The Apocryphile Press

1700 Shattuck Ave. #81

Berkeley, CA 94709

www.apocryphile.org

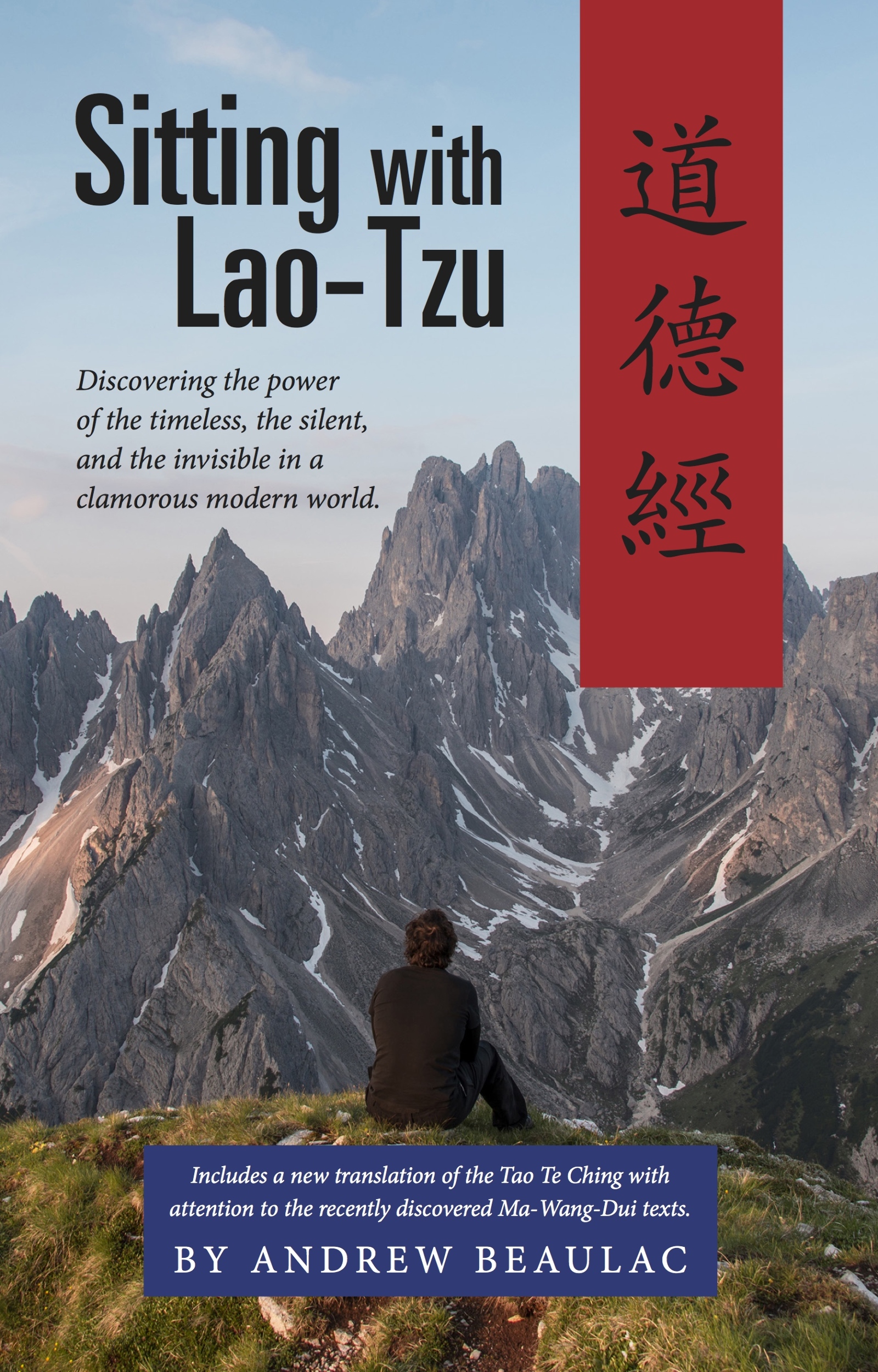

Sitting with Lao Tzu

Copyright 2016 Andrew Beaulac

ISBN 978-1-944769-41-3

eISBN 978-1-944769-60-4 (Kindle)

eISBN 978-1-944769-61-1 (ePub)

Ebook version 2

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America

Dedication

For Philip and Lindsay

We might call this world the forms of the Formless,

the shapes of what has no substance.

It is described as obscure and elusive.

Seeking to encounter it there is nowhere to begin,

and to follow it there is nowhere we must go.

Just hold fast to the timeless Way

in order to manage what is present now,

and thus penetrate the ancient origin.

This present moment is the continuing thread of the Universal Way.

LAO-TZU

Acknowledgments

I t is with deep gratitude that I thank Red Pine for his generosity of time and expertise in helping me work through questions about the translation, for reading the essays and making helpful comments, and for his encouragement to go on with the work and seek publication. My heartfelt thanks to Sarah Cassatt for always having a ready ear and interested mind when I went on about the Tao and Lao-tzu, and for reading through the manuscript with a careful eye and listing so many helpful suggestions, all of which I have followed. I thank Mark Ambrose for countless long phone discussions about the Tao as we enjoyed solving the worlds problems with its timeless wisdom, regardless of whether the world would listen. Finally, I thank Pat Sullivan for proofreading with such a careful eye, finding so many typos and errors to which I had become snow-blind from looking at the manuscript for too long. Any remaining errors are, of course, no ones responsibility but my own.

Contents

Chapter 1:

Chapter 2:

Chapter 3:

Chapter 4:

Chapter 5:

Chapter 6:

Chapter 7:

Chapter 8:

About the Translation

M any venerable translations began in the nineteenth century, when Chinese was rendered into English under the Wade-Giles system of Romanization. This has been carried on for works from Chinese antiquity, and you see it in the terms Tao Te Ching, Lao-tzu, Chuang-tzu, and others. I took the advice of the publisher in retaining Lao-tzu and Tao-Te-Ching for the books title because of their name-recognition; interested people are looking for those words. Within the book, however, I have chosen to render Chinese terms with the current Pinyin Romanization because 1) it has been the international standard since 1982, and 2) its suggested pronunciations are a little less bizarre than many from the Wade-Giles system. For clarification, I usually follow the first Pinyin transliteration of a Chinese term with the Wade-Giles version in parentheses. For example: Laozi (Lao-tzu), or ziran (tzu-jan). Though neither system provides a perfect pronunciation of the Chinese, ziran is much closer than tzu-jan!

Because of the many differences in various translations, I wanted to understand what Chinese words and concepts lay behind such varied translations. I had begun unpacking the Laozi book using the Wang Pi and Ho-shang Kung commentaries provided by Alan K.L. Chan. In addition, I scrutinized a word-by-word Chinese text listing many possible definitions for each character, and various grammatical and interpretive notes. Also, I relied heavily on Red Pines wonderful work which includes indispensable commentaries by Chinese Daoists from the last two-thousand years. Even giving the text due diligence, I nevertheless needed some sound guidance for certain parts, and verification that my understanding of Daoist thought as expressed in the essays was reasonably accurate.

Some years ago, it was my good fortune and great pleasure to sit with Red Pine, one of the foremost translators of old Chinese Daoist and Buddhist texts. He happened to live within traveling distance and, more importantly, he was so generous with his time that he invited me to his home to work through problematic parts of the Chinese texts. He also read through my preliminary essays and made helpful suggestions. My deepest thanks to this kind and generous scholar.

More often than not, being accurate and literal with a Chinese text and making it communicate well in English are mutually exclusive options, and I was vacillating endlessly between the two. What I wanted to do was translate the heart-mind of the Laozi text for the modern western mind, which is so very different. Many times an accurate word-for-word literal translation of the text will leave a western reader shrugging with indifference or incomprehension. Over cups of the best Oolong tea I have ever tasted, Red Pine told me the most important thing for my work, which, as I remember it, was basically: Translation is like a dance; if you and Laozi are hearing the same melody, you will be dancing in unison even if you are on the other side of the room from each other. You dont need to stand on Laozis toes in your translation. I was immediately released from a wooden, word-for-word translation.

The purpose of this book is not to provide yet another translation of this profound text. The Dao De Jing is already the second or third most translated book in the world! I own fifteen different English translations. Why create another? For Sitting with Lao-tzu, I might have chosen one to quote with permission, but my favorite renderings of various verses were from too many contrasting translations. I had to get at the Chinese text behind them all, and see what is actually there. Then various principles of analysis and interpretation were employed which led to a fresh translation.

Such a long and intricate journey is its own reward. So, even though this translation began as incidental to the essays, it has become essential: I feel it gives a number of obscure passages a clarity lacking in many translations and helps bridge the heart of Laozi to the modern western mind. I hope readers will discover in it a faithful conveyance of the Laozis mind behind the words.

The Dao is what is subtly underlying all creation. As such, it is prior to, and quite beyond, all words and descriptions. But it is also treated as a life-path, a Way. In most verses I leave it untranslated, as Dao, but not always. Anytime you see the capitalized Way, it is a translation of the same word: Dao.

The essays are preparatory to the translation, because they explain important words and concepts the reader will encounter. Nevertheless, I feel that ones initial exposure should be to Laozi first, and so begin with the translation of the eighty-one verses. Readers are encouraged to approach this book in whichever order they prefer. Within the translation also, some verses are given explanations of textual interpretive choices, cultural context, or thoughts for meditative reflection.

When I first encountered Laozi, I was stunned by how contrary it is to almost everything I had been conditioned to think and feel. Later, I was amused by how honest, natural and obvious it is. Sitting with Laozi yourself, your mind may become quiet as you discover a timeless consciousness. One of Laozis successors, Zhuangzi (or Chuang-tzu), describes the journey thus: