About the Author

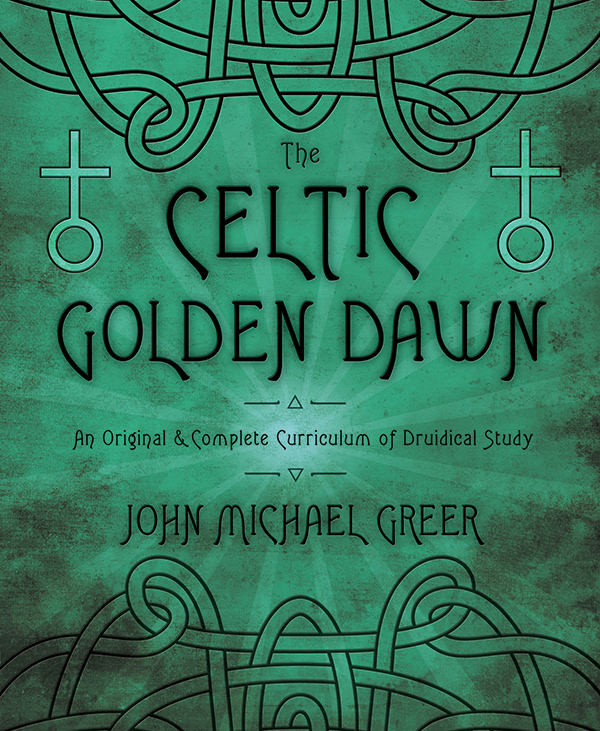

john michael greer (western Maryland) has been a student of occult traditions and the unexplained for more than thirty years. A Freemason, a student of geomancy and sacred geometry, and a widely read blogger, he is also the author of numerous booksincluding Monsters , The New Encyclopedia of the Occult, and Secrets of the Lost Symbol and currently serves as the Grand Archdruid of the Ancient Order of Druids in America (AODA), a contemporary school of Druid nature spirituality. Greer has contributed articles to Renaissance Magazine , Golden Dawn Journal , Mezlim , New Moon Rising , Gnosis , and Alexandria .

Llewellyn Publications

Woodbury, Minnesota

Copyright Information

The Celtic Golden Dawn: An Original & Complete Curriculum of Druidical Study 2013 by John Michael Greer

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any matter whatsoever, including Internet usage, without written permission from Llewellyn Publications, except in the form of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

As the purchaser of this e-book, you are granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. The text may not be otherwise reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or recorded on any other storage device in any form or by any means.

Any unauthorized usage of the text without express written permission of the publisher is a violation of the authors copyright and is illegal and punishable by law.

First e-book edition 2013

E-book ISBN: 9780738731773

Book design and edit by Rebecca Zins

Celtic knot: iStockphoto.com/Trudy Karl

Cover design by Kevin R. Brown

Interior illustrations by John Michael Greer

Llewellyn Publications is an imprint of Llewellyn Worldwide Ltd.

Llewellyn Publications does not participate in, endorse, or have any authority or responsibility concerning private business arrangements between our authors and the public.

Any Internet references contained in this work are current at publication time, but the publisher cannot guarantee that a specific reference will continue or be maintained. Please refer to the publishers website for links to current author websites.

Llewellyn Publications

Llewellyn Worldwide Ltd.

2143 Wooddale Drive

Woodbury, MN 55125

www.llewellyn.com

Manufactured in the United States of America

Table of Contents

: The Golden Dawn and the Celtic Twilight

Introduction

The Golden Dawn and the Celtic Twilight

the foundation of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in 1888 marked the zenith of one of the most creative periods in the long history of occultism and the convergence of trends that had been building in British and European occult circles for many decades. Too many students of occultism these days, whether they believe that the Golden Dawn system was handed down from the immemorial past or think that it was patched together more or less at random out of scraps of forgotten lore from the collections of the British Library, see it as a unique phenomenon. The truth of the matter is far more interesting.

The beginning of the flood tide of magical innovation that brought the Golden Dawn into being can be dated to 1854, when the French occultist Alphonse Constantwriting under his pen name liphas Lvipublished the first volume of Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie ( Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic ). Lvi, as he may as well be called here, was an extraordinary and too-often underrated thinker who studied for the priesthood in a series of Catholic seminaries, left before ordination, and was active in radical politics for several years before finding his lifes work as the first great modern writer on magic. At a time when popular opinion dismissed occultism as superstitious nonsense, Lvi was able to restate the basic principles of magic in a form that the reading public of the nineteenth century found understandable and appealing. In the process, he kickstarted a revival of magic that is still ongoing.

Lvis genius was that his theory of magic combined a first-rate knowledge of traditional occultism with an equally keen understanding of those intellectual currents of his time so that a contemporary audience could make sense of magic. He reworked the old philosophy of magic, which was heavily tinged with the scholasticism of the Middle Ages and opaque to most people by his time, in terms drawn from the cutting edge of nineteenth-century philosophy and science. The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, then hugely popular, wrote about the world as the product of will and representation; Lvi borrowed this by positing that magic is the product of will and imagination. Nineteenth-century physics accepted the idea of a subtle substance pervading the universe, providing the basis for light, heat, electricity, and magnetism; Lvi borrowed the idea, renamed it the Astral Light, and postulated that it was the medium that transmits magical influences from mind to mindor from mind to matter.

Another key to Lvis success was the way he redefined the image of the practitioner of magic. During the Renaissance, when magic had last been popular and respected in Western culture, magicians had envisioned their art as a way to the fulfillment of the highest reaches of human possibility. Since that time, reduced to a hole-and-corner existence as members of a despised subculture, magicians had done as socially marginal groups so often do, accepted the wider cultures negative opinion of them without ever quite noticing that this was what they were doing. Lvi restored magic to its old dignity, but in updated terms: in an age that was intoxicated with the dream of conquering nature, he offered the promise of nearly limitless power and wisdom to those who were willing to rise to the greater challenge of conquering themselves.

This act of redefinition relaunched occultism back into the popular culture of Lvis time, giving it a foothold in the collective imagination for the first time since the onset of the Scientific Revolution two centuries earlier. In the wake of Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie and a string of sequels from Lvis busy pen, an occult subculture emerged, first in France, then in other European countries and overseas as well. As the new subculture expanded, it found an unexpected audience among Freemasons.

Freemasonry itself was finishing up a century of extraordinary innovations when the nineteenth-century revival of magic began. When it originally went public in 1717 with the founding of the first Grand Lodge of England, Freemasonry had only two degrees of initiation, Entered Apprentice and Fellow Craft. A third, Master Mason, was added around 1720; the Royal Arch, the first of what came to be known as the higher degrees, appeared at some point before 1743, the date when it was first mentioned in Masonic records. Thereafter the floodgates opened, and literally thousands of new degrees came into being. Most of these lasted only a little while, but some of the best found their way into an assortment of rites, or systems of degrees, that took shape around the beginning of the nineteenth century. The York Rite of ten degrees and the Scottish Rite of thirty-three were the most successful of these rites, and both of them are still active today.