T he following selection of libraries is (almost) a random one, guided by the need to include certain institutions that must be on any survey of libraries, and by the wish to include a few others that are significant or outstanding in unique ways.

The great, important, and interesting libraries of the world are very numerousand it could be said that every institutional library, large or small, deserves to be in such a survey. This selection is representative of certain types of libraries, though it can only introduce them.

The reader may one day take a closer, personal, look at someand perhaps, also, at some of the others which are not here.

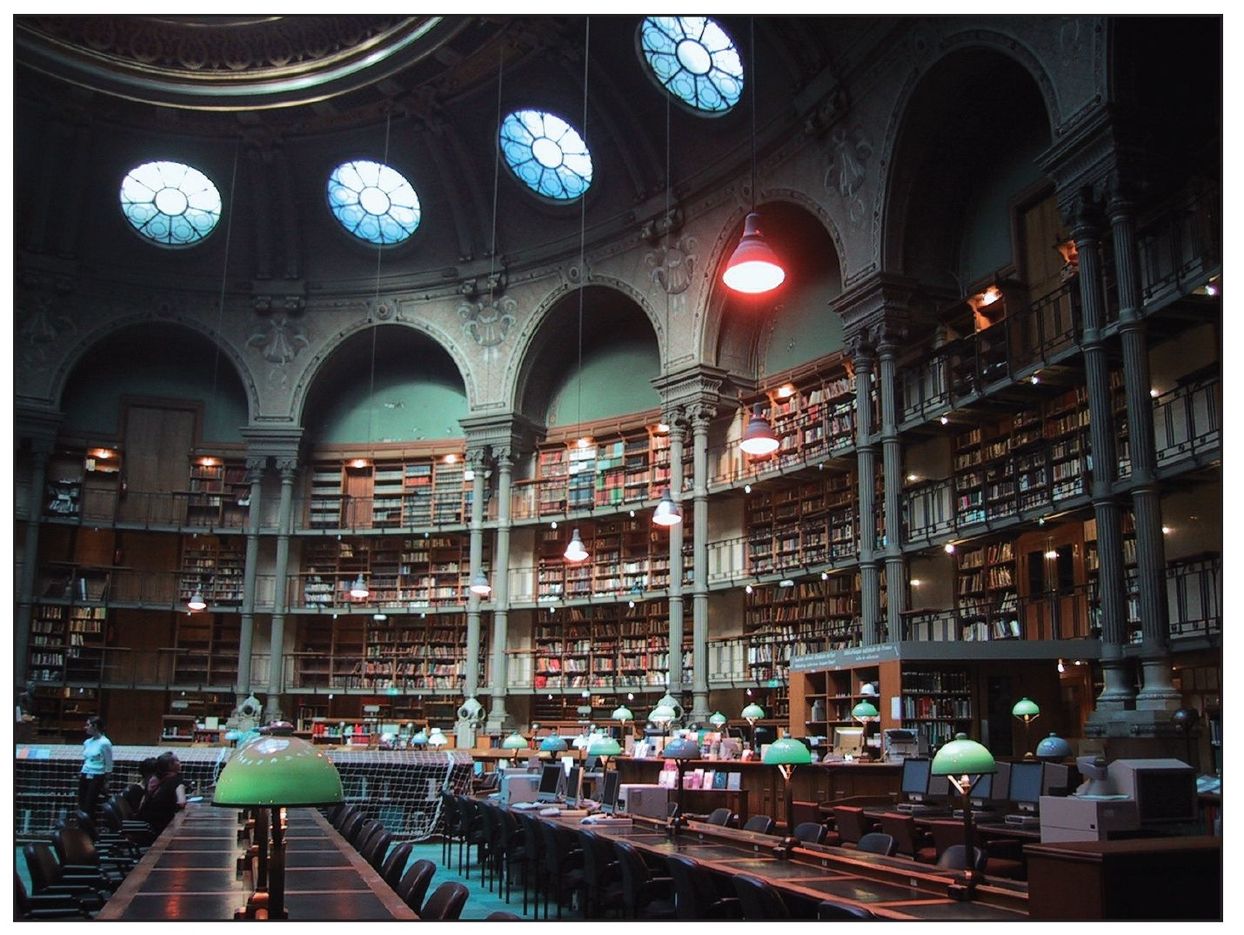

Bibliothque Nationale de France

The National Library of France, in Paris, has its origins in the royal library of Charles V (1338-80), founded at the Louvre castle in 1368. Known as The Wise, Charles built a library of 1,200 volumes, including classical works translated into French by royal commission. The collection was sold to an English duke in 1425, but Charles VIII (1470-98) reestablished the royal library, building on the libraries of previous kings.

This library developed steadily with each royal house until it was opened to the public in 1692. Among the major acquisitions of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was the purchase of 120,000 engravings, supplemented by bequests of engravingscornerstone of the Department of Prints. During the French Revolution, when the new government seized the private collections of aristocrats and clerics, the library received the confiscated books. Officially called the Bibliothque Nationale in 1792, its holdings grew to 300,000 volumes.

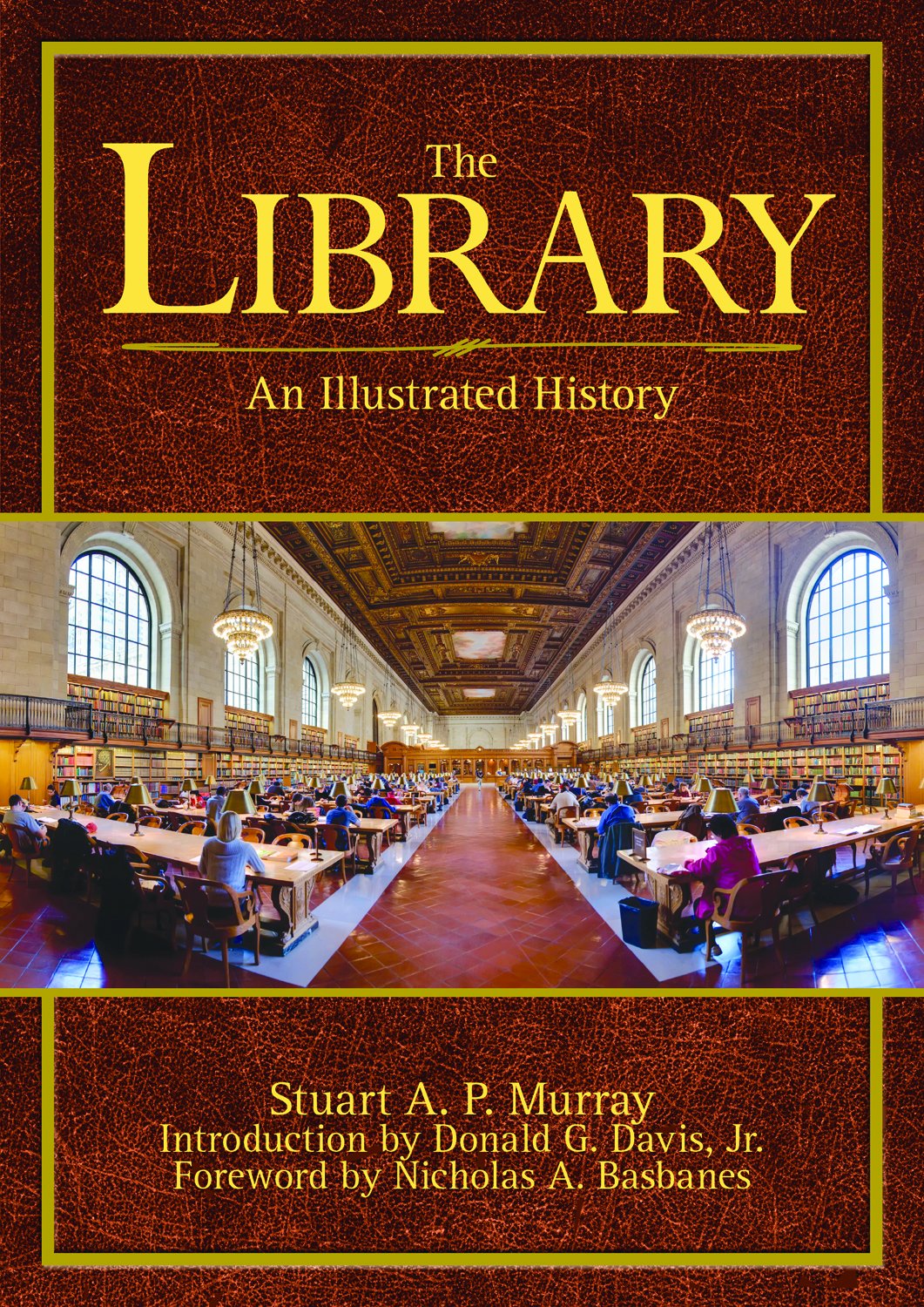

Bibliothque Nationale de France, Paris.

The Napoleonic Wars, ending in 1815, saw the addition of spoils of war to the library. Conquest and confiscation brought in another quarter million books, 15,000 manuscripts, and several thousand prints. A good deal of the spoils, however, were returned to their original countries by peace treaties.

In 1868, the French government erected new buildings to house the collection, which by then had been renamed the Imperial National Library. Over the next hundred years, various organizational changes and governmental decrees changed the librarys statusit belonged to the education ministry, then was part of a consortium of libraries, then fell under the ministry of universities, and then the ministry of culture, and at last, in 1983, became a division of the national government.

In the final decades of the century, new library facilities expanded and updated the Bibliothque Nationale to make it one of the largest and most modern in the world. The librarys cultural mission includes conserving and making available books published in France. Restoration studios offer advice and technical assistance, and a reproduction department converts books, images, and documents to microform and digital formats. The library also exhibits paintings and antiques of French culture, including the world globes made for Louis XIV.

A staff of 2,700 manages more than 13 million books, including 5,000 Greek manuscripts and 200,000 rare and precious titlesone-third from foreign lands. There are more than 350,000 periodical titles; 650,000 maps; 10,000 atlases; and 15 million images, including drawings, engravings, photographs, and posters. The manuscripts department has 350,000 volumes, and there is also a collection of 300,000 coins.

The Bibliothque Nationale holds 1.5 million musical scores, archives, and reference works, and 1.1 million records and videotapes. Its digital library, available online, is steadily growing, with more than 200,000 scanned volumes and images.

British Library

Established by Parliament in 1753 as an afterthought to the newly opened British Museum, the national library was essentially a division of printed books and manuscriptseven though the head of the museum held the title Principal Librarian.

The first library collections included the Cottonian Library holdings, owned by the government since 1700. Other private collections bequeathed or purchased were also part of the first collection, and were known as foundation collections. They included the books, manuscripts, antiquities, and curios of the prosperous physician, Sir Hans Sloane. Managing the Sloane collection was one of the key reasons for establishing the museum and library.

In 1759, King George II (1683-1760) presented the collection of the Old Royal Library (that of the kings and queens of England). In this library were nine thousand printed books and many important manuscripts. Further royal and private donations built up the library, which had little in the way of capital for acquisitions. The thrifty trustees did, however, find the funds to acquire the private papers of an important Elizabethan minister in 1807.

Adding to the foundation collections, George IIIs library was donated by the Crown, expanding by half the collection of printed books, and the library continued to count on aristocratic donations for its growth. The librarys true expansion came in 1837 after Antonio Panizzi was appointed Keeper of Printed Books. Panizzis first task was to move the book collection (235,000 volumes) to a new building, and he also undertook the enormous task of developing a new cataloging system.

Panizzi obtained acquisition funds and convinced Parliament to enforce the law that required legal deposit titles to be sent by publishers to the library. He also planned the massive circular Reading Room, opened in the quadrangle of the museum in 1857. Made of cast iron, concrete, and glass, the Reading Room opened in 1857, with twenty-five miles of shelves. Patrons had to apply in writing for a readers ticket from the principal librarian.