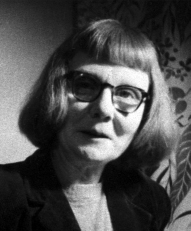

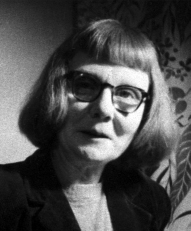

CARYLL HOUSELANDER (1901-1954) was a lay English artist who became one of the most popular Catholic spiritual writers of modern times.

Baptized Catholic as a schoolgirl, she was sickly and misunderstood by her athletic, popular parents who had little interest in religion. Caryll and her sister were tutored by an agnostic lawyer and later sent to a Catholic boarding school when their parents divorced. As a young adult, Caryll returned to the Church with a passionate intensity and fresh insights.

Though a woodcarver and art therapist for children, her true gift was sharing a unique and mystical vision of Christianity and Catholic teachings through her writing. In the 1940s and into the 1950s, she wrote prolifically. Her first major book, This War Is the Passion, was published in 1941. In 1944, The Reed of God, a collection of profound and lyrical essays about Mary, established Houselander as a respected modern spiritual writer in the tradition of Julian of Norwich, Catherine of Siena and Teresa of Avila.

Her contributions to spiritual literature were cut short by an early death at fifty-three from cancer.

EMPTINESS

THAT virginal quality which, for want of a better word, I call emptiness is the beginning of this contemplation.

It is not a formless emptiness, a void without meaning; on the contrary it has a shape, a form given to it by the purpose for which it is intended.

It is emptiness like the hollow in the reed, the narrow riftless emptiness, which can have only one destiny: to receive the piper's breath and to utter the song that is in his heart.

It is emptiness like the hollow in the cup, shaped to receive water or wine.

It is emptiness like that of the bird's nest, built in a round warm ring to receive the little bird.

The pre-Advent emptiness of Our Lady's purposeful virginity was indeed like those three things.

She was a reed through which the Eternal Love was to be piped as a shepherd's song.

She was the flowerlike chalice into which the purest water of humanity was to be poured, mingled with wine, changed to the crimson blood of love, and lifted up in sacrifice.

She was the warm nest rounded to the shape of humanity to receive the Divine Little Bird.

Emptiness is a very common complaint in our days, not the purposeful emptiness of the virginal heart and mind but a void, meaningless, unhappy condition.

Strangely enough, those who complain the loudest of the emptiness of their lives are usually people whose lives are overcrowded, filled with trivial details, plans, desires, ambitions, unsatisfied cravings for passing pleasures, doubts, anxieties and fears; and these sometimes further overlaid with exhausting pleasures which are an attempt, and always a futile attempt, to forget how pointless such people's lives are. Those who complain in these circumstances of the emptiness of their lives are usually afraid to allow space or silence or pause in their lives. They dread space, for they want material things crowded together, so that there will always be something to lean on for support. They dread silence, because they do not want to hear their own pulses beating out the seconds of their life, and to know that each beat is another knock on the door of death. Death seems to them to be only the final void, the darkest, loneliest emptiness.

They have no sense of being related to any abiding beauty, to any indestructible life: they are afraid to be alone with their unrelated hearts.

Such emptiness is very different from that still, shadow-less ring of light round which our being is circled, making a shape which in itself is an absolute promise of fulfilment.

The question which most people will ask is: Can someone whose life is already cluttered up with trivial things get back to this virginal emptiness?

Of course he can; if a bird's nest has been filled with broken glass and rubbish, it can be emptied.

It is not only trivialities which destroy this virgin-mindedness; very often, serious people with a conscious purpose in life destroy it by being too set on this purpose. The core of emptiness is not filled by trifles but by a hard block, tightly wedged in. They have a plan, for example, for reconstructing Europe, for reforming education, for converting the world; and this plan, this enthusiasm, has become so important in their minds that there is neither room to receive God nor silence to hear His voice, even though He comes as light and little as a Communion wafer and speaks as soft as a zephyr of wind tapping on the window with a flower.

Zealots and triflers and all besides who have crowded the emptiness out of their minds and the silence out of their souls can restore it. At least, they can allow God to restore it and ask Him to do so.

The whole process of contemplation through imitation of Our Lady can be gone through, in the first place, with just that simple purpose of regaining the virgin-mind, and as we go on in the attempt we shall find that over and over again there is a new emptying process; it is a thing which has to be done in contemplation as often as the earth has to be sifted and the field ploughed for seed.

At the beginning it will be necessary for each individual to discard deliberately all the trifling unnecessary things in his life, all the hard blocks and congestions; not necessarily to discard all his interests forever, but at least once to stop still, and having prayed for courage, to visualise himself without all the extras, escapes, and interests other than Love in his life: to see ourselves as if we had just come from God's hand and had gathered nothing to ourselves yet, to discover just what shape is the virginal emptiness of our own being, and of what material we are made.

We need to be reminded that every second of our survival does really mean that we are new from God's fingers, so that it requires no more than the miracle which we never notice to restore to us our virgin-heart at any moment we like to choose.

Our own effort will consist in sifting and sorting out everything that is not essential and that fills up space and silence in us and in discovering what sort of shape this emptiness in us, is. From this we shall learn what sort of purpose God has for us. In what way are we to fulfil the work of giving Christ life in us?

Are we reed pipes? Is He waiting to live lyrically through us?

Are we chalices? Does He ask to be sacrificed in us?

Are we nests? Does He desire of us a warm, sweet abiding in domestic life at home?

These are only some of the possible forms of virginity; each person may find some quite different form, his own secret.

I mention those three because they are all fulfilled in Our Lady, so visibly that we may be sure that we can look at them in her and learn what she reveals through them.

It is the purpose for which something is made that decides the material which is used.

The chalice is made of pure gold because it must contain the Blood of Christ.

The bird's nest is made of scraps of soft down, leaves and feathers and twigs, because it must be a strong warm home for the young birds.

When human creatures make things, their instinct is to use not only the material that is most suitable from the point of view of utility but also the material most fitting to express the conception of the object they have in mind.

It is possible to make a candle with very little wax and a lot of fat, but a candle made from pure wax is more useful and more fitting; the Church insists that the candles on the Altar be made of pure wax, the wax of the soft, dark bees. It is beautiful, natural material; it reminds us of the days of warm sun, the droning of the bees, the summer in flower. The tender ivory colour has its own unique beauty and a kind of affinity with the whiteness of linen and of unleavened bread. In every way it is fitting material to bear a light, and by light it is made yet more lovely.

Next page