ALSO BY STANISLAS DEHAENE

Reading in the Brain

The Number Sense

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2014

Copyright 2014 by Stanislas Dehaene

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Excerpt from Kinds of Minds: Toward an Understanding of Consciousness by Daniel Dennett. Copyright 1996 by Daniel Dennett. Reprinted by permission of Basic Books, a member of the Perseus Books Group.

Definition of consciousness from The International Dictionary of Psychology by N. S. Sutherland (Continuum, 1989; Crossroad, 1996).

Illustration credits appear .

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Dehaene, Stanislas.

Consciousness and the brain : deciphering how the brain codes our thoughts / Stanislas Dehaene.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-698-15140-6

1. Consciousness. 2. Brain. 3. Cognitive neuroscience. I. Title.

QP411.D44 2014

612.8'2dc23

2013036814

Version_1

To my parents, and to Ann and Dan, my American parents

Consciousness is the only real thing in the world

and the greatest mystery of all.

Vladimir Nabokov, Bend Sinister (1947)

The brain is wider than the sky,

For, put them side by side,

The one the other will include

With ease, and you beside.

Emily Dickinson (ca. 1862)

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION: THE STUFF OF THOUGHT

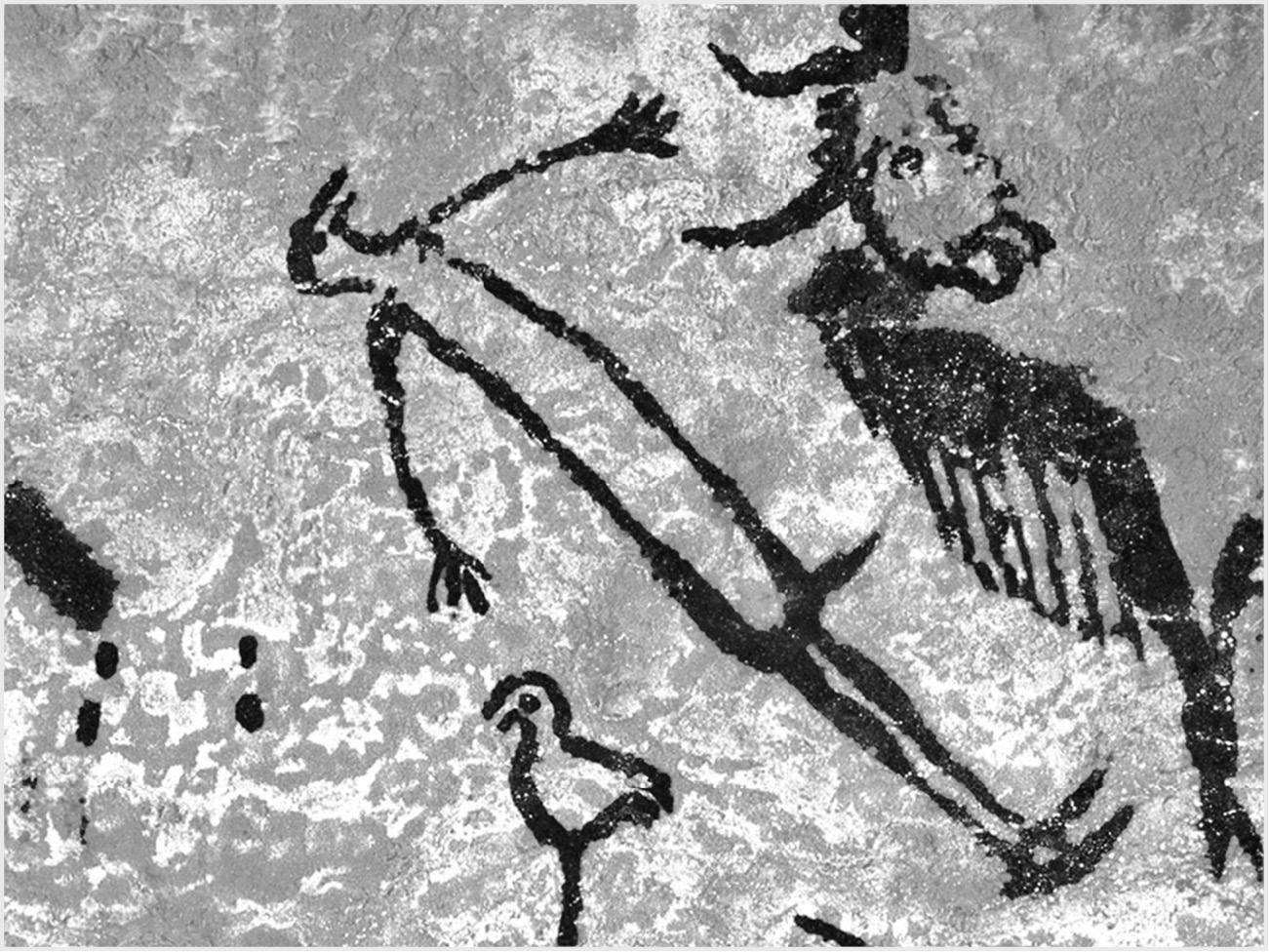

D eep inside the Lascaux cave, past the world-renowned Great Hall of the Bulls, where Paleolithic artists painted a colorful menagerie of horses, deer, and bulls, starts a lesser-known corridor known as the Apse. There, at the bottom of a sixteen-foot pit, next to fine drawings of a wounded bison and a rhinoceros, lies one of the rare depictions of a human being in prehistoric art (). The man is lying flat on his back, palms up and arms extended. Next to him stands a bird perched on a stick. Nearby lies a broken spear that was probably used to disembowel the bison, whose intestines are hanging out.

FIGURE 1. The mind may fly while the body is inert. In this prehistoric drawing, dated approximately 18,000 years ago, a man lies supine. He is probably asleep and dreaming, as hinted by his strong erection, characteristic of the phase of rapid-eye-movement sleep, during which dreams are most vivid. Next to him, the artist painted a disemboweled bison and a bird. According to the sleep researcher Michel Jouvet, this may be one of the first depictions of a dreamer and his dream. In many cultures, the bird symbolizes the minds ability to fly away during dreamsa premonition of dualism, the misguided intuition that thoughts belong to a different realm from the body.

The person is clearly a man, for his penis is fully erect. And this, according to the sleep researcher Michel Jouvet, illuminates the drawings meaning: it depicts a dreamer and his dream. As Jouvet and his team discovered, dreaming occurs primarily during a specific phase of sleep, which they dubbed paradoxical because it does not look like sleep; during this period, the brain is almost as active as it is in wakefulness, and the eyes ceaselessly move around. In males, this phase is invariably accompanied by a strong erection (even when the dream is devoid of sexual content). Although this weird physiological fact became known to science only in the twentieth century, Jouvet wittily remarks that our ancestors would easily have noticed it. And the bird seems the most natural metaphor for the dreamers soul: during dreams, the mind flies to distant places and ancient times, free as a sparrow.

This idea might seem fanciful were it not for the remarkable recurrence of imagery of sleep, birds, souls, and erections in the art and symbolism of all sorts of cultures. In ancient Egypt, a human-headed bird, often depicted with an erect phallus, symbolized the Ba, the immaterial soul. Within every human being, it was said, dwelled an immortal Ba that upon death took flight to seek the afterworld. A conventional depiction of the great god Osiris, eerily similar to Lascauxs Apse painting, shows him lying on his back, penis erect, while Isis the owl hovers over his body, taking his sperm to engender Horus. In the Upanishads, the Hindu sacred texts, the soul is similarly depicted as a dove that flies away at death and may come back as a spirit. Centuries later doves and other white-winged birds came to symbolize the Christian soul, the Holy Spirit, and the visiting angels. From the Egyptian phoenix, symbol of resurrection, to the Finnish Sielulintu, the soul bird that delivers a psyche to newborn babies and takes it away from the dying, flying spirits appear as a universal metaphor for the autonomous mind.

Behind the bird allegory stands an intuition: the stuff of our thoughts differs radically from the lowly matter that shapes our bodies. During dreams, while the body lies still, thoughts wander into the remote realms of imagination and memory. Could there be a better proof that mental activity cannot be reduced to the material world? That the mind is made of a distinct stuff? How could the free-flying mind ever have arisen from a down-to-earth brain?

Descartess Challenge

The idea that the mind belongs to a separate realm, distinct from the body, was theorized early on, in major philosophical texts such Platos Phaedo (fourth century BC) and Thomas Aquinass Summa theologica (126574), a foundational text for the Christian view of the soul. But it was the French philosopher Ren Descartes (15961650) who explicitly stated what is now known as dualism: the thesis that the conscious mind is made of a nonmaterial substance that eludes the normal laws of physics.

Ridiculing Descartes has become fashionable in neuroscience. Following the publication of Antonio Damasios best-selling book Descartes Error in 1994, many contemporary textbooks on consciousness have started out by bashing Descartes for allegedly setting neuroscience research years behind. The truth, however, is that Descartes was a pioneering scientist and fundamentally a reductionist whose mechanical analysis of the human mind, well in advance of his time, was the first exercise in synthetic biology and theoretical modeling. Descartess dualism was no whim of the momentit was based on a logical argument that asserted the impossibility of a machine ever mimicking the freedom of the conscious mind.