HISTORY

John H. Arnold

New York / London

www.sterlingpublishing.com

STERLING and the distinctive Sterling logo are registered trademarks of Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

387 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016

Published by arrangement with Oxford University Press, Inc.

2000 by John H. Arnold

Illustrated edition published in 2009 by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Additional text 2009 Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Distributed in Canada by Sterling Publishing

c/o Canadian Manda Group, 165 Dufferin Street

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M6K 3H6

Book design: The DesignWorks Group

Please see picture credits on page 181 for image copyright information.

Manufactured in the United States of America

All rights reserved

Sterling ISBN 978-1-4027-6892-7

For information about custom editions, special sales, premium and corporate purchases, please contact Sterling Special Sales Department at 800-805-5489 or .

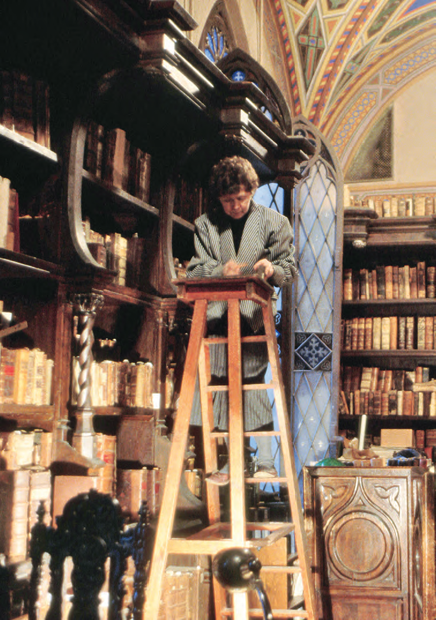

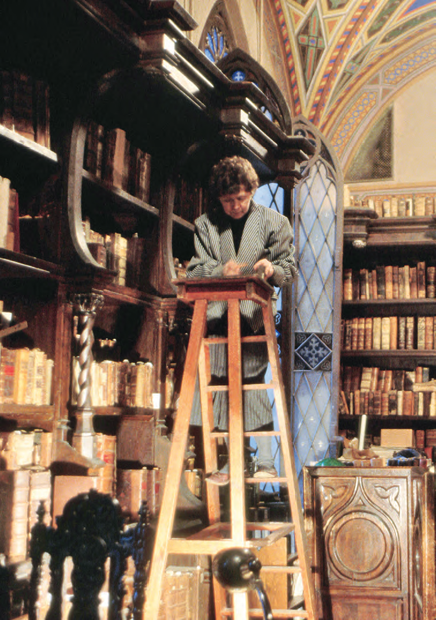

Frontispiece: An archivist at the National Library of Russia examines the Ostromir Gospel in 1993; the gospel is believed to be Russias oldest surviving document.

For Mum, Dad, Ruth, and Victoria

CONTENTS

THERE ARE PERHAPS THREE kinds of books one can write on the subject of history in general. One is a how-to guide to practice. Another is a philosophical investigation into theories of knowledge. The third is a polemic supporting a particular approach. This book is an introduction to history, and cannot claim to be fully any of these things, although it takes a little from each. Overall, however, it is intended as a work of enthusiasm. What is written here presents my views on what history is, how it is researched, and what it is for. I have, however, always tried to indicate that there are other paths to follow, other arguments to discover; and I hope that the reader might be tempted into some further exploration.

The book is loosely arranged into three sections. The first three chapters aim to raise certain questions, engage the readers interest, and describe (in brief terms) what history has been in the past. Chapters four and five attempt to show how one might set about doing history, first by working with sources and secondly by thinking about interpretations. The final chapters present some thoughts on the status and meaning of history and truth, and why history matters.

The chapters here have had many readers prior to their final versions, and I have incurred great debts toward a number of people who have set me straight on various topics. In particular, I must thank Barbara MacAUan, an expert on East Anglian migration to the New World, who first set me on the trail of George Burdett. Without her extreme generosity chapter four would not have been written. Any remaining foolishness, on this or any other area, is entirely my own property. Those others exculpated of guilt, but deserving of gratitude, include the following: Edward Acton, Katherine Benson, Peter Biller, Stephen Church, Shelley Cox, Simon Crab tree, Richard Crockett, Geoff Cubitt, Simon Ditchfield, Victoria Howell, Chris Humphrey, Mark Knights, Peter Martin, Simon Middleton, George Miller, Carol Rawcliffe, Andy Wood, and a host of anonymous readers at OUP. For what they have taught me about history, I have to thank the staff and students at the Department of History and the Centre for Medieval Studies at the University of York, and the schools of History, and of English and American Studies, at the University of East Anglia. Lastly, I have the longest debt to my father, who is always willing to argue about history and to tell me why Im wrong.

The ruin of the medieval French fortress Chteau de Queribus, in the Pyrnes, towers above the rocky landscape of southern France. Queribus, the last stronghold of the Cathars, fell to Catholic forces in 1255.

HERE IS A TRUE STORY . In 1301 Guilhem de Rodes hurried down from his Pyrenean village of Tarascon to the town of Pamiers, in the south of France. He was on his way to visit his brother Raimond, who was a monk in the Dominican monastery there. The journey was a good eighteen miles (thirty km) along the gorge of the river Ariege, and it would take Guilhem at least a day to reach his destination, traveling as he was on foot. But the reason for his trip was urgent: his brother had sent him a letter warning that both of them were in great danger. He had to come at once.

When he reached the monastery at Pamiers, his brother had frightening news. Raimond told him that a certain beguin (a kind of quasi-monk, who did not belong to any official religious order) had recently visited the monastery. He was called Guilhem Djean, and he posed a real threat to the brothers. Djean had apparently offered to help the Dominicans catch two hereticsPierre and Guilhem Autierwho were based in the Pyrenean village of Montaillou. He knew about the heretics because a man, who had given him shelter for the night, up in the mountain villages, had innocently offered to introduce Djean to them, thinking he might join their faith. Djean had met the Autiers, and gained their trust; now he could betray them.

But what really terrified Raimond was that Djean had also claimed that the heretics had a spy within the monastery. This spy, the beguin said, was linked to the heretics through his brother, a member of the laity, and a friend of the Autiers. The brother was Guilhem de Rodes; the alleged spy was Raimond de Rodes. Is this true? demanded the frightened Raimond. Have you had contact with the heretics? No, replied Guilhem de Rodes. The beguin is a liar.

This was itself a lie. Guilhem de Rodes had first met the heretics in the spring of 1298. He had listened to their preaching, had given them food and shelter, and was in fact related to them: they were his uncles. The Autiers had recently returned from Lombardy, having previously been notaries working for the small villages and towns around the Ariege river. In Lombardy they had converted to the Cathar faith, which had been dominant in southern France during the thirteenth century, but had died out in more recent years under the attentions of the inquisitors. Pierre and Guilhem Autier were to start a revival.

Catharism was a Christian heresy. Those who held the Cathar faith called themselves Good Christians and believed that they were the true inheritors of the mission of the apostles. They also believed that there were two Gods: a Good God, who created the spirit, and a Bad God who created all corporeal matter. This dualist belief was antithetical to Roman Catholic orthodoxy; and in any case, the Cathars believed that the Roman Catholic Church was corruptthe Whore of Babylon they called it. In the early thirteenth century there were several thousand Cathars, and many more believers, in the south of France. By the early fourteenth century, however, only fourteen Cathars survived, largely hidden in the Pyrenean villages. Nonetheless, such beliefs were not tolerated by the orthodox powers. Hence the eagerness of the Dominicans at Pamiers to take the opportunity to capture the Autiers. Hence too the danger that Guilhem Djean posed to the de Rodes brothers.

Next page