Contents

Yoga Sutras

Text, translation and commentary

yogena cittasya padena vacaa

malaa sarirasya ca vaidyakena

yopakarottaa pravaraa muninaa

patajalia prajaliranatosmi

abahu Purusaakaraa

sankha cakrasi dharinam

sahasra sirasaa svetaa

pranamami patajalim

Let us bow before the noblest of sages, Patajali, who gave yoga for serenity and sanctity of mind, grammar for clarity and purity of speech, and medicine for perfection of health.

Let us prostrate before Patajali, an incarnation of Adisesa, whose upper body has a human form, whose arms hold a conch and a disc, and who is crowned by a thousand-headed cobra.

Where there is yoga, there is prosperity and bliss with freedom.

yastyaktva rupamadyaa prabhavati jagatonekadhanugrahaya praksinaklesarasirvisamavisadharonekavaktras subhogi sarvajanaprasutirbhujagaparikaras pritaye yasya nityaa devohisas sa vovyatsitavimalatanuryogado yogayuktas

Let us prostrate before Lord Adisesa, who manifested himself on earth as Patajali to grace the human race with health and harmony.

Let us salute Lord Adisesa of the myriad serpent heads and mouths carrying noxious poisons, discarding which he came to earth as single-headed Patajali in order to eradicate ignorance and vanquish sorrow.

Let us pay our obeisance to Him, repository of all knowledge, amidst His attendant retinue.

Let us pray to the Lord whose primordial form shines with pure and white effulgence, pristine in body, a master of yoga who bestows on us his yogic light to enable mankind to rest in the house of the immortal soul.

It is a remarkable accomplishment and a tribute to the continuity of human endeavour that today, some 2500 years after yoga was first described by the renowned Patajali, his living heritage is being commented upon and introduced to the modern world by one of yogas best exponents today, my own teacher B.K.S. Iyengar.

There are not many practical arts, sciences, and visions of human perfection of body, mind and soul which have been in practice over so long a period without attachment to a particular religious creed or catechism. Anyone can practise yoga, and this important contribution to the history of yoga and its validity today is for everyone.

YEHUDI MENUHIN

Patajalis Yoga Sutras are the bible of yoga. However, their inaccessibility in the hands of scholars and academics has left yoga practitioners adrift with neither chart nor compass. B.K.S. Iyengars translation, based on over fifty years of dedicated and accomplished practice and teaching, is unique in its relevance and utility to contemporary yoga practitioners. The depth of his practice and understanding shines through his elucidation of the often terse and obscure sutras. Iyengars ability to elucidate Patajali in pragmatic terms is an extension of his clarification of the subtlety and integrity of yoga practice. This is most evident in the rigorous precision with which he understands and articulates the body in yoga postures. However, it goes further and much deeper than that. In his unique investigation of alignment, Iyengar not only reveals the therapeutic necessity of stuctural integrity in the body, but also its subtle and equally necessary impact on the flow of energy and consciousness in the mind.

What Iyengar has proved, for those willing to apply themselves to test it, is that the apparent divide between matter and spirit, body and soul, and physical and spiritual is only that: apparent. Through his insistence on structural integrity he has opened the spiritual doorway to millions of people for whom the mind would otherwise never give up its subtleties. Here, in his presentation of Patajali, that door is flung wide open. This is especially clear, to even the least academically minded student, in his profound and practical interpretations of the sutras relating to Asana and pranayama. Here, especially, Iyengars genius comes as a great gift of clarity and insight that can only deepen the understanding and support the practice of any keen student.

Iyengars incomparable experience as an Indian teacher of Westerners, combined with his experience as a Brahmin and participant in a genuine lineage of the yoga tradition, gives his perspective an authority and authenticity that is all too often lacking. It offers a lucid and pragmatic interpretation of the insights and subtleties of yogas root guru. To practice yoga without the profound and panoramic inner cartography of the Yoga Sutras is to be adrift in a difficult and potentially dangerous ocean. To use that map without the compass of Iyengars deep and authoritative experience, is to handicap oneself unnecessarily. No yoga practitioner should be without this classic and invaluable work.

and Pronunciation

Sanskrit is an Indo-European language. It is ancient; the language of the Indian scriptures which claim to be eternal. They were recited or chanted in Sanskrit thousands of years ago, and still are today.

The word Sanskrit itself means perfect, perfected, literary, polished. It is a highly organized language, with a complex grammar. However, some works are written in a simpler form which it is not so difficult for us to grasp. To these types of work belong the Bhagavad Gita, the Upanisads , and also the Yoga Sutras of Patajali.

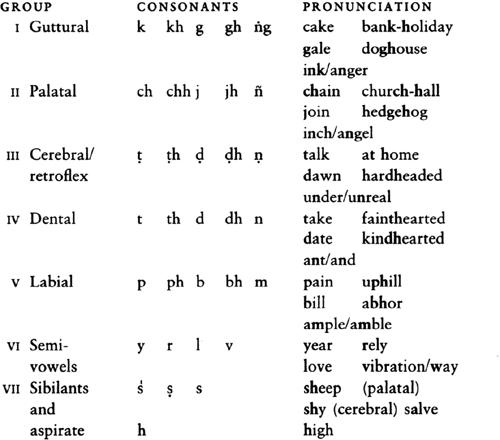

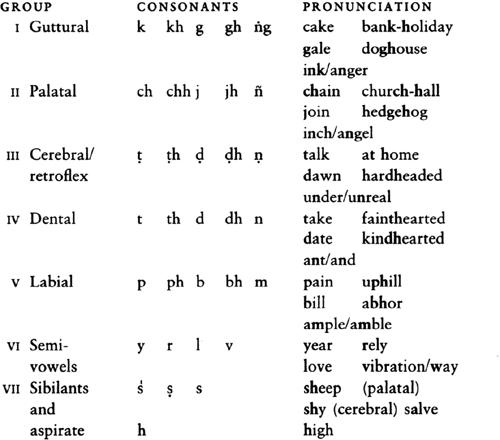

Sanskrit letters, both vowels and consonants, are arranged consecutively according to their organ of pronunciation, starting with throat (guttural), then palate (palatal), then a group of sounds called cerebral (modern retroflex, which may not originally belong to the Indo-European group), then dental and labial. After that come semi-vowels, sibilants, and a full aspirate. Philologists have given these sounds various names, but we are giving the approximate equivalent of their Sanskrit meanings.

These placings apply to vowels and to consonants.

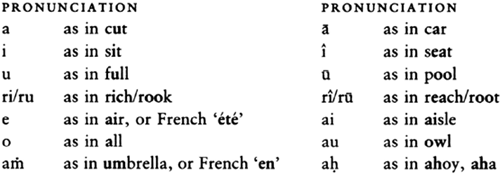

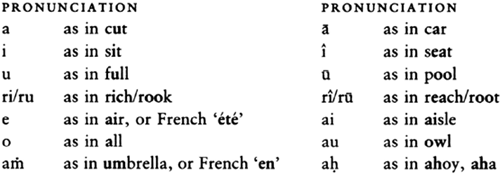

The following is a list of vowels, which includes diphthongs, a nasal (half n sound) and an aspirate (h sound). The vowels are short and long, the diphthongs long. The aspirate sound repeats its preceding vowel, (e.g. a: = aha, i: = ihi, etc.):

The following are the consonants and semi-vowels. The first five groups consist of 1) a leading hard consonant, 2) its aspirated form, 3) a corresponding soft consonant, 4) its aspirated form, and 5) its nasal consonant.

The following should be noted:

1) The h sound of the aspirated consonants should always be pronounced.

2) To pronounce the sounds in the cerebral group, the tongue is curled back (retroflexed) and the roof of the palate is then hit with the back of the tip of the tongue.

3) The dental group is similar to English, only the tongue touches the back of the teeth in pronouncing them.