S O W HAT, OR H OW TO M AKE F ILMS WITH W ORDS

PILOSOPHY AND THE MOVING IMAGE

Series editor Brian Price

Superimpositions: Philosophy and the Moving Image takes philosophy and visual media as related practices. Books in this series do not simply apply philosophy as a method for reading art or redundantly representing its extant ideas. Following the visual logic of superimposed imagery, we see what philosophy and art share and what remains distinct, and distinctly generative. Superimposition, moreover, resembles thinking itself: an encounter with an object summons the idea of something like it and yet not the same. Twentieth-century philosophers turned increasingly to literature to replace generalized axioms with thick descriptions of the world and our psyches. Superimpositions takes the moving image, in all its limitations and possibilities, as central to the task of twenty-first-century philosophy and its refusal to foreclose either thought or difference.

So What, or How to Make Films with Words

Alexander Garca Dttmann

N ORTHWESTERN U NIVERSITY P RESS

E VANSTON, I LLINOIS

Northwestern University Press

https://www.nupress.northwestern.edu

Copyright 2023 by Northwestern University. Published 2023 by Northwestern University Press. All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Garca Dttmann, Alexander, author.

Title: So what, or How to make films with words / Alexander Garca Dttmann.

Other titles: So what | Superimpositions.

Description: Evanston, Illinois : Northwestern University Press, 2023. | Series: Superimpositions | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022051906 | ISBN 9780810145351 (paperback) | ISBN 9780810145368 (cloth) | ISBN 9780810145375 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Motion picturesPhilosophy.

Classification: LCC PN1995 .G269 2023 | DDC 791.4301dc23/eng/20221101

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022051906

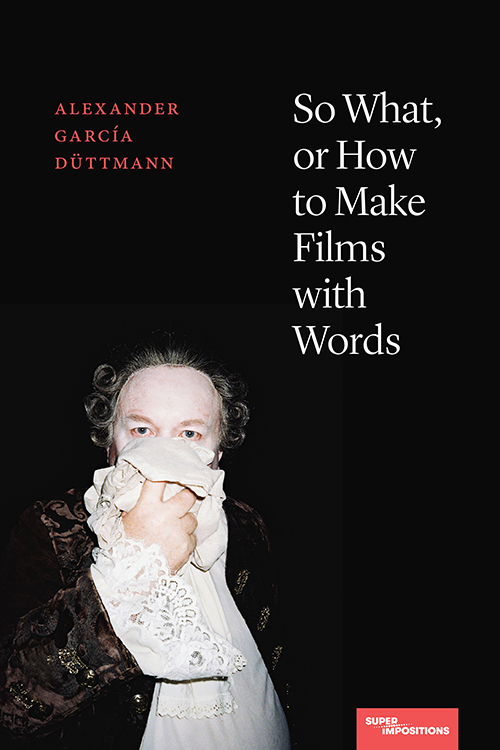

Cover image: The author, on the set of Albert Serras film Libert (2018). Copyright Romn Yn.

Cover design: Monograph / Matt Avery

A note to the reader: This e-book has been produced to offer maximum consistency across all supported e-readers. However, e-reading technologies vary, and text display can also change dramatically depending on user choices. Therefore, you occasionally may encounter small discrepancies from the print edition, especially with respect to indents, fonts, symbols, and line breaks. Furthermore, some features of the print edition, such as photographs, may be missing due to permissions restrictions.

Contents

BRIAN PRICE

Brian Price

In 1930, Wittgenstein was asked to write a foreword to a volume of his own papers, edited by Rush Rees and ultimately given the title Philosophical Remarks. In his notebook that same year, Wittgenstein sketched a draft of the foreworda slightly different version than the one that eventually appearedand reflected on the process of having done so. He came to the conclusion that the danger in a long foreword is that the spirit of a book has to be evident in the book itself and cannot be described. For if a book has been written for just a few readers that will be clear just from the fact that only a few people understand it. The book must automatically separate those who understand it from those who do not. Even the foreword is written just for those who understand the book.

On the one hand, the foreword is a form of betrayal by redundancya way of failing readers who are already complicit and prepared to read what they know they cannot know in advance, who wish not to. Why else come to the book, in the first place, if not for what one cannot expect? On the other hand, the foreword runs the risk of translating the work for a marketplace, one that has become indistinguishable from art and politics. It runs the risk of making philosophy instrumental and thus something other than philosophy. To be in sympathy with the spirit in which the book was written, then, is to remain outside ofand forever inassimilable toa civilization in which the zeal for efficiency depends on the end of questioning. The risk of the foreword is that the book itself will be shownand in that way, remadeto conform to a culture that cares only to extinguish the work by consuming the work; to understand the work quickly, such that the citation announces belonging, marks ones adherence to an industry standard, where once citation might simply have been a way of honoring an insight for its own sake, which never precludes the real effect it has on those who encounter it. Perhaps what I am describing hereor what is at risk of extinctionis something closer to the recitation from memory of a beloved poem that is not ones own.

Or, perhaps, what I am describing is a scene from the filmmaker Todd Phillipss neglected masterpiece Old School (2003). The film, you may recall, is about three friends, significantly beyond their university years, who decide to establish a fraternity in a house that Mitch (Luke Wilson) has rented following the death of a professor who lived there, on campus, for forty years, and after Mitch discovered that his girlfriend was having orgies at his house without him. Hence the need for a new place. Once Mitch moves in, he and Beanie (Vince Vaughn) and Frank (Will Ferrell) decide to throw a college party, the overwhelming success of which leads the dean to rezone the house so that it can only be used for university business. At that point, Beanie decides that the only solution is to develop an alternative fraternity, so as to meet the minimal condition of allowing the house to remain university property, even though no one there belongs to the university in a conventional way. When asked in an ad hoc press conference at the house about the nature of the association he intends to keep with the university, Beanie tells the reporter, whom he chides for asking such a question in the first place, Legally speaking, there will be a loose affiliation. But we will give nothing back to the academic community, as well as provide no public service of any kind. This much I promise you. What Beanie promises, in other words, is that what is happening here works and that what works owes nothing to the way of the social as it is and as it wishes to remain, even if what works does so within a space zoned against the appearance of what the university cannot describe or imagine for itself.

For many reasons, these two very different scenesWittgensteins resistance to the form of the foreword and the refusal of adherence to official culture in Old Schoolhave been playing in my mind since I began to think about writing a foreword to the book before you, Alexander Garca Dttmanns So What, or How to Make Films with Words, the inaugural publication in this series, Superimpositions: Philosophy and the Moving Image. As readers of Garca Dttmanns philosophy know well, the work is marked by a seriousness that takes assimilation as a problem to be overcome and a possibility as what may remain in view but never as what should be seen, done, or made in the image ofnot to mention by a sustained reflection on what seriousness consists in, as was the case for Wittgenstein, too. In Visconti: Insights into Flesh and Blooda book that is, for me, as important to film philosophy as Deleuzes Cinema 1 and Cinema 2, and Stanley Cavells

Next page