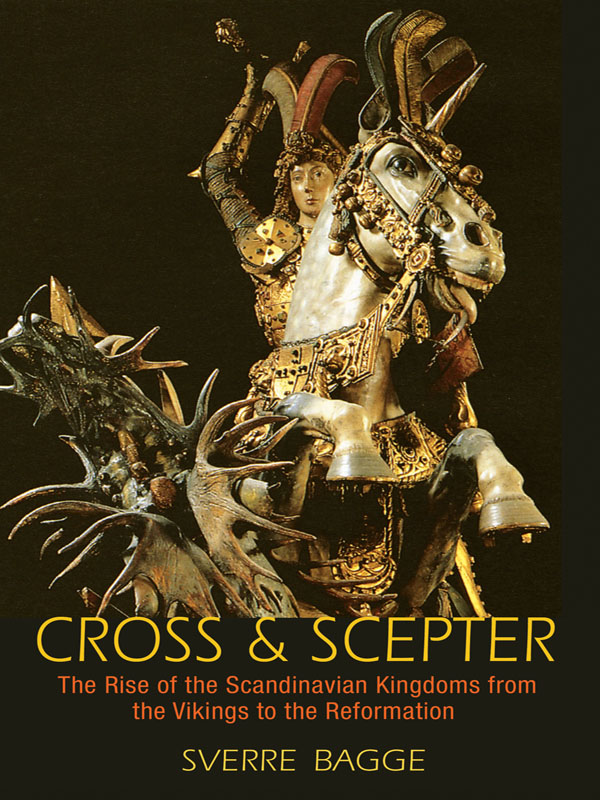

CROSS AND SCEPTER

CROSS & SCEPTER

The Rise of the Scandinavian Kingdoms from the Vikings to the Reformation

SVERRE BAGGE

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

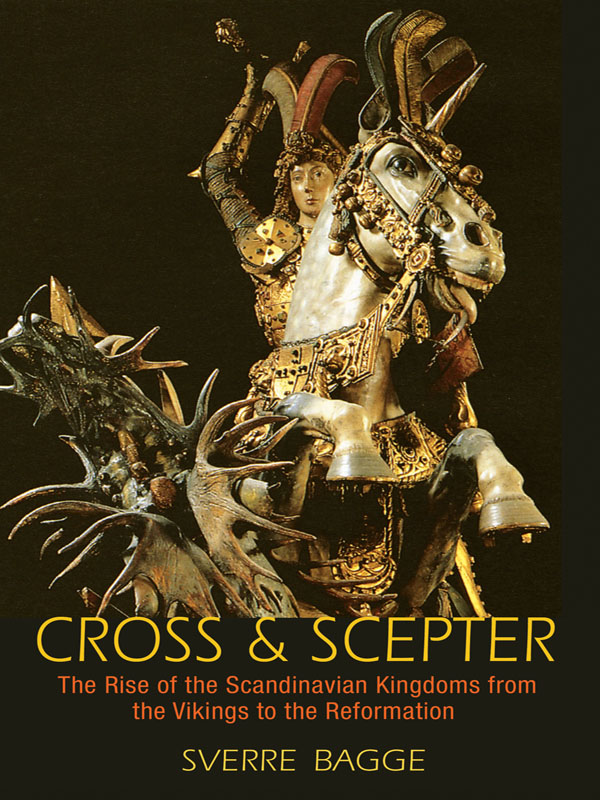

Jacket Art: Berndt Notke, Saint George and the Dragon (detail), 1489, sculpture group in the Great Cathedral of Stockholm, Sweden.

Photo: Anders Qwarnstrm

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bagge, Sverre, 1942

Cross and scepter : the rise of the Scandinavian kingdoms from the Vikings to the Reformation / Sverre Bagge.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-16150-1 (hardcover : acid-free paper) 1. ScandinaviaHistory. 2. Middle Ages. 3. ScandinaviaKings and rulersHistory. 4. ScandinaviaPolitics and government. 5. ChristianityScandinaviaHistoryTo 1500. 6. MonarchyScandinaviaHistoryTo 1500. 7. Aristocracy (Political science)ScandinaviaHistoryTo 1500. 8. ScandinaviaSocial conditions. 9. Social changeEuropeCase studies. I. Title.

DL49.B34 2014

948'.023dc23 2013040063

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Garamond Premier Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

CONTENTS

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THIS BOOK HAS ITS BACKGROUND in my period as the director of two research centers, the Centre for Medieval Studies at the University of Bergen (200212) and the Nordic Centre for Medieval Studies at the Universities of Bergen, Gothenburg, Odense, and Helsinki (200510), funded by grants respectively from the Norwegian Research Council and the Joint Committee for Nordic Research Councils for the Humanities and the Social Sciences. I thank my many colleagues in these milieus for pleasant company and a stimulating exchange of ideas. I am particularly grateful to Thomas Lindkvist, Bjrn Poulsen, and Jrn yrehagen Sunde, and to two anonymous readers who have read the manuscript and given useful suggestions, and to Ola Snden for his work with the illustrations. I also want to thank Patrick Geary for his interest in the book while acting as a board member of the Nordic Centre and for bringing me in touch with Princeton University Press. Once that contact was established, it was a pleasure to work with Brigitta van Rheinberg and her colleagues, who have combined enthusiasm, speed, and thoroughness in a most impressive way. I also thank the Oxford University Press for permission to use extracts from the Oxford History of Historical Writing, volume 2: 4001400, edited by Sarah Foot and Chase F. Robinson (2012), Stanford University Press for permission to use the translation from Ljsvetninga Saga on p. 1, and the Museum Tusculanum Press, Copenhagen, for permission to use material published in my book From Viking Stronghold to Christian Kingdom: State Formation in Norway, c. 9001350 (Copenhagen, 2010).

Sverre Bagge

Bergen, September 2013

CROSS AND SCEPTER

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

And when the tables were set, Ofeig put his fist on the table and said, How big does that fist seem to you, Gudmund?

Big enough, he said.

Do you suppose there is any strength in it? asked Ofeig.

I certainly do, said Gudmund.

Do you think it would deliver much of a blow? asked Ofeig.

Quite a blow, Gudmund replied.

Do you think it might do any damage? continued Ofeig.

Broken bones or a deathblow, Gudmund answered.

How would such an end appeal to you? asked Ofeig.

Not much at all, and I wouldnt choose it, said Gudmund.

Ofeig said, Then dont sit in my place.

IN THIS STORY FROM the Icelandic Ljsvetninga Saga, power is concentrated in a big fist in a way that recalls Hobbess characterization of primitive man, whose life is solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. There is constant competition and the physically strongest is likely to win, as in the competition for leadership among animals.

With increasing institutionalization, physical power is replaced by legitimate birth, specific qualifications, or formal election, and the fist by symbols of authority. Such symbols no doubt existed in Scandinavia from early on, but they assumed particular importance with the introduction of Christianity and the formation of kingdoms; in other words, with the introduction of the cross and the scepter. Bishops and archbishops were elected and consecrated and wore miters, staffs, rings, and crosses as signs of their dignity. Kingship eventually followed a similar path, the office being filled according to formal rules and by an incumbent who wore a crown and scepter. These leaders in turn had representatives of lower rank, who were supposed to carry out their commands. In theory, although not necessarily in practice, open competition was replaced by a formal hierarchy that was believed to have been instituted by God. Thus, from the tenth century onwards, a new concept of government and public authority was introduced to Scandinavia.

Can we use the term state formation when speaking of the Middle Ages? The term state is used in a different sense in different disciplines. While social scientists, particularly social anthropologists, are inclined to use the term when referring to any kind of lordship over larger areas or numbers of people, in some cases qualifying it as an early state, historians often have stricter criteria. One of these has been the word itself. The Latin status (condition, state) derived from the combination status rei publicae, which was current in the Middle Ages, began to be used from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century on as a technical term, meaning state in the modern sense. This terminological change is understood as expressing a new understanding of the state as an institution existing independently of the person or persons governing it, an understanding that incorporates the classical definitions of the state as a monopoly on violence or an impersonal and bureaucratic government. Although the importance of such a terminological change should not be underestimated, it can hardly be regarded as decisive; a new name does not mean that the phenomenon in question cannot have existed before. In practice, res publica in the Middle Ages may have had at least some of the impersonal connotations associated with the early-modern status.

In the present context, I regard the terminological question mainly as a practical one. The great divide in Scandinavian history was the formation of the three kingdoms, two of which have continued to exist until the present, while the third, Norway, preserved enough of its identity under Danish dominance to reemerge as an independent unit in 1814. It would thus seem natural to use the term state for these kingdoms from this date on, despite the rudimentary character of their political institutions. The most important concept in the following, however, is state formation, which is a relative concept, implying centralization, bureaucratization, the development of jurisdiction, a monopoly or near monopoly on violence, and so forth, for it is more critical to decide whether a process is heading in this direction than to decide exactly how many of these criteria must be present before it is allowable to use the word state. The following discussion will deal with the changes that took place in Scandinavia from the formation of the kingdoms in the tenth century until the end of the Kalmar Union and the introduction of the Reformation in the early sixteenth century, and with how the three Scandinavian kingdoms compared with other countries at the time in terms of stateness.

Next page

CONTENTS

CONTENTS