Routledge Revivals

Rastaman

First published in 1979, this book makes a detailed study of Rastafarianism. It traces the expansion of Rastafarian culture from its origins and development in Jamaica through to the growth of Rastafarian life in Britain. It looks at Rastafarian culture in England in the late 1970s based on the authors intimate experiences and communications with followers of the movement.

Rastaman

The Rastafarian Movement in England

E. Cashmore

First published in 1979

by George Allen & Unwin Ltd

This edition first published in 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1979 E. Cashmore

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

A Library of Congress record exists under ISBN: 79040684

ISBN 13: 978-0-415-81261-0 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-203-06869-4 (ebk)

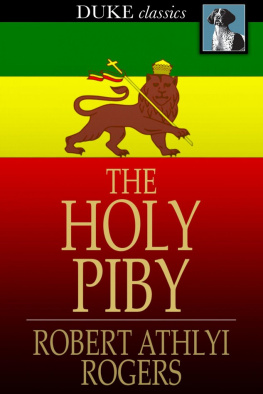

At this moment methinks I see Ethiopia stretching forth her hands unto God and methinks I see the Angel of God taking up the standard of the Red, the Black and the Green, and saying, Men of the Negro Race, Men of Ethiopia, follow me. Climb ye the heights of liberty and cease not in well doing until you have planted the banner of the Red, the Black and the Green on the hilltops of Africa.

Marcus Garvey (Philosophy and Opinions, Vol. 1, 1967)

And I saw a strong angel proclaiming with a great voice. Who is worthy to open the book, and to loose the seven seals thereof? And no one in heaven, or on earth, or under the earth, was able to open the book, or to look thereon: and one of the elders saith to me, Weep not: behold, the Lion that is of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, hath overcome, to open the book and the seven seals thereof.

Revelation, 5:1-6

Were sick and tired of your easing kissing game

to die and go to heaven in Jesus name

we know and understand

almighty God is a living man

Bob Marley and Peter Tosh (Get Up, Stand Up, 1973)

I became fascinated by the Rastafarian movement when a graduate student at the University of Toronto. Having noticed isolated groups of these somewhat bizarre-looking characters and heard of their uneasy relationship with the Toronto Metropolitan Police, I was intrigued to come across an article in Rolling Stone magazine which dealt with the contemporary movement in Jamaica (Michael Thomas, 1976).

In 1976 I left Canada to take up a position as a research student at the London School of Economics and had the chance to stop off at Jamaica en route. Here I took the opportunity to talk to locals and make observations on the movement. I found myself absorbed by their beliefs and lifestyle. On arrival in England I became very aware that the movements relevance was not merely confined to Jamaica and Toronto, but to Birmingham, London and other urban areas of England. I had noticed the existence of tams (woolly hats) and peculiar hairstyles of black youths before leaving for Canada (in 1975) and was familiar with Dick Hebdiges then unpublished paper, Reggae, Rastas and Rudies (1975), but the movements growth in my absence was astonishing and I considered it worthy of serious attention.

Accordingly, I approached my supervisor, Professor Percy Cohen, with the idea of an empirical study to explore the origins, development and present state of the Rastafarian movement in England and, after a few false starts, the work got under way in November 1976.

My initial approaches were daunting, for the Rastas had recently suffered the embarrassment of being labelled a mafia organisation (by the Reading Evening Post) and were to suffer similar brandings in the months that followed. Complicating the issue further was the fact that its members regarded the movement as exclusive and not amenable to outsiders; for a white investigator like myself, I was informed it makes no sense. On occasions I met with disinterest and even refusals to talk to me. Apart from chance encounters and casual conversations with individuals, I made little sustained contact. All the time I was piecing together the history of the movement and gaining what I later found out to be insight.

The turning point came when Father M. Charles, an Anglican vicar, introduced me to members of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church in Birmingham to whom he loaned his church for services. I am indebted to these brothers for their co-operation and, indeed, encouragement. Armed with even deeper insight after reasoning at length with church members, I grew in confidence and was able to reason more effectively with other groups not affiliated to the church.

From here the situation snowballed, as well as attending the church, I frequented several Rastafarian haunts and engaged in protracted reasoning sessions (Rasta discourses); my reputation as a man of insight grew and I gained what I felt to be acceptance. Having seen me in conversation with Rastas, other members had their initial doubts or fears assuaged and their suspicion or hostility dissolved, thus paving the way for open communication.

Periodic obstacles hindered the research: the publication of Browns Shades of Grey in late 1977 aroused alarm about the nature of outsiders studying the movement and I came under scrutiny; my participation in the production of London Weekend Televisions Credo programme on the Rastas incurred the wrath of a great many, particularly those I had recruited for the interviews. Thankfully, I was able to convince them of my purity of intention and motivation and by the time of the works completion (winter, 1978) my relationships were sounder and more amiable than ever.

To single out individuals from the hundreds of Rastas with whom I reasoned is an exercise to which Rastas themselves would object. I would, however, express a special thanks to Brothers Kinfe Gabriel and Claudius Haughton of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, Birmingham, Ras Anthony Elliott of the Twelve Tribes of Israel, London, and Brother Dennis Deans for their unstinting co-operation in the provision of insight.

I would also like to acknowledge some intellectual debts. First, impersonal ones to Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann whose book The Social Construction of Reality (1972) was inspirational to the whole exercise; but also to Bryan Wilson and Michael Barkun for their respective works Magic and the Millennium (1973) and Disaster and the Millennium (1974) both of which were treasure houses of concepts and themes; from these I have stolen many gems. Less visible, but still influential, was Roy Walliss The Road to Total Freedom (1977). The chapter on Reality Maintenance in a Deviant Belief System was a direct spur to my .

On a more personal level I would like to thank Professor Abner Cohen of the School of Oriental and African Studies for reading and commenting on drafts of . I owe a particular debt of gratitude to my supervisor Percy Cohen who read through earlier drafts of the whole work and provided comment and criticism. His personal encouragement and support for the enterprise were indispensable assets.