After HEGEL

After H EGEL

GERMAN PHILOSOPHY, 18401900

FREDERICK C. BEISER

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton & Oxford

COPYRIGHT 2014 BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PUBLISHED BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

IN THE UNITED KINGDOM: PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

PRESS.PRINCETON.EDU

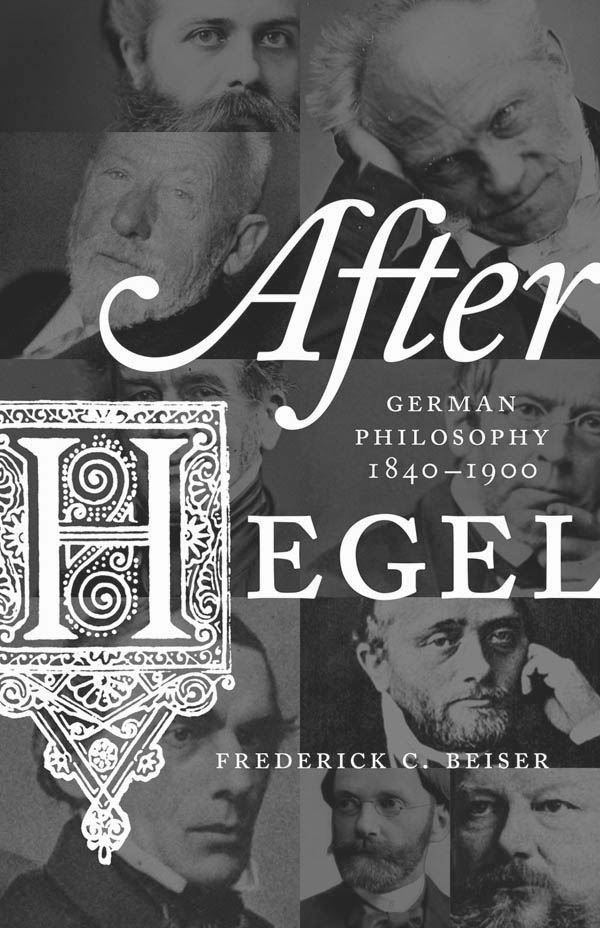

Jacket Images: Image of Karl Robert Eduard von Hartmann from the Benjamin R. Tucker Papers/Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library, MssCol3040; Image of Eugen Dhring from Eugen Karl Dhring, Dhring-wahrheiten: in Stellen aus den Schriften des Reformators, Forschers und Denkers, nebst descend Bildniss. T. Thomas, 1908; Image of Hermann Lotze from Richard Falckenberg, Hermann Lotze. Stuttgart, 1901; Image of Friedrich Adolf Trendelenburg from a photo album owned by the Mathematische Gesellschaft (Hamburg), Oberwolfach Photo Collection, Archives of the Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach gGmbH (MFO).

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Beiser, Frederick C., 1949

After Hegel : German philosophy, 1840-1900 / Frederick C. Beiser.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-691-16309-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 0-691-16309-X (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Philosophy, German19th century. I. Title.

b3181.b45 2014

193dc23

2013050419

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA IS AVAILABLE

This book has been composed in Adobe Caslon Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

for MICHAEL MORGAN

CONTENTS

PREFACE

The second half of the nineteenth century in Germany was one of the most creative and revolutionary periods of modern philosophy. It has been, however, little studied in German, even less in English. The aim of this book is to introduce the Anglophone reader to the philosophy of this period. To ensure wide historical coverage, and to maintain a philosophical focus, the book is organized according to controversies rather than themes or thinkers.

There is no pretension to completeness in this work. I claim only to have introduced the Anglophone reader to five major controversies of the period. In discussing any one of these controversies much more could have been said; but for reasons of space I had to be selective about which material is most important and interesting. There were other major controversies in the period; but even an adequate treatment of their main episodes would have gone beyond either my word limit or my time frame. A proper discussion of the crisis of historicism, or the debate between logicism and psychologism, would have taken me well into the twentieth century.

While I have been severe in setting myself stopping points, I have been more liberal about starting points. In some cases a full understanding of a controversy required treating its origins before 1840, and in those cases I could not so easily restrict myself.

All translations from the German are my own. Because almost all of the writings cited in this book are untranslated, all titles appear in the original German. For the sake of consistency, even translated works are left in the original.

For the stimulus to write this book I am very much indebted to Rob Tempio, philosophy editor of Princeton University Press, who proposed to me the idea of a short history of nineteenth-century philosophy in the spring of 2013. For the encouragement to write it, and other books, I am especially grateful to my friend Michael Morgan, to whom this book is dedicated.

SYRACUSE, NEW YORK

November 2013

After HEGEL

INTRODUCTION

1. A REVOLUTIONARY HALF CENTURY

This book is about German philosophy from 1840 to 1900. All periodizations are artificial, and this one is no exception. But there are still good reasons for choosing these dates. 1900 is the beginning of a new century, one more complex, tragic, and modern than any preceding it. 1840 is significant because it marks both an end and a beginning. It is the end of the classic phase of Hegelianism, whose fortunes were tied to the Prussian Reform Movement, which came to a close in 1840 with the deaths of Friedrich Wilhelm III and his reformist minister Baron von Altenstein. settling his accounts with Hegelianism and initiating a new materialist-humanist tradition in philosophy.

The chief focus of this book is, therefore, German philosophy in the second half of the nineteenth century. It is an unusual topic, since most books on German philosophy in the nineteenth century concentrate on the first half century. And with good reason. The first three decades of this century were some of the most creative in modern philosophy. They coincide with the formation and consolidation of the idealist tradition and with the growth and spread of Romanticism, two of the most influential intellectual movements of the modern era. By contrast, the second half of the century seems less creative and important. Idealism had fallen into decline, and Romanticism was a rapidly fading memory. No intellectual movements of comparable stature grew up to replace them.

The common opinion about German philosophy in the second half of the nineteenth century, even among German contemporaries, was that it was a period of decline and stagnation. The great creative age of idealism had passed away with Hegels death, it seemed, only to be succeeded by an age of realism, which was more concerned with empirical science and technical progress than philosophy. The little philosophy done in this periodso it was saidhad been conducted either by idealist epigones, who were not original, or by materialists, who were not really philosophers at all.

All this leaves us with the question: Why write about the second half of the century at all? What of philosophical significance transpired in this half century that it deserves to be treated in a monograph like this one? The short and simple answer to this question is that the common opinion is just false, and that the second half of the century, though written about much less, is more important and interesting philosophically than the first half. There are several reasons why this is so.

The second half of the nineteenth century was a period dominated by crises and controversies, whereas the first half was one of consolidation and consensus. The idealist and romantic traditions had already come into their own by the first years of the nineteenth century, and it was only a matter of establishing themselves in universities and the public consciousness. The decline of the idealist and romantic traditions by the 1840s, however, led to a period of disorder, confusion, and ferment. This disorder and confusion was also the womb of creativity and rebirth, the start of a new era of philosophy.

Normal times in philosophy are those when there is a settled and agreed definition of philosophy, when philosophers have a general consensus about the nature of their discipline and the tasks it involves. Revolutionary times are those when there is no such definition, when there are many conflicting conceptions of philosophy. Following these definitions, the late eighteenth, early nineteenth, and late twentieth centuries were normal times. The latter half of the nineteenth century, however, was revolutionary. For this was an age when there was no settled or agreed definition of philosophy, when there were many conflicting conceptions of the discipline. Philosophers asked themselves the most basic questions about their discipline: What is philosophy? How does it differ from empirical science? Why should we do philosophy? We will have occasion to examine some of the answers to these questions in .

Next page