw, they have also wands imbued with it or smeared with some unguent or other venomous matter.8 Rmy makes a distinction between plague spreading by witches which was person specific, and plague spreading by others which was indiscriminate. The ointment did not affect everyone but only those whom the witch wishes to injure, whereas others who spread the plague strike those whom you least wish to harm.9 According to Rmy the witch can only effect her poison due to the hidden ministry of the Demon, which does not appear but works in secret.10 Rmy makes an important distinction, between demon aided and non-demon aided plague-spreading.11 Deliberate plague-spreading seems to have been widespread and entered into folk memory. Manzoni, when discussing the plague of Milan in the