First published in 1944 by

Routledge, Trench, Trubner and Co., Ltd

Reprinted 1998, 2000

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Transferred to Digital Printing 2007

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group

1944 H. C. Dent

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

The publishers have made every effort to contact authors/copyright holders of the works reprinted in The International Library of Sociology. This has not been possible in every case, however, and we would welcome correspondence from those individuals/companies we have been unable to trace.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Education in Transition

ISBN 0-415-17759-6

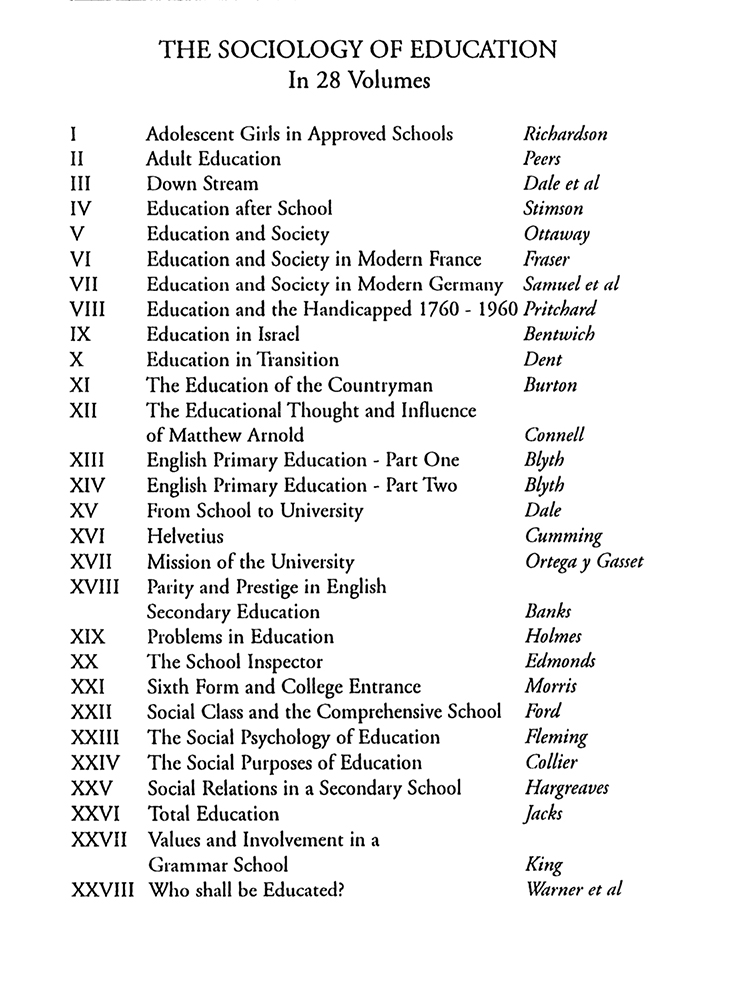

The Sociology of Education: 28 Volumes

ISBN 0-415-17833-9

The International Library of Sociology: 274 Volumes

ISBN 0-415-17838-X

Publisher's Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original may be apparent

It is broadly true to say that up to the outbreak of the present war the average English man or woman was not interested in education. Today the reverse is the case; there is throughout the country the keenest interest. It would be idle to pretend that this is yet universal; but it is undeniably widespread, it is found among all sorts and conditions of people, and it grows daily in extent and intensity.

With the growth of interest there is emerging a broader and deeper conception of the meaning, the purpose and the scope of education. The intimate relationship between the educational system and the social order is being increasingly realized. It is becoming widely recognized that education is one of the main instruments for promoting the development of society, and that consequently if we desire a new order of society one of the inescapable conditions is a new order in education.

Much planning is being done by educationists, and others, of such a new order. The proposals some have in mind would revolutionize English education. Their aim is to deepen and clarify its purpose, to unify its administration, increase its diversity of provision, extend its period, bring its content up to date, and relate the entire educational process to the social context in a manner and to a degree hitherto unknown in this country or any other.

Such plans are not impossible of achievement. They are in no sense Utopian; on the contrary, they are but logical, and practicable, developments of already existing trends. They are revolutionary only in the boldness of their conception and the far-reaching nature of their vision. And they are the only safe plans. " In dealing with this question of education," W. E. Forster told the Cabinet in 1870, "boldness is the only safe policy. Any measure which does not profess to be complete will be a certain failure," If those words were true seventy years ago, they are far more so today. For, whether we like it or no, education in England is in transition. The old order is dead; the new is being shaped before our eyes, in part deliberately, but more, as yet, by circumstance. Time and ourselves alone will decide whether intention or circumstance shall prevail.

Little as there has been of structural change in the educational set-up during the war (though there has been more than most people realize) the educational order of 1939 has passed beyond recall. It died on September 1 of that year, the day on which evacuation began. It can never be reborn; there has already been too much of change. How much, this book attempts to show. In a narrative mainly factual, and chronological save that the episodic method has been used to analyse out the main elements of change, I try here to show how impressive has been the impact of the war on English education and how far we have already travelled away from 1939.

It is a story of surpassing interest, which I trust I have not too much dulled: the story of a period of dynamic change, which has witnessed the all but disintegration of a great national institution; its recuperation from what might well have been a mortal blow, and its restoration to something resembling (yet how different from!) the previous state of affairs; its continuous adaptationat times spectacular, at others almost imperceptible, yet never ceasingto war-time conditions and exigencies. And arising out of all this, a mighty ferment of ideas, a great surging impulse to reform, to plan a new and better order in education and society, an order rid for ever of the inequalities, injustices and inadequacies of the order of 1939.

These four processesof disintegration, recuperation, adaptation, and fermenthave been going on coincidentally, acting and reacting upon each other in most intimate and intricate fashion. I have in this book attempted to separate them out, and have dealt with each in a chapter by itself. The method is not ideal; it tends to over-simplification and inevitably involves overlapping. But I felt it to be preferable to the alternative of a wholly chronological account, which would of necessity have had perpetually to leap from one aspect of change to another, and would, I feared, have almost certainly obscured what I want above all else to make clearthat during, and because of, these four years of war English education has literally " suffered a sea change". It is, by the force of circumstance rather than by conscious endeavour, being transformed into "something new and strange", the shape of which we have not known before.

This transformation is still in full tide. Its total significance is as yet impossible to assess. This book pretends to be no more than a crude first contribution towards that assessmentwhich must be made, and with as little delay as possible. For man must be master of circumstance, or chaos and perversion will ensue. Much that has happened in the field of English education during the past four years can hardly fail to exert a beneficent influence on the future; but of not all that has happened can this be said. There are trends which may prove sinister or retrograde. Emergency measures have been taken which are doubtless necessary in war-time, but which must not be allowed to receive the stamp of permanency.

They may do so unless we are on our guard. It is imperative that we be constantly on the alert to distinguish the good strands from the bad in this war-time pattern that is being woven, so that when peace returns and we begin to weave what we hope may be a more permanent pattern in education all the strands that are good may be preserved and used, all that are not good discarded and done away with. This war period is essentially an abnormal period; and every element of change it introduces must be scrutinized with that in mind.