HOUGHTON MIFFLIN HARCOURT

BOSTON NEW YORK 2011

Copyright 2011 by Jonathan Wright

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wright, Jonathan, date.

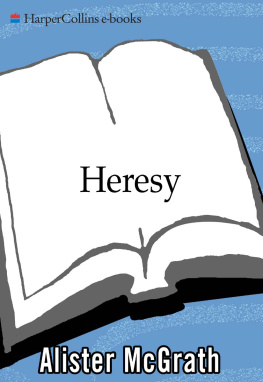

Heretics : the creation of Christianity from the Gnostics to the modern

church / Jonathan Wright.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-15-101387-6

1. Christian hereticsHistory. 2. Christian heresiesHistory.

3. Church history. I. Title.

BT 1315.3. W 75 2011

273dc22 2010043049

Printed in the United States of America

DOC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Peter Taylor

Contents

1. T HE H ERETICS

2. T HE I NVENTION OF H ERESY

3. C ONSTANTINE , A UGUSTINE, AND THE

C RIMINALIZATION OF H ERESY

4. T HE H ERESY G AP

5. M EDIEVAL H ERESY I

6. M EDIEVAL H ERESY II

7. R EFORMATIONS

8. T HE D EATH OF H ERESY?

9. A MERICAN H ERESY

10. T HE P OLITE C ENTURIES

11. C ONCLUSION

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTES

SUGGESTED READING

INDEX

1. The Heretics

O VER THE PAST two thousand years Christian heretics have been likened to whores and lepers, savage beasts and demons, sexual perverts and child killers. So far as the sixteenth-century Jesuit Francis Coster was concerned, they had a great deal in common with "the filthy dregs that flowed through the outhouse." Warming to his theme, Coster added that just as phlegm was expelled from the body, so heretics were to be banished from "the heavenly body of saints ... as if religion became sick and vomited them out."

Behind the unsavory rhetoric there was often an assumption that heresy ought to be obliterated. It was not simply pesky, it was utterly pernicious and, as a character in Thomas More's A Dialogue Concerning Heresies opined, it was the obligation of the righteous "to sit upon the mountains treading heretics under our feet like ants."

Sometimes God was touted as the chief executioner. Stories would be told of the fourth-century heresiarch Arius (about whom we'll hear much more) going to the lavatory one day only to witness his bowels gushing out. Into which disgusting mess, so Saint Ambrose reported, his head fell "headlong, besmirching those foul lips with which he had denied Christ." This, Ambrose crowed, was no random accident, no "chance manner of death." It was the Almighty inflicting vengeance upon "wickedness."

Sometimes, the ant treading was left to human beings, as when hundreds of medieval Cathars were slaughtered by crusading armies at Bziers in 1209; or when (so legend tells) North African Donatists were herded onto ships at Carthage in 347, weighed down with casks of sand, and dumped far out at sea; or when poor old Giulio Cesare Vanini's tongue was cut out ahead of his being strangled at the stake in 1619 Toulouse. Many heretics made it through the vale of tears unharmed, but this did not necessarily exempt them from punishment. They could be condemned after death, at which time their bones would be dug up and destroyed or, like the sixty-seven deceased heretics in Mexico in 1649, be burned in effigy.

These were not the only sanctions available to the syndics of orthodoxy, however, and the historical landscape of heresy is not nearly as corpse-strewn as might be imagined. From the perspective of the ecclesiastical establishment, to kill a heretic was to fail. The murdered heretic was someone who, despite all the threatening and cajoling, had obstinately refused to recant his errors. Worse yet, he could look a lot like a righteous martyr to his followers and confreres. It was far preferable, therefore, to win supposedly errant Christians back to the supposedly true path by means of corrective justice. This, in terms of theological logic, was deemed to be charitable (you were only trying to save people from eternal perdition, after all). If this was caritas, however, it was often of an extravagant, sometimes brutal variety.

Medieval heretics were made to go on penitential pilgrimages (often in chains), their clothes were bedecked with stigmatizing, stitched-in symbols, and they were sentenced to grueling service in the king's galleys. In sixteenth-century France they could be whipped or made to endure the most public humiliations: standing in their penitential gowns in the church or the public square, bareheaded and shoeless, holding a lighted candle, abjuring their errors, and begging the community for forgiveness. If they were errant clerics, their heads might be shaved (removing all sign of their tonsure), their priestly vestments ceremonially stripped off, or, if they were especially unlucky, their flesh cut from the thumb and index finger: a symbolic way of removing their right to celebrate the Eucharist.

An obvious question springs to mind. What was this thing called heresy and why was it so detested? To indulge in such lavish persecutory measures must surely have required a great deal of certainty on the part of those doing the persecuting.

An important first step was to define this most heinous of crimes: it had to be identified before it could be stamped out. An awful lot of theological ink was spilled in this pursuit but, for our present purposes, a sentence from the medieval theologian Robert Grosseteste is as good a starting point as any. Heresy, he wrote, is "an opinion chosen by human perception, contrary to Holy Scripture, publicly avowed and obstinately defended." At first blush, this looks fairly straightforward but, once it is unpacked, the definition turns out to be quite sophisticated. Religious truth, so the theory went, was divinely inspired, objective, and fixedsoaring far above the fleeting speculations of human opinion. There was room for reined-in theological interpretation (at least for learned clerics), the variable nuts and bolts of worship could sometimes be tinkered with, and some concepts and rituals might take several centuries to emerge. When it came to basic Christian dogmas, however, these were all contained within the New Testament message. They had been righteously pored over by the fathers of the early church and codified in a succession of creedal statements, church councils, and, so far as the Western half of Christendom was concerned, papal pronouncements.

There was no good excuse for any reasonably well informed Christian to dissent from these supposedly eternal verities. To do so was to threaten the unity of Christendom: it was to trample on the memory and sacrifice of Christ. Heretics often advertised themselves as holy men but, so far as the church was concerned, they were madmen, prideful scoundrels addicted to the exercise of their addled imaginations, or, more than likely, the minions of Satan.

Grosseteste's talk of public avowal is also crucial. The heretical mind in which dangerous thoughts secretly festered was beyond the reach of the church militant. There had always been vipers in the nest: hypocrites and dissemblers who harbored heretical opinions. It didn't really matter. God could tell the difference and would deal with such wretches accordingly. In the here and now, so long as the heretic did not spout his blasphemies in the street, the tavern, or the pew, then others were not at immediate risk of infection.

Obstinacy, another of Grosseteste's keywords, was just as important. There was no need to rush to judgment when confronted with a seemingly heretical deed or utterance. To be guilty of full-fledged heresy a person had to be aware that his behavior contradicted orthodoxy, and he had to persist in that behavior. The theological term for this is pertinacity. Often, the suspected heretic might simply have been acting out of ignorance, confusion, or habit. Perhaps he was brought up by heretical parents and had never been exposed to what the established church regarded as pure doctrine. The obvious litmus test for distinguishing between unintentional and willful heresy was to inform the supposed heretic of the church's acceptable teachings and see how he reacted. If he agreed to conform, then that, after the exaction of suitable penances, was usually the end of the matter. If, however, he clung to his heterodox notions, then the more gruesome punishments could be unleashed.

Next page