Perspectives on Kentuckys Past

ARCHITECTURE, ARCHAEOLOGY, AND LANDSCAPE

Julie Riesenweber

General Editor

The

Synagogues

of

Kentucky

Architecture and History

Lee Shai Weissbach

Copyright 1995 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN: 978-0-8131-3368-3 (pbk. : alk. paper)

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of

American University Presses |

For Cobi and Maya

Contents

Maps

Sponsors Foreword

KENTUCKYS THOUSANDS OF CULTURAL resources form a tangible record of twelve thousand years of history and prehistory. They include archaeological sites such as native American villages and burial mounds, the historic remains of fortifications of our first European settlers, and Civil War earthworks and battlefields. Above ground are structures ranging from individual houses to entire streetscapes of Victorian commercial buildings. These resources combine to form a past and present environmenta cultural landscapeworthy of preservation.

Preservationists have always made decisions about which cultural resources should remain for future generations, but these decisions are becoming even more difficult. No longer is preservation a simple matter of saving old buildings from the wrecking ball or restoring them to their original appearance. Preservationists today must not only consider a more comprehensive and diverse array of properties, but also attempt to unravel the complex relationships among them. One way the profession responds to challenges posed by the rapidly changing times is to seek better understanding of the cultural resources with which it is concerned.

The Kentucky Heritage Council, the State Historic Preservation Office, encourages the study of the Commonwealths architecture, archaeology, and landscape. As a growing number of constituents demand that decisions be weighed in light of many special interests, preservation increasingly becomes a public endeavor. The preservation profession must find ways of communicating the information gained through scholarly research so that the public is aware of the relationships and meanings behind practical decisions. Publication of the series Perspectives on Kentuckys Past is among the Kentucky Heritage Councils ongoing educational efforts.

Cultural diversity has become a major theme in many endeavors, including historic preservation. Where historical scholarship used to focus on rich and powerful white men, it now seeks information about working people, women and ethnic minorities in the past. Likewise, while early preservation efforts involved the restoration of masterworks of architecture and the stylish homes of prominent citizens, they now concern buildings, neighborhoods, communities and landscapes that were commonplace in the past and illustrate the diversity of American culture.

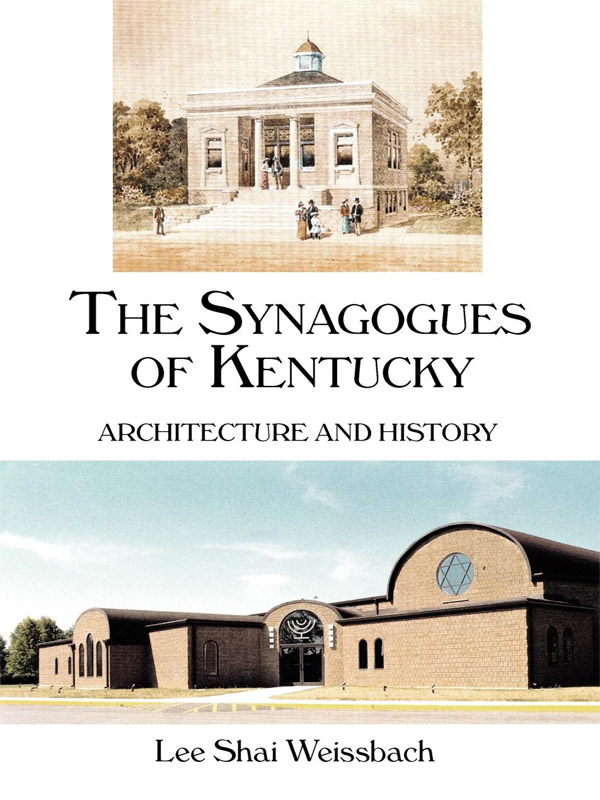

For this reason I am especially pleased that the second volume in the Perspectives on Kentuckys Past series presents information about an ethnic group not typically thought of in connection with Kentucky. The Synagogues of Kentucky is the first comprehensive survey of Kentuckys Jewish communities and synagogues. In this pioneering study of small Jewish communities outside the major American urban centers, Lee Shai Weissbach has employed demographic, architectural, and archival data and combined the disciplines of religious, social, and architectural history. He shows that synagogues, as the centers of Jewish religious and community life, have both influenced and reflected the evolution and identity of Jewish communal life in Kentucky, and he thus gives us persuasive reasons for their preservation.

David L. Morgan, Director

Kentucky Heritage Council and

State Historic Preservation Officer

Acknowledgments

IN PREPARING THIS VOLUME I have relied on the help of many individuals. Some made practical suggestions; others shared information and advice in correspondence or in conversation; still others assisted with the technical aspects of my project. I thank them all and offer my genuine apologies to anyone whose help I received but whom I have inadvertently failed to recognize here. It goes without saying, of course, that any faults to be found in this book are my responsibility alone.

My research could not have been accomplished without access to a great many primary sources, and at each and every one of the libraries and archives that I used (they are enumerated in my essay on methodology and bibliography), I found staff members who were extremely gracious and cooperative. Special mention in this regard is due to Kevin Proffitt of the American Jewish Archives in Cincinnati. Although I do not know by name all the other librarians and archivists who facilitated my research, I want to express my gratitude to them as a group.

Within each of the individual Kentucky communities I studied, I encountered many individuals who were willing and even eager to help me. For sharing their knowledge of the Louisville Jewish community and of their own congregations, I thank Herman Landau, the author of Adath Louisville; Milton Russman of the Israel T. Naamani Library located at Louisvilles Jewish Community Center; Mary Wolf, one of the founders of the new Adat Bnai Yisrael congregation; Rabbi Chester Diamond of The Temple, and Jack Benjamin, The Temples administrator. I also thank Richard Wolf, co-chair of the original building committee for The Temple; Rabbis Avrohom Litvin and Solomon Roodman of Congregation Anshei Sfard; Rabbi Shmuel Mann of Congregation Keneseth Israel; Rabbi Robert Slosberg of Adath Jeshurun; and Ernie Marks, that congregations ritual director. I am indebted as well to the late Rabbi Simcha Kling of Adath Jeshurun, a native of the Newport Jewish community who became a highly revered communal leader and spiritual presence in Louisville; I regret that he did not live to see this volume completed.

Also deserving of my thanks are Louisville architects Gerald Baron, John P. Chovan, and Robert A. Nolan, Sr., each of whom spent time talking to me about his work on Kentuckys synagogues. I am grateful too for the aid and encouragement I received from Samuel W. Thomas, author of several books on Louisvilles architectural environment, and from Joanne Weeter, my principal contact at the Louisville Landmarks Commission.