(/)

2016-2020

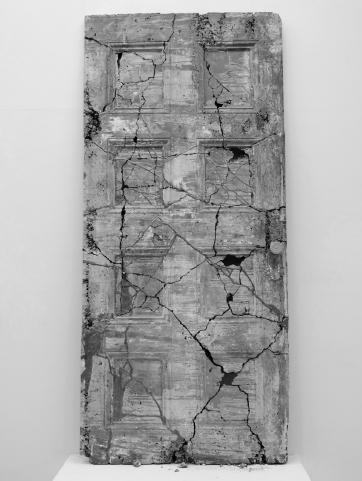

Atsushi Watanabe 2020

MONUMENT OF RECOVERY The Door

Atsushi Watanabe

Photo by Keisuke Inoue

Atsushi Watanabe 2020

Mental Health and Social Withdrawal in Contemporary Japan

This book examines the phenomenon of social withdrawal in Japan, which ranges from school nonattendance to extreme forms of isolation and confinement, known as hikikomori. Based on extensive original research, including interview research with a range of practitioners involved in dealing with the phenomenon, the book outlines how hikikomori expresses itself, how it is treated and dealt with, and how it has been perceived and regarded in Japan over time. The author, a clinical psychologist with extensive experience of practice, argues that the phenomenon although socially unacceptable is not homogenous and can be viewed not as a mental disorder, but as an idiom of distress, a passive and effective way of resisting the many great pressures of Japanese schooling and society more widely.

Nicolas Tajan is a program-specific associate professor in the Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies at Kyoto University, Japan.

Japan Anthropology Workshop Series

Series editor:

Joy Hendry, Oxford Brookes University

Editorial Board:

Pamela Asquith, University of Alberta

Eyal Ben Ari, Kinneret Academic College, Sea of Galilee

Christoph Brumann, Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Munich

Henry Johnson, Otago University

Hirochika Nakamaki, the Suita City Museum

Founder Member of the Editorial Board:

Jan van Bremen, University of Leiden

The Japanese Family

Touch, Intimacy and Feeling

Diana Tahhan

Happiness and the Good Life in Japan

Edited by Wolfram Manzenreiter and Barbara Holthus

Religion in Japanese Daily Life

David C. Lewis

Escaping Japan

Reflections on Estrangement and Exile in the Twenty-First Century

Edited by Blai Guarn and Paul Hansen

Women Managers in Neoliberal Japan

Gender, Precarious Labour and Everyday Lives

Swee-Lin Ho

Global Coffee and Cultural Change in Modern Japan

Helena Grinshpun

Inside a Japanese Sharehouse

Caitlin Meagher

Mental Health and Social Withdrawal in Contemporary Japan

Nicolas Tajan

For a full list of available titles please visit: www.routledge.com/Japan-Anthropology-Workshop-Series/book-series/SE0627

First published 2021

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2021 Nicolas Tajan

The right of Nicolas Tajan to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with Sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved: No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record has been requested for this book

ISBN: 978-0-8153-6574-7 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-351-26080-0 (ebk)

Typeset in Times New Roman

by KnowledgeWorks Global Ltd.

Contents

Table of Contents

Page List

Landmarks

Hikikomori phenomenon, far from being homogeneous, begins to appear as it really is: the history of a myriad of singular subjects who, despite themselves, draw attention to their absence while making social renunciation an idiom that is deeply subjective and eminently social. This quotation encapsulates some of the central issues of this fascinating and important work. Nicolas Tajan is not an anthropologist but a clinical psychologist who was brought by his topic of inquiry to act and proceed in his research more and more like an anthropologist. As the above mentioned sentence indicates hikikomori is not a psychiatric category showing this is one of the central aims of the book the term refers to the history of myriad singular subjects rather than to an ailment with clear characteristic traits. The point is not merely that this failure at being a homogeneous set of individuals or psychological characteristics reflects the difference between the method of the psychiatrist, who sees instances of particular diseases and categorizes them as depression or bipolar disorder, and that of the anthropologist, who seeks to encounter others as they are in their diversity, rather than to categorize them. The point rather is that the reason why hikikomori escapes psychiatric categorization is neither because these categories do not constitute knowledge nor because it is true that all medical categories subsume under a single term myriad singular subjects, but because hikikomori fails to become an object of psychiatric knowledge. It is not a mental disease but a psychosocial phenomenon.

The hikikomori does not ask anything from the psychiatrist, or the medical profession in general, or from any others in particular actually, hiding, shut in a room in a house that he or she rarely leaves. There is a paradox here in viewing these persons as patients. How do you meet someone who does not want to meet anyone? What if you succeed, is the person you met a hikikomori or not hikikomori anymore? This desire for isolation and loneliness, which Tajan describes as an idiom of distress, is eminently social and challenges the health professions. Here are persons who do not ask for help, do not come forward with their complaints, and therefore are only made into patients by others. Which happens only sometimes, when they are not hidden from view by the family from (and within) which they are hiding. In either case, they do not seek help, for whatever reason they have renounced asking.

The clinic has always been about responding to the patients demand, even if in many cases, this meant reinterpreting it in a different way. Medical and psychiatric categories are tools that help the specialist endowed with knowledge, called upon because of that knowledge, to respond to the patients demands. Hence the need for a different method and approach when the persons way to address others is silence, isolation, social renunciation; one that is not, or at least that is less, predicated on a hierarchical relation of knowledge and thus closer to that of anthropologists. Clinical psychologists interested in hikikomori have to do fieldwork. They cannot remain in their office waiting for the patients to come. They must go to them. This profoundly changes the relationship and indicates that these individuals in distress are not like those who can be analyzed, and disciplined through the use of psychiatric categories. In what ways are they different? This is what this book describes with finesse and attention and tries to interpret in a larger social and historical context.