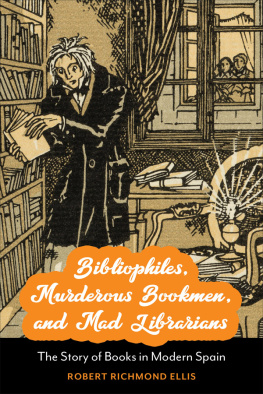

Bibliophiles, Murderous Bookmen, and Mad Librarians :The Story of Books in Modern Spain

University of Toronto Press 2022

Toronto Buffalo London

utorontopress.com

Printed in the U.S.A.

ISBN 978-1-4875-4236-8 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-4875-4238-2 (EPUB)

ISBN 978-1-4875-4237-5 (PDF)

Toronto Iberic

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Bibliophiles, murderous bookmen, and mad librarians : the story of books

in modern Spain / Robert Richmond Ellis.

Names: Ellis, Robert Richmond, author.

Series: Toronto Iberic ; 67.

Description: Series statement: Toronto Iberic series ; 67 | Includes bibliographical

references and index.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20210346620 | Canadiana (ebook) 20210346752 |

ISBN 9781487542368 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781487542382 (EPUB) |

ISBN 9781487542375 (PDF)

Subjects: LCSH: Books in literature. | LCSH: Books and reading in literature. |

LCSH: Book collecting in literature. | LCSH: Bibliomania. | LCSH: Book

collecting Spain. | LCSH: Spanish literature 19th century History and

criticism. | LCSH: Spanish literature 20th century History and criticism. |

LCSH: Spain Intellectual life.

Classification: LCC PQ6072 .E45 2022 | DDC 860.9/39dc23

We wish to acknowledge the land on which the University of Toronto Press operates. This land is the traditional territory of the Wendat, the Anishnaabeg, the Haudenosaunee, the Mtis, and the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation.

This book has been published with the assistance of Occidental College and the Brown Humanities Book Publication Fund.

University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial support of the Government of Canada, the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Ontario Arts Council, an agency of the Government of Ontario, for its publishing activities.

In memory of my mother, grandmother, and grandfather, and to Jos Horacio, as always

Qu jardn de abril, qu Aranjuez del mayo como una librera selecta?

[What April garden, what Aranjuez of the month of May, can match a select library?]

Baltasar Gracin, El Criticn

Contents

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

There are many people and institutions whose support over the years has helped make this book possible.

I am particularly grateful to Occidental College for helping fund my research in the Biblioteca Nacional de Espaa and the Biblioteca de Catalunya through a MacArthur International Grant, and for generously providing financial assistance for the publication of the book. I am also grateful to my colleagues in the Department of Spanish and French Studies for their steadfast support and good cheer over the years.

I want to thank my primary editor at the University of Toronto Press, Mark Thompson, for his judicious guidance throughout the editorial process, and all the people at the Press for helping bring the project to fruition. I am also deeply appreciative of the wisdom and good advice of the readers of the manuscript.

Bibliophiles, Murderous Bookmen, and Mad Librarians :The Story of Books in Modern Spain

Introduction

The most famous depiction of books in all of Spanish literature is a scene in Miguel de Cervantess Don Quixote in which the title characters library is destroyed. Don Quixote is a voracious reader whose passion for the tales of knight-errantry has supposedly led him to madness, and for this reason his niece, housekeeper, barber, and local curate decide that his library must be burned. Just prior to the book burning, the curate examines the library and expresses a keen interest in the importance and quality of many of the volumes. In so doing, he reveals the temperament of a bibliophile, even if he is the person most responsible for the obliteration of what in his day would have been a large and valuable collection. Don Quixote, although beside himself with anger when he discovers that his treasured books have vanished, ultimately blames the incident on the machinations of an evil enchanter a figure that originally entered his imagination through reading. He thus regards his books (and, by extension, the entire world) through the lens of the discourses that he has encountered in them. The episode is nevertheless paradigmatic in the history of the Spanish book. Not only does it affirm both a love of reading and an appreciation of the aesthetic appeal of physical books, but it also, in the context of the seventeenth-century Inquisition, exposes the threat posed to books by forces of oppression, and even suggests that their destruction is tantamount to the destruction of human life itself. What is more, it captures the almost wild despair felt by those who lose books, when in the wake of the crime Don Quixote lashes out in a blind and hopeless rage. Yet through his imagination, Don Quixote does retain much of what he has lost, just as Cervantes, through his narrative, gives renewed life to the voices and stories of the past.

The great themes expressed in Don Quixote regarding books and bibliophilia are present throughout the history of Spanish book culture, and feature prominently in Spanish book-centred narratives of subsequent centuries. My aim in the work that follows is precisely to examine how books are represented in modern Spanish writing, both literally and metaphorically, and how modern Spanish commentators of books reflect on the role of books in their lives and in the cultural life of modern Spain. The overarching subject of my study is bibliophilia, a love of books both as texts to be read and objects to be cherished for their physical qualities. Like their counterparts in other countries, Spanish bibliophiles have painstakingly described the characteristics of books, the book arts, libraries, and bookshops, and have attempted to explain the psychological experiences of reading and collecting books, as well as the social and economic conditions of book production. They have also used images of books to tell a multitude of stories. Whereas some of these stories highlight the diverse histories, politics, and nationalisms of the modern Spanish state, others engage in a more philosophical meditation on such topics as personal identity, the nostalgia for the past, the nature of good and evil, and mortality and immortality.

Spanish bibliophilia precedes the advent of printing in the West in the fifteenth century, but it flourishes in the ensuing centuries of print culture, culminating in the mid-nineteenth century when the central state confiscated large monastic libraries and either transferred them to public institutions or sold them. The entry of vast numbers of old books into the marketplace, coupled with the beginning of the mass production of new books made possible by the Industrial Revolution, led to what might be called a Golden Age of Spanish bibliophilia, a period spanning the second half of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century. This high point of print culture lasted until other forms of media, including radio, film, and television, gained ascendency and began to augment, if not in some instances replace, print media. In the late twentieth century, with the advent of digital technology, non-print media has become the dominant form of communication, to the point that some commentators of book culture believe that physical books will one day disappear. Yet even though writers such as Enrique Vila-Matas suggest that we are reaching what he calls el fin de la era Gutenberg (

Next page