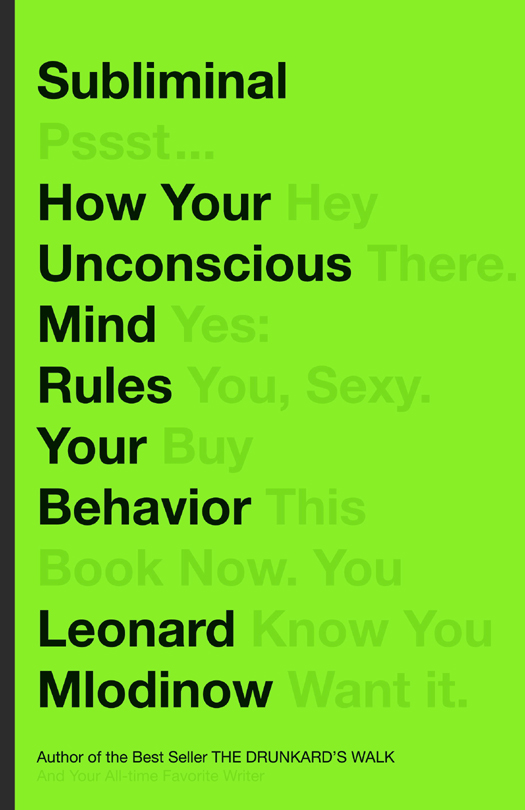

Copyright 2012 by Leonard Mlodinow

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mlodinow, Leonard, [date]

Subliminal : how your unconscious mind rules your behavior / Leonard Mlodinow.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN: 978-0-307-90744-8

1. Subconsciousness. I. Title.

BF315.M56 2012 154.2dc22 2011048098

www.pantheonbooks.com

Cover design by Peter Mendelsund

v3.1

To Christof Koch, K-lab,

and all those who have dedicated their careers

to understanding the human mind

Contents

The hidden role of our subliminal selves what it means when you dont call your mother

The two-tier system of the brain how you can see something without knowing it

How the brain builds memories why we sometimes remember what never happened

The fundamental role of human social character why Tylenol can mend a broken heart

How we communicate without speaking how to know whos the boss by watching her eyes

What we read into looks, voice, and touch how to win voters, attract a date, or beguile a female cowbird

Why we categorize things and stereotype people what Lincoln, Gandhi, and Che Guevara had in common

The dynamics of us and them the science behind Lord of the Flies

The nature of emotions why the prospect of falling hundreds of feet onto large boulders has the same effect as a flirtatious smile and a black silk nightgown

How our ego defends its honor why schedules are overly optimistic and failed CEOs feel they deserve golden parachutes

Prologue

These subliminal aspects of everything that happens to us may seem to play very little part in our daily lives. But they are the almost invisible roots of our conscious thoughts. CARL JUNG

I N J UNE 1879, the American philosopher and scientist

Peirce confidently approached his suspect, but the man called his bluff and denied the accusation. With no evidence or logical reason to back his claim, there was nothing Peirce could dountil the ship docked. When it did, Peirce immediately took a cab to the local Pinkerton office and hired a detective to investigate. The detective found Peirces watch at a pawnshop the next day. Peirce asked the proprietor to describe the man whod pawned it. According to Peirce, the pawnbroker described the suspect so graphically that no doubt was possible that it had been my man. Peirce wondered how he had guessed the identity of the thief. He concluded that some kind of instinctual perception had guided him, something operating beneath the level of his conscious mind.

If mere speculation were the end of the story, a scientist would consider Peirces explanation about as convincing as someone saying, A little birdie told me. But five years later Peirce found a way to translate his ideas about unconscious perception into a laboratory experiment by adapting a procedure that had first been carried out by the physiologistchance. And when Peirce and Jastrow repeated the experiment in other contexts, such as judging surfaces that differed slightly in brightness, they obtained a comparable resultthey could often correctly guess the answer even though they did not have conscious access to the information that would allow them to come to that conclusion. This was the first scientific demonstration that the unconscious mind possesses knowledge that escapes the conscious mind.

Peirce would later compare the ability to pick up on unconscious cues with some considerable degree of accuracy to a birds musical and aeronautic powers it is to us, as those are to them, the loftiest of our merely instinctive powers. He elsewhere referred to it as that inward light a light without which the human race would long ago have been extirpated For over a century now, research and clinical psychologists have been cognizant of the fact that we all possess a rich and active unconscious life that plays out in parallel to our conscious thoughts and feelings and has a powerful effect on them, in ways we are only now beginning to be able to measure with some degree of accuracy.

Carl Jung wrote, There are certain events of which we have not consciously taken note; they have remained, so to speak, below the threshold of consciousness. They have happened, but they have been absorbed subliminally. The Latin root of the word subliminal translates to below threshold. Psychologists employ the term to mean below the threshold of consciousness. This book is about subliminal effects in that broad senseabout the processes of the unconscious mind and how they influence us. To gain a true understanding of human experience, we must understand both our conscious and our unconscious selves, and how they interact. Our subliminal brain is invisible to us, yet it influences our conscious experience of the world in the most fundamental of ways: how we view ourselves and others, the meanings we attach to the everyday events of our lives, our ability to make the quick judgment calls and decisions that can sometimes mean the difference between life and death, and the actions we engage in as a result of all these instinctual experiences.

Though the unconscious aspects of human behavior were actively speculated about by Jung, Freud, and many others over the past century, the methods they employedintrospection, observations of overt behavior, the study of people with brain deficits, the implanting of electrodes into the brains of animalsprovided only fuzzy and indirect knowledge. Meanwhile, the true origins of human behavior remained obscure. Things are different today. Sophisticated new technologies have revolutionized our understanding of the part of the brain that operates below our conscious mindwhat Im referring to here as the subliminal world. These technologies have made it possible, for the first time in human history, for there to be an actual science of the unconscious. That new science of the unconscious is the subject of this book.

P RIOR TO THE twentieth century, the science of physics described, very successfully, the physical universe as it was perceived through everyday human experience. People noticed that what goes up usually comes back down, and they eventually measured how quickly the turnaround occurs. In 1687 Isaac Newton put this working understanding of everyday reality into mathematical form in his book Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica; the title is Latin for Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. The laws Newton formulated were so powerful that they could be used to accurately calculate the orbits of the moon and faraway planets. But around 1900, this neat and comfortable worldview was shaken. Scientists discovered that underlying Newtons everyday picture is a different reality, the deeper truth we now call quantum theory and relativity.

Scientists form theories of the physical world; we all, as social beings, form personal theories of our social world. These theories are part of the adventure of participating in human society. They cause us to interpret the behavior of others, to predict their actions, to make guesses about how to get what we want from them, and to decide, ultimately, on how we feel toward them. Do we trust them with our money, our health, our cars, our careers, our childrenor our hearts? As was true in the physical world, in the social universe, too, there is a very different reality underlying the one we naively experience. The revolution in physics occurred when, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, new technologies exposed the exotic behavior of atoms and newly discovered subatomic particles, like the photon and electron; analogously, the new technologies of neuroscience are today enabling scientists to expose a deeper mental reality, a reality that for all of prior human history has been hidden from view.