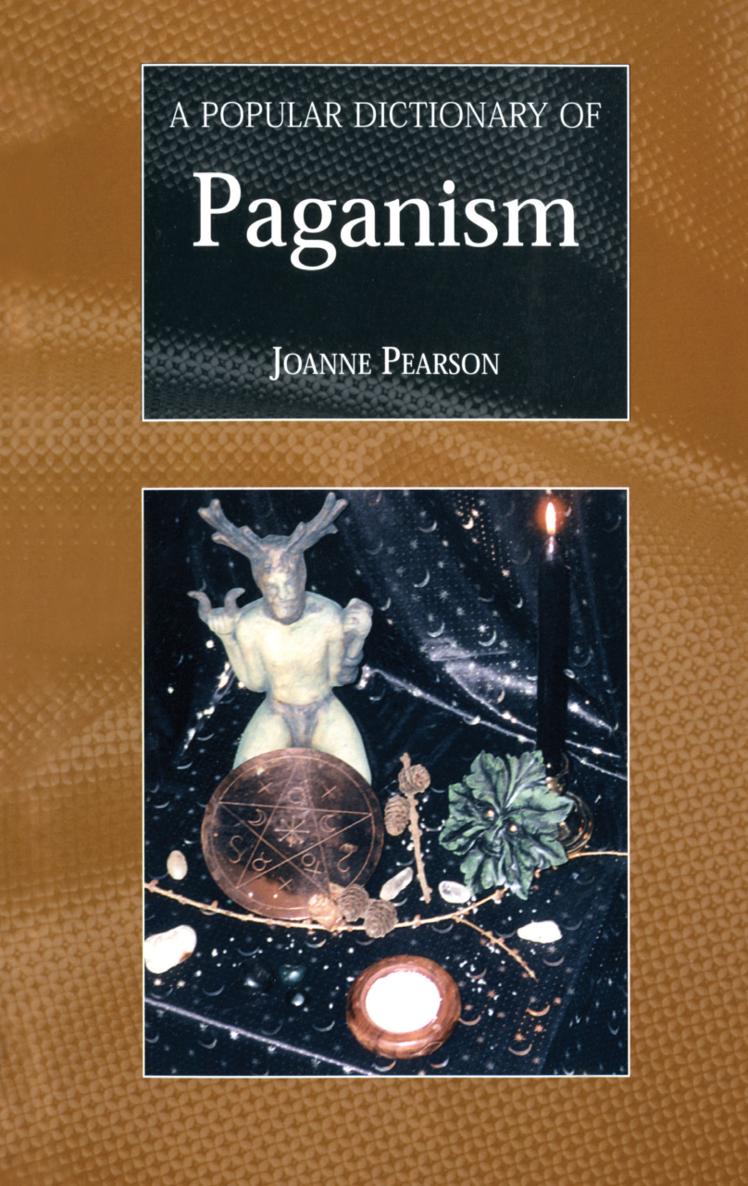

First published 2002 by RoutledgeCurzon

This edition published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge in an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2002 Joanne Pearson

Typeset in Times by LaserScript Ltd, Mitcham, Surrey

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book has been requested

ISBN 070071619X (Hbk)

ISBN 0700715916 (Pbk)

In compiling this dictionary I was helped greatly by many academic colleagues and Pagan friends, who found the time to help out with problems and to point me in the right direction in search of resources and references. Special thanks are due to Professor Ronald Hutton of Bristol University, who kindly allowed me to read his entries on Gerald Gardner and Alex Sanders for the Dictionary of National Biography prior to publication, and has provided a wealth of information and encouragement over the years. Professor Geoffrey Samuel of the University of Newcastle, New South Wales, kindly read and commented on entries related to Hindu tantra, for which I am exceptionally grateful. Marion Bowman, Vivianne Crowley, Jez Green, Graham Harvey, Dominic Montserrat, Robert Poole, and Kate Ward must also be mentioned for their willingness to share information, point out factual inaccuracy, and read entries. Any remaining errors are, of course, entirely my responsibility.

I am, as always, indebted to Nick Freeman, for his careful reading of drafts of this dictionary, valuable comments and suggestions, and encouragement. Without his stoicism in the face of a study strewn with papers and books for months on end, this book would not have materialised!

Paganism is an extremely complex phenomenon, arguably not one religion, or Paganism, but many Paganisms, a coalition which is bound together through significant common ground but which at the same time rejoices both in its contemporary diversity and in the tangles of its historical skein. Even in its modern setting, Paganism has no known or uncontested starting point and no single founder or originator; rather, it has developed into its present forms from a variety of sources which are themselves traceable through the mythic landscape of European history. But the boundaries cannot be set so easily, for Paganism has also drawn upon concepts indigenous to religions outside Europe (adopting chakras from India, for example) and the very word Pagan continues to be an arena of contested meaning.

In contemporary scholarship, Pagan is a term used to describe a variety of contemporary traditions and practices which revere nature as sacred, ensouled or alive, draw on pagan religions of the past, use ritual and myth creatively, share a seasonal cycle of festivals, and tend to be polytheistic, pantheistic and/or duotheistic rather than monotheistic, at least to the extent of accepting the divine as both male and female and thus including both gods and goddesses in their pantheons. It includes a variety of traditions of witchcraft, Pagan Druidry, Asatr/Heathenism, Pagan shamanism, non-aligned Paganism, some forms of Goddess spirituality, and initiatory Wicca. In a very real sense, then, the term describes a religiosity which embraces a range of different religions, rather than a specific religion. This is in keeping with a generally-held Pagan view that no one belief system is correct, and that each person has the freedom to choose their own religion. As such there are no official doctrines and no central authority. Controversial issues within Paganism thus remain unresolved, and the resulting inconsistencies and conflicts tend to be regarded as both constructive and destructive: whilst some demand that all Pagans take up eco-activism, for instance, others maintain a more laissez-faire attitude which expects each individual to practice their form of Paganism according to their own deeply held convictions. The forum for discussions of pertinent issues tends to be the pages of journals and magazines devoted to a Pagan readership, such as the journal of the Pagan Federation, Pagan Dawn. The Pagan Federation, the largest umbrella organisation for Paganism in Europe, has set out three principles which it asks members to adhere to:

Love for and kinship with nature: rather than the more customary attitude of aggression and domination over Nature; reverence for the life force and its ever-renewing cycles of life and death.

The Pagan Ethic: Do what thou wilt, but harm none. This is a positive morality, not a list of thou-shalt-nots. Each individual is responsible for discovering his or her own true nature and developing it fully, in harmony with the outer world.

The concept of the Goddess and God as expressions of the Divine reality; an active participation in the cosmic dance of the Goddess and God, female and male, rather than suppression of either the female or the male principle.

(The Pagan Federation 1992 p. 4)

Such principles purposefully allow for a wide range of interpretation, and require the individual to seek out for themselves the ethical codes by which they live.

Such a description of Paganism leads one to draw the conclusion that there are many Paganisms indeed, that there are as many Paganisms as there are Pagans! However, although there are Pagans who operate in a solitary capacity, Paganism is for the most part a sociable form of spirituality which attracts people who wish to join together in groups. These groups take many forms, from Wiccan covens to Druid groves, from Heathen hearths to magical lodges, and entry into them may be by formal rituals of initiation, dedication to a particular deity or deities, or simply through friendship. Some groups may extol the efficacy of operative magic, deeming it to be a requisite part of Paganism, whilst others eschew magic and follow instead a path of different inclination. But there is common ground as well. Apart from the brief definition provided above, the vast majority of Pagans involve themselves in rituals, the most well-known and extensively celebrated of which are the eight seasonal festivals which together constitute the mythic-ritual cycle known as The Wheel of the Year. These festivals are the so-called Celtic fire festivals or cross quarter days of Imbolc/Candlemas (c. February 2nd), Beltane (c. April 30th), Lughnasadh/Lammas (c. July 31st), and Samhain/Halloween (c. October 31st), plus the Winter and Summer Solstices (December c. 21st and June c. 21st) and the Spring and Autumn equinoxes (March c. 21st and September c. 21st).1 Rites of passage for the birth of a new child, menarche, manhood, marriage, menopause, ageing and death are becoming more popular, and of course there are also initiation rituals and those which celebrate the phases of the moon. Inspiration for these rituals, and the authenticity required to legitimate them, is drawn from the ancient past discovered through archaeology, classics, myth and history, for Pagan religions tend to trace their roots back to the traditions of ancient paganism, reviving and recreating their practices and beliefs in the context of modern-day life. Indeed, the word Pagan itself has been part of this reconstruction.