REDISCOVERED RECIPES FOR CLASSIC BREWS

DATING FROM 1800 TO 1965

Ron Pattinson

CONTENTS

Recipes

Recipes

Recipes

Recipes

Recipes

Recipes

Recipes

Recipes

Recipes

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTIONI ve been fascinated by historic beers ever since I first saw an old Batemans brewery mirror advertising the exotic products of yesteryear. Later, when looking at old labels, I wondered what the beers behind them had been like. For a long time, it seemed tasting these beers would remain an unfulfilled dream.

Then I realized that far from being lost, the details of these beers had been carefully stored in archives and brewery store rooms across Britain. Discovering the secrets of these lost beers was a possibility. All that was required was a bit of effort and determination.

Just how much effort, I was luckily unaware of at the start of my journey into beers past. I say luckily because, had I realized how much of my time it would devour, I might never have started. Days spent arched over dusty Whitbread records at the London Metropolitan Archives, snapping away crazily like a hyperactive paparazzi. Weeks consumed in puzzling over scrawly handwriting and incomprehensible abbreviations. Worth it in the end, to learn just how they had brewed in the past.

There were many surprises in the course of my research. The past turned out to be a far more complex and dynamic place than I had imagined. Every generation had its own beer and its own way of brewing them.

But dusty records will tell you only so much. All that dust left me with a roaring thirsta thirst for the beers of the past. Happily, there were brewers who shared my thirst for history and were keen to brew the recipes Id unearthed. Menno Olivier at De Molen, John Keeling and Derek Prentice at Fullers, and Dann Paquette at Pretty Things made my dreams come true.

I started my blog, Shut up About Barclay Perkins (the name comes from a common complaint of my children, fed up with hearing endless trivia about London brewer Barclay Perkins), to publish what Id discovered about Britains brewing history and was delighted to learn that others shared my enthusiasm.

Now its time to assemble what Ive learned and make it available to home brewers in an easily digestible form. This book describes the development of the major British styles between 1800 and 1965 along with recipes to allow you to brew typical beers from the whole of that period. This is when the styles that dominate modern craft brewing took form: IPA, porter, stout, and barley wine. As an extra-special treat, Ive thrown in a few extinct German beer styles.

I hope you enjoy reading what follows, brewing the beers, and drinking them. Because when it comes down to it, beer is all about the pleasure of drinking a delicious pint. That its a beer your grandfather might have drunk only adds to the fun.

Ron Pattinson,

21st March 2013, Amsterdam

B eer has four basic ingredients: malt, water, hops, and yeast. The malt provides the sugars, which the yeast ferments into alcohol. The hops add beers distinctive bitter note.

For much of the period covered by this book, those four ingredients, and sometimes sugar, were the only ingredients allowed by law. It was only in 1880 that the law was liberalized and adjuncts such as corn and rice were allowed as alternative sources of fermentable material.

MALT

MALTM alt is produced by fooling barley into germinating and then stopping the process before the grain sprouts by drying it in a kiln. This starts the conversion of the starches in the grain into sugar that yeast can ferment.

Historically, far fewer types of malt were available than today. In the first half of the nineteenth century, only five types were used: pale malt, white malt, amber malt, brown malt, and black malt. Crystal malt was developed quite early in the nineteenth century but came into common use only in the twentieth century.

Britain was unable to grow enough grain for either bread making or brewing purposes from the middle of the 1800s onward. Large quantities of barley were imported, but it was always malted in Britain. It made sense, as British malting technology was the best in the world. Much came from North America, particularly California, but many other regions also supplied grain, such as the Middle East, Australia, Chile, and continental Europe.

Brewers liked to use a mix of British two-row barley malt and foreign six-row barley malt and got all upset when the world wars interrupted the supply of California barley.

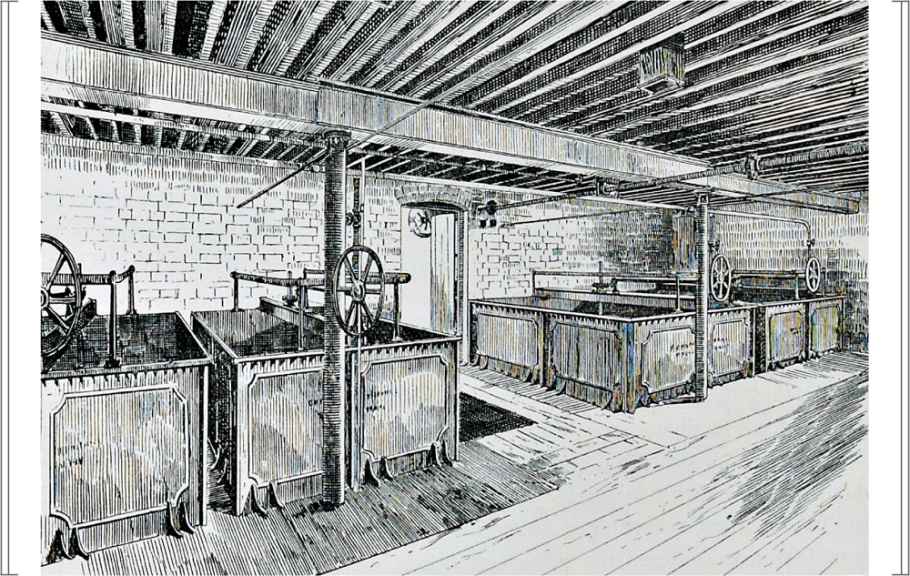

The steeping tanks at Moor Head Maltings, Cardiff

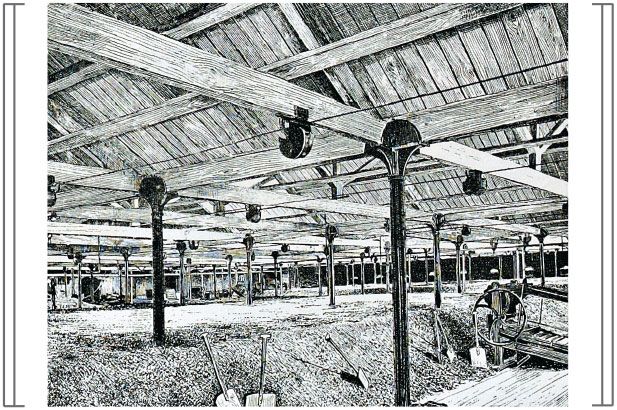

The barley floor at Allsopp

Pale malt

Pale malt first evolved around 1600, when maltsters in the Midlands began to kiln using coke, a type of coal with impurities such as sulfur removed, as a fuel. The extra control possible with this fuel allowed a reliably pale malt to be produced. Starting as an expensive novelty, its use exploded in the late eighteenth century when brewers discovered, through the use of the hydrometer, how much higher yieldingand hence more economicalit was than other base malts. By 1800, pretty much every type of beer used pale malt as its base.

The need for high-quality pale malt for pale ale brewing led to the evolution of a specific kind of malt, pale ale malt. It was made from top-quality barley and kilned as pale as possible. The best substitute for this is the best modern British pale malt. Though not Maris Otterthats usually kilned too dark.

The palest type of pale malt was sometimes called white malt.

Brown malt

Brown malt is a tricky devil to pin down. It has been made in many different ways and had many different characters over the years.

In the eighteenth century, it was diastatic; that is, the grains contained sufficient enzymes to convert their starch into sugar, and it was regularly used as a base malt. The earliest porters and stouts were brewed from 100 percent brown malt. London brewers usually purchased their malt from Hertfordshire, just north of London. There, it was the custom to use straw as a fuel in the final stage of the kilning, where the temperature was increased dramatically. In other areas, different fuels were used, and these had a big impact on the flavor of the malt.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION