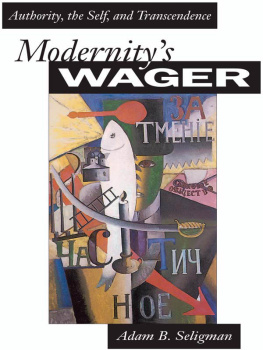

First published 1994 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1994 Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 9321107

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Seligman, A.

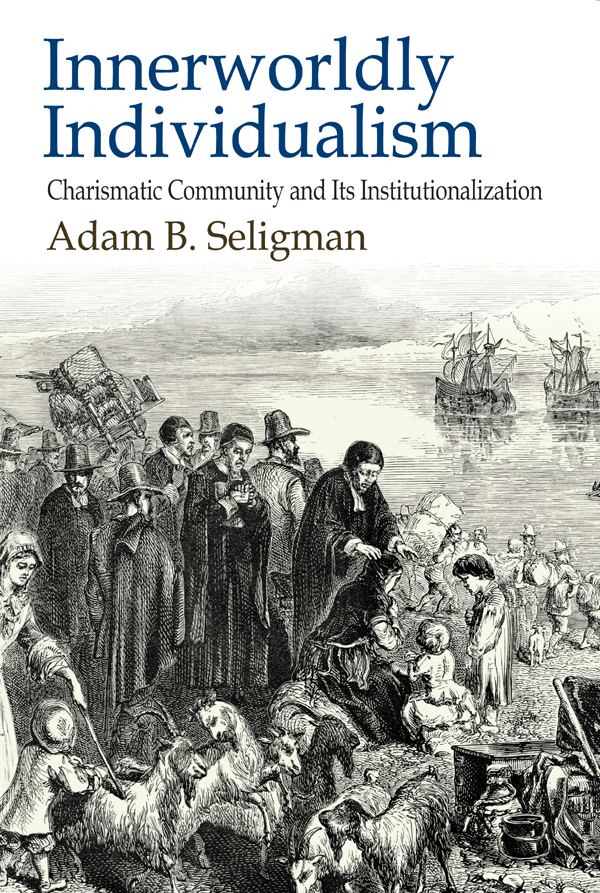

Innerworldly individualism : charismatic community and its institutionalization / Adam B. Seligman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1560001283 (cloth) : $34.95

1. New EnglandSocial conditions. 2. New England History Colonial period, ca. 16001775. 3. Civil societyNew England History17th century. 4. Group identityNew England History 17th century. 5. IndividualismNew EnglandHistory17th century. 6. PuritansNew EnglandHistory17th century. 7. Church and social problemsNew EnglandHistory17th century. 8. Sociology, ChristianNew EnglandHistory17th century. I. Title.

HN79.A11S45 1994

306' .0974dc20

9321107

CIP

ISBN 13: 978-1-4128-6293-6 (pbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-56000-128-7 (hbk)

Whatever else may characterize the civilization of modernity one thing is clear. Central to the modern worldview is the idea of the autonomous individual, imbued with moral agency as standing at the foundation of the social and cultural orders. From this view of the individual stems our contemporary ideas of justice and equity, our concerns with rights and entitlements, and, in fact, our conception of the proper or ideal models of the social order. It is this that sets off the civilization that developed in the Western European and North Atlantic communities at the end of the seventeenth and beginning of the eighteenth centuries from other social formations and indeed, to a large extent from their own premodern or traditional pasts.

This later statement needs some qualification. For as the work of scholars such as Ernst Troeltsch, Max Weber, Marcell Mauss, Benjamin Nelson, and, most recently, Luis Dumont have shown, it is impossible to understand the development of the idea of the individual without an appreciation of its roots in Christian civilization and the idea of, in Ernst Troeltschs terms, the individual-in-relation-to-God. Moreover, and in terms of the thesis associated most popularly with the work of Max Weber (but central to the writings of Troeltsch, Nelson, and Du-mont as well), it was only in the period of the Protestant Reformation and the transformation that ascetic-Protestantism engendered in the overall cultural assumptions of Western Christendom that the idea of the modern individual emerged.

This thesis is well known and does not warrant repeating here except to point out that it is still hotly debated. Today, ninety years have passed since Webers The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism was first published, and while we have accumulated a good-sized library of works dealing with Webers Protestant Ethic Thesis, we still have little sense of the concrete historical and sociological processes through which the modern idea of the individual (whose status was enshrined in the revolutions of the eighteenth century) emerged from the religious doctrines of seventeenth-century ascetic-Protestant sects. Equally problematic is the fact that most of the diverse groups of religious virtuosi who gathered in England, France, the Netherlands, Germany, New England, and elsewhere in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, to further the work of reforming the social and spiritual orders of the world, were tied together by intense bonds of spiritual brotherhood. Their venture was a communal one and they were, in every sense of the word, religious sects. What characterized them was less the individual-in-the-world and more a charismatic community of spiritual elect imbued with the Holy Light. This fact just exacerbates the problem of the emergence of modern individualism from the communities of seventeenth-century religious virtuosi. (As does the fact that those sectarian and Pietistic groups who did articulate a doctrine of free grace and individual electionsuch as Quakers and Anabaptistsdid not, on the whole, succeed in institutionalizing their religious doctrine beyond the boundaries of their own confession. This point is especially pertinent in the case of New Englandand later the United Stateswhich provided for Weber, as it does for us, the model for modern individualism in general.)

Indeed, what I would like to argue is that this matter of institutionalization, as idea and practice, stands as the central challenge to any attempt to understand the development of modern identities from the religious convictions of ascetic- Protestantism. The challenge then is twofold. On the historical level it involves analyzing the concrete social practices through which the religious doctrines of ascetic-Puritanism became, over the course of the seventeenth century, fundamental principles of modern social and political practice. On the theoretical level it involves explaining a seemingly intractable contradiction. For to become components of modern consciousness and sensibility, the religious doctrines of ascetic-Protestantism had to be, in some way, institutionalized within the collective. Yet, the very sectarian character of a virtuosi religion would seem, by definition, to preclude any such process of institutionalization. Weber himself, it may be noted, did notin his analysis of Puritanism in New Englandmanage to overcome this contradiction. Thus, his Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism analyzed the continuing importance of Puritan New England in the making of the American national identity, while in sections of Economy and Society he clearly sees New England Congregational Puritanism as losing its sectarian character at mid-century.

The very posing of this contradiction takes us, however, to the heart of our analysis and to the intensely communal nature of individual identities in the early modern period. Indeed, what is argued here is that any appreciation of the emergence of modern individual identities (in the eighteenth century) must be prefaced by an analysis of the changing terms of collective identities in the preceding century, which is our task here. Consequently, as we shall see, certain problems, of the institutionalization of ascetic-Protestantism and of the relations of religious virtuosi or sectarian religion to the world at large are thus central to our understanding of the modern world, however rooted they may seem to be in the problems and perspectives of a premodern and religious culture. They will, indeed, find a place of no little importance in the following analysis. For what I have attempted in this study is precisely to analyze the emergence of modern ideas of individual and collective identity in and through the concrete process of institutionalization that characterized ascetic-Protestantism in one seventeenth-century communitythat of New England Congregational Puritanism.