First published as Sunnites et Chiites: Histoire politique dune discorde originally published ditions du Seuil and is copyright 2017 by ditions du Seuil. The English translation by Ethan Rundell is copyright 2020 by Princeton University Press.

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lour, Laurence, author. | Rundell, Ethan S., translator.

Title: Sunnis and Shia : a political history of discord / Laurence Lour; translated by Ethan Rundell.

Other titles: Sunnites et Chiites. English

Identifiers: LCCN 2019027366 (print) | LCCN 201902 (ebook) | ISBN 9780691186610 (hardcover)

eISBN 9780691199641

Subjects: LCSH: ShahRelationsSunnites. | SunnitesRelationsShah. | IslamDoctrines. | Islam and politics.

Classification: LCC BP194.16 .L6813 2020 (print) | LCC BP194.16 (ebook) | DDC 297.8/042dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019027366

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019027367

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Fred Appel and Jenny Tan

Production Editorial: Debbie Tegarden

Text Design: Leslie Flis

Jacket/Cover Design: Layla Mac Rory

INTRODUCTION

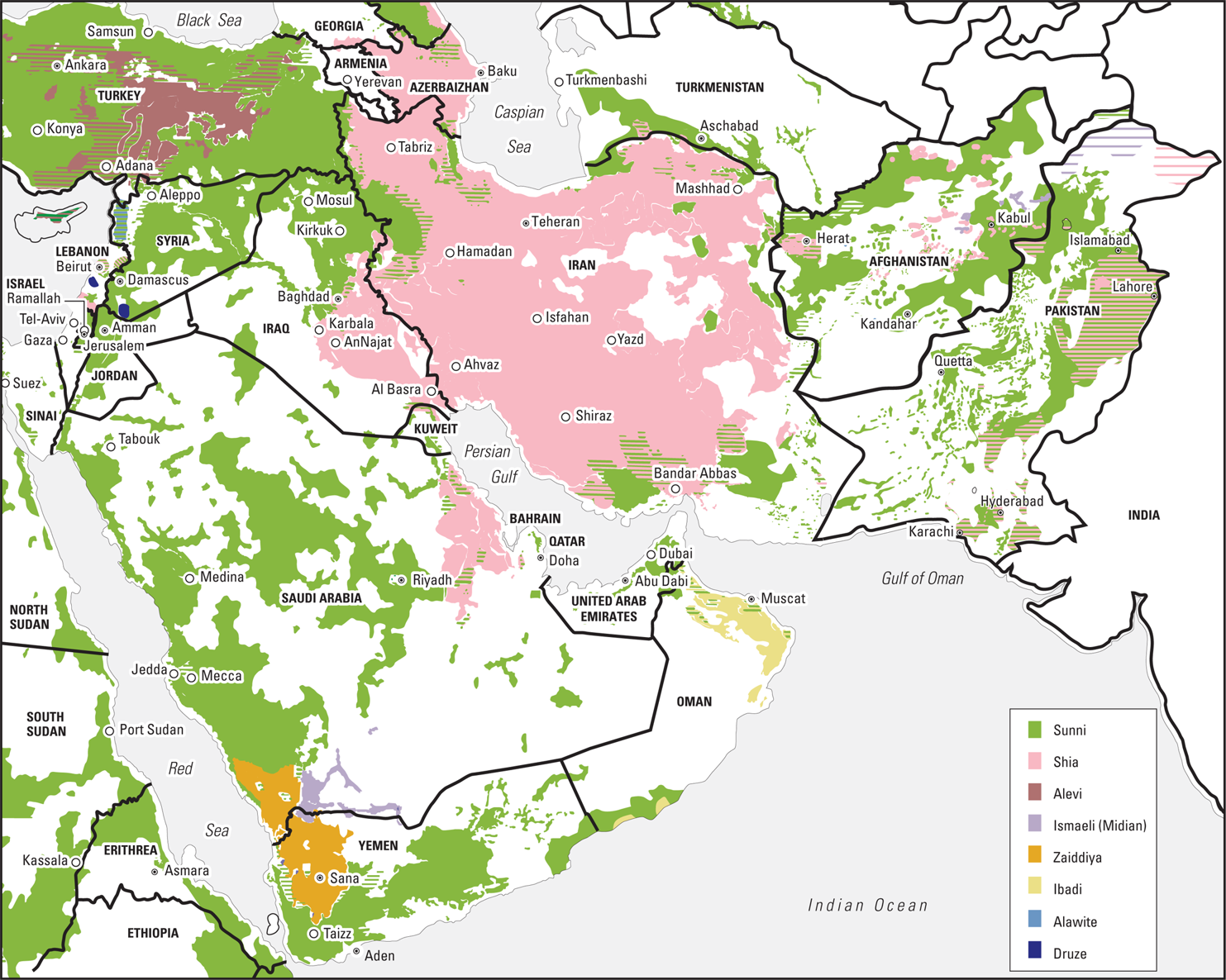

Relations between Sunni and Shii Muslims are often said to be characterized by over a thousand years of uninterrupted war, the result of ancestral hatreds stemming from disagreements over the Prophet Muhammads rightful successor. According to Sunnis, who today probably constitute as much as 90 percent of the worlds Muslim population, Muhammad left no instructions as to who should succeed him when he died without a male heir in 632, leaving it up to his companions to determine who would best govern. By contrast, the Shia believe that Muhammad, directly inspired by God, designated his cousin and son-in-law Ali ibn Abi Talib as his successor. The latter would become the fourth caliph, and Shia hold that a lineage of Imams was born of his marriage with the Prophets daughter, Fatima.

Yet the conflict between Sunnis and Shia was never just a mere quarrel over the prophet of Islams succession. For it immediately raised essential questions as to the nature of legitimate political authority. What sort of qualities should be possessed by the Muslim head of state? Could he be an ordinary human being or should there be something of the divine about him? How was he to be chosen and, by extension, what was the most legitimate type of political regime?

Such were the questions raised by the protagonists of the time. They were ever on the mind of future generations, giving rise to political and religious doctrines as well as myths that continue to structure Sunni and Shii political imaginaries to this day. For Sunnis and especially Islamists, the rightly guided caliphate of Muhammads first four successors represents a golden age of just government to which one must return. For the Shia, by contrast, the first three caliphs were no more than usurpers. In fighting unjust authority, the heroes of our time must in their eyes strive to emulate Hussein, the son of Imam Ali, who was killed by the army of Caliph Yazid in 680.

Over the centuries, these controversies were activated or deactivated depending on the political context. This is the central argument of the present book. Religious doctrines thus generally evolved in response to the political needs of dominant and dominated groups. They served as legitimating ideologies for political elites; rebels used them to oppose the powers that be; clerics wielded them to assert themselves vis--vis state power. In the course of these interactions, Sunnis and Shia were not always in open conflict. While Shiism in its various manifestations has long been the principal ideology of opposition to the established powers of the Middle East, the Twelver movement that today predominates gradually took shape around a project of doctrinal and political deradicalization that resulted in marginalizing the esoteric and revolutionary currents that were so central during the first centuries of Islam. Orchestrated by Shii religious scholars, this process made it possible to conceive of peaceful coexistence with the established powers and also established Shiism as a school of religious law that, in point of its conclusions, ultimately differed little from the canonical Sunni schools.

When the Safavids in 1501 moved to establish Shiism as the state religion over a territory roughly corresponding to that of contemporary Iran, however, the conflict was reactivated. By making what had been a communal religion into an official religion and using it as a tool for wielding influence beyond their frontiers, the Safavids created a lasting fault line in the Middle East, with the Sunni-Shia divide being superimposed in the collective imagination on a conflict between Iran and the rest of the Muslim world. This fault line still exists today: for many Sunnis, every Shia is necessarily Iranian or at least an agent in the service of Irans expansionist intrigues. Many of the conflicts that are today tearing the region apart center on the conflictual relationship between Saudi Arabia and Iran, the two states claiming to embody and champion Sunni and Shia Islamism, respectively. Their rivalry intersects with and internationalizes what are at the outset independent local conflicts, introduces religious issues into political struggles, and hardens fluid denominational identities.

To understand the dynamics by which the conflicts between Sunnis and Shia are activated and deactivated, the present work takes a twofold approach. In the first offer a global political history of Sunnis and Shia from the beginning of the quarrel over succession until today. In doing so, I seek to explain the historical roots of contemporary conflicts, underscore historical continuities and ruptures, and cast light on dynamics of antagonism and points of convergence.

The second part offers an at once historical and sociological study of several national configurations in which the Sunni-Shia divide structures the political field. This brings to the fore the manner in which Sunni and Shia identities are articulated with other social, ethnic, linguistic, regional, economic, and status identities. It is this articulation, specific to each society, that explains why, though present in many Middle Eastern countries, the Sunni-Shia divide does or does not develop into more or less violent conflicts depending on the domestic and regional political contexts.