THE SAMUEL AND ALTHEA STROUM LECTURES IN JEWISH STUDIES

The Yiddish Art Song, performed by Leon Lishner, basso, and Lazar Weiner, piano (stereophonic record album)

The Holocaust in Historical Perspective

Yehuda Bauer

Zakhor: Jewish History and Jewish Memory

Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi

Jewish Mysticism and Jewish Ethics

Joseph Dan

The Invention of Hebrew Prose:Modern Fiction and the Language of Realism

Robert Alter

Recent Archaeological Discoveries and Biblical Research

William G. Dever

Jewish Identity in the Modern World

Michael A. Meyer

I. L. Peretz and the Making of Modern Jewish Culture

Ruth R. Wisse

The Kiss of God: Spiritual and Mystical Death in Judaism

Michael Fishbane

Gender and Assimilation in Modern Jewish History: The Roles and Representation of Women

Paula E. Hyman

Portrait of American Jews: The Last Half of the 20th Century

Samuel C. Heilman

Judaism and Hellenism in Antiquity: Conflict or Confluence?

Lee I. Levine

Imagining Russian Jewry: Memory, History, Identity

Steven J. Zipperstein

Popular Culture and the Shaping ofHolocaust Memory in America

Alan Mintz

Studying the Jewish Future

Calvin Goldscheider

Autobiographical Jews: Essays in Jewish Self-Fashioning

Michael Stanislawski

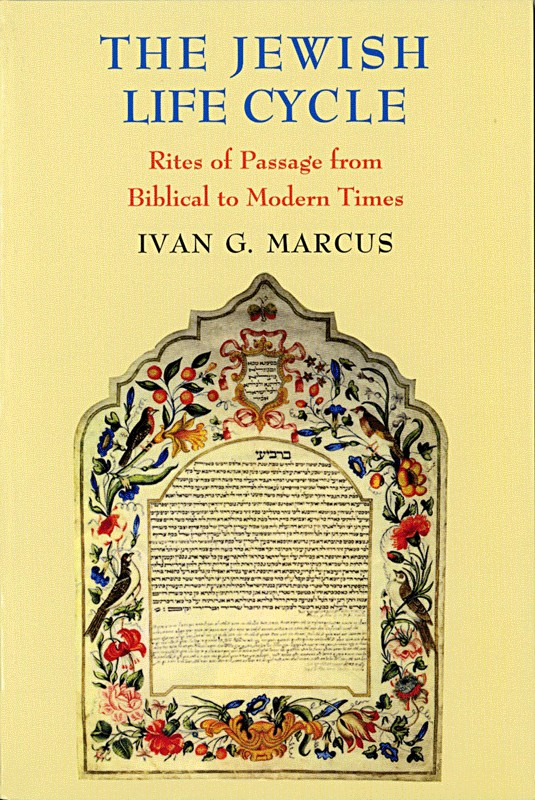

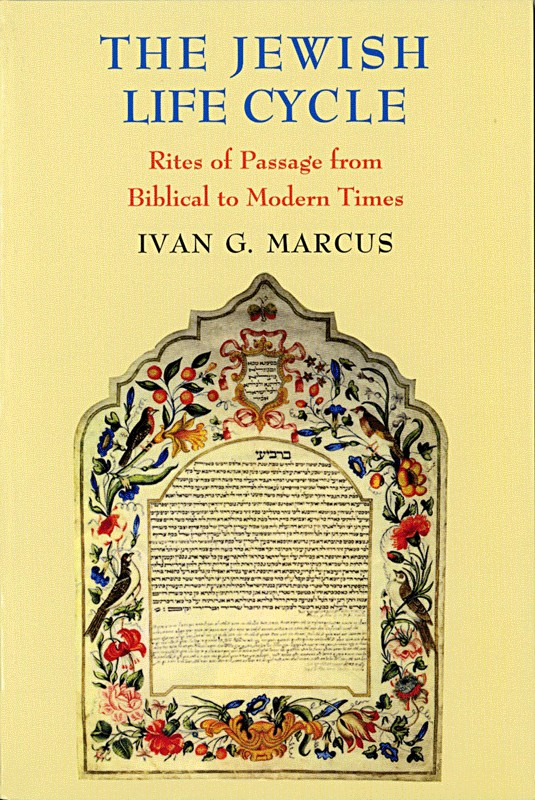

The Jewish Life Cycle:Rites of Passage from Biblical to Modern Times

Ivan G. Marcus

THE JEWISH LIFE CYCLE

Rites of Passage from Biblical to Modern Times

IVAN G. MARCUS

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

Seattle and London

2004 by the University of Washington Press

Printed in the United States of America

Designed by Pamela Canell

12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

University of Washington Press, PO Box 50096, Seattle, WA 98145 www.washington.edu/uwpress

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Marcus, Ivan G.

The Jewish life cycle : rites of passage from biblical to modern times / Ivan G. Marcus.

p. cm. (The Samuel and Althea Stroum lectures in Jewish studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-295-98440-6 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 0-295-98441-4 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. JudaismCustoms and practices. 2. Life-cycle, HumanReligious aspectsJudaism. I. Title. II. Series.

BM700.M27 2004 296.4'4dc22 2004053599

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and recycled from 20 percent post-consumer and at least 50 percent pre-consumer waste. It meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

ISBN 978-0-295-80392-0 (ebook)

THE SAMUEL AND ALTHEA STROUM LECTURES IN JEWISH STUDIES

Samuel Stroum, businessman, community leader, and philanthropist, by a major gift to the Jewish Federation of Greater Seattle, established the Samuel and Althea Stroum Philanthropic Fund.

In recognition of Mr. and Mrs. Stroums deep interest in Jewish history and culture, the Board of Directors of the Jewish Federation of Greater Seattle, in cooperation with the Jewish Studies Program of the Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington, established an annual lectureship at the University of Washington known as the Samuel and Althea Stroum Lectureship in Jewish Studies. This lectureship makes it possible to bring to the area outstanding scholars and interpreters of Jewish thought, thus promoting a deeper understanding of Jewish history, religion, and culture. Such understanding can lead to an enhanced appreciation of the Jewish contributions to the historical and cultural traditions that have shaped the American nation.

The terms of the gift also provide for the publication from time to time of the lectures or other appropriate materials resulting from or related to the lectures.

Contents

Preface and Acknowledgments

At the invitation of the University of Washington, I delivered the Samuel and Althea Stroum Lecture in April and May 1998. I want to thank Robert Stacey for the invitation, and my host, Naomi Sokoloff, and her colleagues for ten enjoyable and memorable days in Seattle, during which it uncharacteristically never rained.

Before going to Seattle, I spent several months researching and writing parts of this book in anticipation of the three public lectures. Several weeks before the scheduled trip, I realized that I did not want to read draft chapters from a book. And so, I made a set of outlines and quotations, as well as hundreds of slides, just for the lectures. I returned to the book from time to time, over the past four years, and completed it thanks to grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, and a triennial leave from Yale University for which I am extremely grateful.

I have tried to keep the appearance of this book as accessible to general readers as possible, while not stinting in the notes and bibliography to show scholars the basis for my findings. For this reason, I ask my colleagues in Judaica to overlook the fact that I have avoided using diacritical marks in transliterating Hebrew and related languages. Except for most proper names, letters alef in the middle of a word and ayin, wherever it appears in a word, are represented by an apostrophe (); heh and het are both h; samekh and sin, as s; tav and tet, by t; zayin and zadeh as z; kaf is k and quf is q, unless it is in an English spelling, such as Kaddish, or in a common spelling of a name, like Rabbi Akiva. Readers who know Hebrew will know the differences; I hope that those who do not will not mind the omission.

Hebrew and other foreign words that have become part of English are spelled in their English forms. Thus, a commandment is translated mizvah, but the English term bar mitzvah is spelled tz, not z. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.) has been my guide, and I have tried to be consistent, but there will be a few exceptions from time to time. Foreign terms are italicized the first time and romanized thereafter.

Among other rules that I have tried to follow: words I have added to quotations are in square brackets, but I supply the identification of biblical verses and translations of foreign terms in the text in parentheses. I have retained square brackets or parentheses as they appeared in the original quoted material. All references in the endnotes are found in short form throughout the book, even the first time, but they are all included in the comprehensive Bibliography, which is divided into Primary and Secondary Sources. The few abbreviations to rabbinic texts that I have used also appear there in their proper alphabetical location. For example, B. for Babylonian Talmud is in the Bibliography under Primary Sources, under B.

Among those colleagues and friends who have been especially helpful, I want to thank Elisheva Baumgarten, Robert Bonfil, Daniel Boyarin, Shaye J. D. Cohen, Yaakov Deutsch, Steven Fraade, Joseph Gutmann, Samuel Heilman, Elliott Horowitz, Gershon Hundert, Paula Hyman, Moshe Idel, Willis Johnson, David Kogen, David Kraemer, Vivian Mann, Michael Meyer, Carol Matzkin Orsborn, Julie Parker, Joel Rascoff, Benjamin Ravid, David Roskies, Shalom Sabar, Jonathan Sarna, Raymond P. Scheindlin, Menachem Schmelzer, Stuart Schoenfeld, Seth Schwartz, Mel Scult, Ephraim Shoham-Steiner, Don C. Skemer, Sol Steinmetz, Israel Ta-Shema, Roni Weinstein, and Chava Weissler.