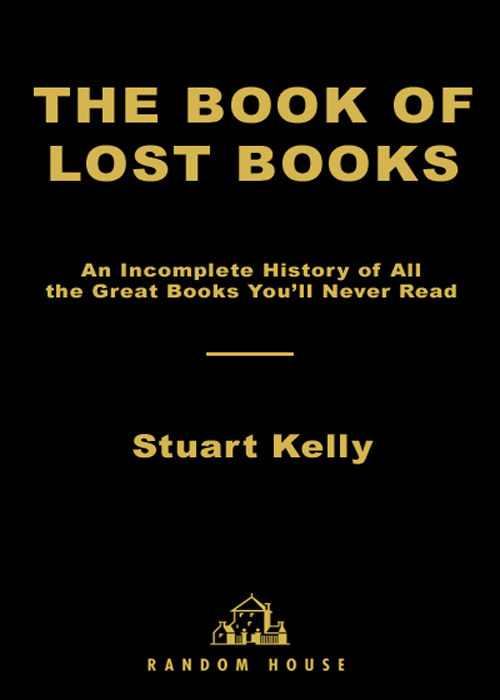

Table of Contents

This book is for Sam, who found me

Hence, perpetually and essentially, texts run the risk of becoming definitively lost. Who will ever know of such disappearances?

JACQUES DERRIDA, Platos Pharmacy

Introduction

Ill burn my booksah, Mephistophilis CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE, Doctor Faustus

MY MOTHER CLAIMS it started with the Mr. Men series of childrens books. In a well-rehearsed pantomime of parental exasperation, she recounts how, after a family relative had given me a copy of one of Roger Hargreavess stories, every holiday jaunt, weekend outing, and Saturday shopping trip became a single-minded trawl of bookshops until I had every single one of the series. Mr. Bump needed Mr. Nosey, Mr. Tickle was lonely without Mr. Chatterbox. After I had finished this first collection I swiftly became obsessed, I forget for what reason, with the Dr. Who novelizations; this was followed by Fighting Fantasy dice and decision books, and, as I approached my teens, Agatha Christie paperbacks.

A pattern began to develop; a pattern that would turn obsessive. Having one or some of the titles within any given series was not sufficient; I seemed to be afflicted with a relentless monomania for all, a near-compulsive necessity for closure and completeness. I even kept a Book of Lists, to reassure myself that I really did know every episode of Dr.Who, with checks by the ones I had bought and annotations about the ones that had never been novelized. When all of Agatha Christies books were reissued with newly designed covers, the idea of having mismatched volumes struck me as unspeakably grotesque. I stalked the old stock, ferreted for the forgotten copies at the back of the shelves.

It must have been with some trepidation, on my fourteenth Christmas, that my parents watched me unwrap a Complete Works of Shakespeare (Chancellor Press, 1982, printed in Czechoslovakia) and a selection of Wordsworth (by W. E. Williams, introduction by Jenni Calder, Penguin Poetry Library, 1985). I presume that they were hoping that Literaturewith a capital Lwas a large enough field in which my fixation might peter out.

Instead, Literature drove my zeal to new heights. The itch became a palpable rash when I started studying Greek (initially as a shameless ruse to avoid sports). Having saved up months of weekend-job wages, and having starved myself rationing lunch money, I binged on Penguin Classics of Hellenic drama: two volumes of Aeschylus, two of Sophocles, three of Aristophanes, four of Euripides, and a solitary Menander. The first shock to my well-ordered system came as I peeled back the smart covers and began to browse through the introductions. I was under the impression that I had just bought all of Greek drama, yet the prefaces and commentaries doomfully tolled otherwise: Aeschylus, whose seven plays I was holding, had actually written eighty; there should have been thirty-three volumes of Sophocles, not a mere brace... and so on.

The second, more grievous realization came when reading note 61 to Aristophanes play Thesmophoriazusae: Agathon, one of the most celebrated tragedians of the day, was forty-one when this play was produced. None of his works has survived. None? Not a chorus, not a speech, not a hemistich? It seemed unthinkable.

This, I decided, at the age of fifteen, was a situation I should rectify. I started compiling a List of Lost Books. It quickly superseded my Book of Lists with its Everyone in Star Wars That Wasnt Made into a Figure, Dr. Who Episodes Lost by the BBC, and even the list of books that I should read. This new list would be of the impossible and the unknowable, of books that I would never be able to find, let alone read.

It soon became clear that the subject was not limited to the Greeks, who, after all, had managed to keep on existing through Roman arrogance, Christian lack of interest, and a certain caliphs censorious view of libraries in general and the Alexandrian Library specifically.

From Shakespeare to Sylvia Plath, Homer to Hemingway, Dante to Ezra Pound, great writers had written works I could not possess. The entire history of literature was also the history of the loss of literature.

It is intrinsic to the nature of literature that it is written: even work initially preserved in the oral tradition only truly becomes literature when it is written down. All literature thus exists in a medium, be it wax, stone, clay, papyrus, paper, or evenas in the case of the Peruvian knot language, Khipurope. Since it has a material dimension, literature itself partakes of the vulnerability of its substance. Every element conspires against it: flame and flood, the desiccating air that corrupts, the loamy earth that decays. Paper is particularly defenseless: it can be shredded and ripped, stained and scrubbed away. Countless living things, from parasites and fungi to insects and rodents, can eat it: it even eats itself, burning in its own acids.

The simplest form of loss is destruction. Though the Roman poet Horace proclaimed, I have built a monument more durable than bronze, he expressed a hope about his work, not a certainty. The nineteenth-century poet Gerard Manley Hopkins burned all of his early poetry, as he dedicated his life to the beauty of God. James Joyce petulantly flung Stephen Hero, the first draft of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, into the fire, but did not prevent his wife from saving what she could of it. Mikhail Bakhtin, exiled in Kazakhstan, used his work on Dostoyevsky as cigarette papers, after having smoked a copy of the Bible.

Some writings are absent, presumed destroyed: Socrates, while in prison awaiting his execution, wrote versifications of Aesops Fables. None of these have survived, and we rely on Platos remembered and invented dialogues to catch even an echo of what Socrates himself might have written. Similarly, at some point, the only text of Aristotles second book of Poetics was lost, and even the first book is made up from students notes. A similar fate happened centuries later to Ferdinand de Saussures Course in General Linguistics. When the publisher John Calder had to hastily relocate his offices in late 1962, many manuscriptsincluding The Sowing, the third part of Lars Lawrences trilogy, and Angus Heriots The Lives of the Librettistswere left behind in the old premises. The building, unpublished works and all, was demolished. If any undiscovered genius had sent his sole copy to Calder, undiscovered he would remain.

There are other works that are lost in the sense of being misplaced. A suitcase containing Malcolm Lowrys Ultramarine was stolen from his publishers car, and the version we have had to be reconstructed from what was left in Lowrys wastebasket. Allen Ginsberg recollected hearing fellow Beat poet Gregory Corso reading in a lesbian bar in the Village, though you can search in vain through Corsos published oeuvre to find a poem with the line he remembered: The stone world came to me, and said Flesh gives you an hours life. How Ginsberg knew that Flesh was capitalized is a moot point.

There are also those manuscripts that meet an untimely end, whose authors mortal existence is concluded before their work. The medieval Scottish poet William Dunbar wrote a haunting elegy for many of his dead fellow writers: of the twenty-two poets he lists, there are ten about whom we know nothing whatsoever. Virgil left instructions for

Next page