This book is supported by the Institut franais as part of the Burgess programme (www.frenchbooknews.com)

This English-language edition published by Verso 2013

Translation Warren Montag 2013

First published as Identit et diffrence: Linvention de la conscience

ditions du Seuil 1998

Introduction Stella Sandford 2013

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-134-3 (pbk)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-135-0 (hbk)

eISBN (US): 978-1-78168-192-3

eISBN (UK): 978-1-78168-503-7

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v3.1

Contents

Preface to the English Edition

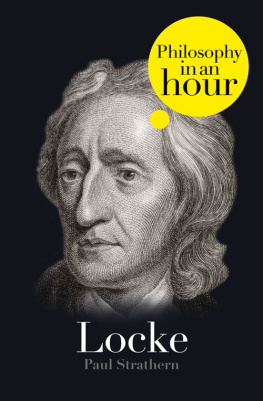

When Stella Sandford and Verso proposed an English edition of my work on Locke and the invention of consciousness essentially a commentary on Book II, Chapter XXVII of An Essay Concerning Human Understanding I was obviously very flattered at the idea that a historical, philosophical and philological text by a French scholar might be made available to, and submitted to the judgment of, Anglophone readers in the land of the author of the Essay himself. But I did not entirely anticipate all the difficulties that such an enterprise would entail, nor the degree to which I would have to depend on the indulgence of my new readers.

Part of the difficulty lies in the fact that my work was written nearly twenty years ago, in context of the 1990s, which means that much has been written since on Locke in general, and in particular on the theory of knowledge and the metaphysics of the subject contained in the Essay, and finally on his contribution to the puzzle of personal identity in English and in other languages. I thus will not have taken all of this into account (which is not to say that I was able even then to take into account all that had been written up to that point). This difficulty, however, was in part mitigated by the fact that my friend Stella Sandford agreed to take on the task of writing an original introduction to the work and urged me to complement the introduction with an afterword containing my own new reflections (a suggestion that, as will be seen, I preferred to take up in the form of bringing in a comparison with Spinoza, which had been frequently alluded to but remained essentially missing from the French original edition).

But the rather peculiar genre of the work, determined by the circumstances of its conception and publication, imposes an even greater difficulty. The core of the original French version of this text was the re-publication of Book II, Chapter XXVII of the Essay Concerning Human Understanding (Of Identity and Diversity), accompanied by two French translations: one from the seventeenth century by Pierre Coste, undertaken under Lockes own supervision, and which served to propagate the authors ideas not only in France but throughout Europe (as demonstrated by Leibnizs reliance on it in the New Essays in Human Understanding); and a new translation, with which I did not intend to replace the earlier one, but rather to show the breadth and meaning of the problems of conceptual translation associated with the European invention of consciousness (which I maintain takes place in philosophy primarily in the work of Locke, or at least changes direction on the basis of his oeuvre). This labour, which combined philology and philosophy (the first furnishing the materials for an experiment in the comparative semantics of the classical languages, while the second was essentially developed on the basis of an analysis of concepts

My book thus appeared as an assemblage of five parts of unequal length: 1) an introductory essay entitled Lockes Treatise on Identity, in which I took as my point of departure the theoretical symptom constituted by Pierre Costes explanation of the neologisms he was compelled to invent in order to translate Lockes key concepts (consciousness and self to which must also be added uneasiness). My aim was to develop a general interpretation of the epistemological break introduced by Locke, as well as of his place in the history of European philosophy; 2) a textual section in which I included first Costes translation (1700), and then opposite it Lockes original text (revised in accordance with Yolton and Nidditch), and finally my own retranslation; 3) a Glossary of the works key concepts, intended simultaneously to explore the difficulties of their translation and to expand their definition (by situating them in relation to philosophical debates, both classical and modern, whenever possible); 4) a complementary dossier of texts in a variety of languages (Latin, English and French), taken from Descartes, de la Forge, Malebranche, Cudworth, Rgis, Leibniz and Condillac, intended to outline the philosophical debates within which Lockes terms and statements must be situated in order for their strategic significance and function to become clear; and finally, a complementary bibliography. In the present edition, we have retained (in addition to the new texts referred to previously) my introductory essay (unchanged except for the correction of a few errors), and most of the entries in the Glossary (omitting those which may be considered minor, in that they discuss only technical questions of translation). Obviously, we have also omitted Lockes text itself, which English readers have at their disposal, as well as the two French translations (although with some regret, given that they would have been useful in providing the English reader with the experience of estrangement that would permit reader to reflect on the meaning of the concepts in his or her own language but the work had to be kept at a reasonable length), as well as the dossier of contemporary texts. Stella Sandford has provided a new bibliography.

I have recounted these details so that the reader can understand from the outset the form in which my argumentation developed, as much in the forms of argumentation) in a structural that is, differential fashion, granting all due importance to the materiality of writing and its idioms, which constitutes precisely the privileged link between these two aspects of a rigorous method in the history of philosophy.

Etienne Balibar, 2013

Barbara Cassin, ed., Vocabulaire europen des philosophies, Paris: ditions de Seuil, 2004.

It should be recalled that the translators notes were regarded as sufficiently important from a philosophical point of view to be themselves summarized or referred to in most of the scholarly editions of the Essay, in particular Nidditchs edition.

In French, unlike English or German, conscience and consciousness (or Gewissen and Bewusstsein) are signified by a single term,