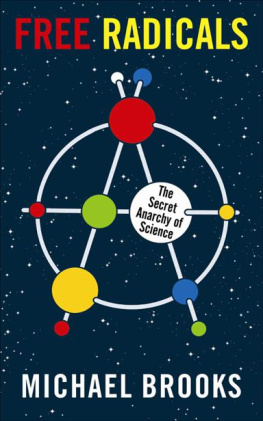

Free Radicals

MICHAEL BROOKS , who holds a PhD in quantum physics, is a consultant at New Scientist magazine and writes a weekly column for the New Statesman . His writing has appeared in the Guardian , the Independent , the Observer , Times Higher Education and many other newspapers and magazines. He has lectured at New York University, The American Museum of Natural History and Cambridge University. His first book, 13 Things That Dont Make Sense was translated into eight languages. www.michaelbrooks.org

Also by Michael Brooks

13 Things That Dont Make Sense

The Secret Anarchy of Science

MICHAEL BROOKS

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3A Exmouth House

Pine Street

London EC1R 0JH

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright Michael Brooks, 2011

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset in Minion by MacGuru Ltd

info@macguru.org.uk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Clays, Bungay, Suffolk

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84668 405 0

eISBN 978 1 84765 449 6

The paper this book is printed on is certified by the 1996 Forest

Stewardship Council A.C. (FSC). It is ancient-forest friendly. The printer

holds FSC chain of custody SGS-COC-2061

CONTENTS

That is the essence of science: ask an impertinent question, and you are on the way to a pertinent answer.

Jacob Bronowski

PROLOGUE

I t is 5.15 pm on 23 March 2003. In a brightly lit auditorium in Davis, California, Harvard cosmologist Lisa Randall is trying to give a talk about her research. The audience contains some of the greatest scientific minds on the planet, even some Nobel laureates, but no one is paying Randall any attention. Even she is having trouble concentrating. Her eyes flick repeatedly from her notes to the front row of the audience. There, on the far right of the auditorium, Stephen Hawking is being given his tea-time soup. Its quite a sight.

Earlier in the day Hawking gave a sparkling talk, crammed with witty asides and acerbic commentaries on the state of science. It was delivered via his speech synthesiser, with that hallmark monotony; Hawking is paralysed by motor neuron disease and simply cannot speak for himself. Eating is similarly problematic.

His nurses are trying their best to avoid a spectacle, but it is difficult. The spoon wont quite go into his mouth, and the soup dribbles down his chin. It is unquestionably distracting: not one of these fine minds has the capacity to ignore the goings-on in the front row and focus exclusively on Randalls talk. Discomfiting as this scenario is, there is an upside. Here, in this strange moment of their lofty, cerebral lives, it has become clear, just for a moment, that these scientists are very human beings.

The humanity of scientists and what that really means is what this book is about. For more than fifty years, scientists have been involved in a cover-up that is arguably one of the most successful of modern times. It has succeeded because even the scientists havent understood what has been going on.

After the Second World War, science was given a makeover. It was turned into a brand in the same way that Coca-Cola, Apple Computers, Disney and McDonalds are brands. The brand identity of science is reinforced with adjectives such as logical, responsible, trustworthy, predictable, dependable, gentlemanly, straight, boring, unexciting, objective, rational. Not in thrall to passions or emotion. A safe pair of hands. In summary: unhuman.

The creation and protection of this brand the perpetuating of the myth of the rational, logical scientist who follows a clearly understood Scientific Method has coloured everything in science. It affects the way it is done, the way we teach it, the way we fund it, its presentation in the media, the way its quality control structures in particular, peer review work (or dont work), the expectation we have of sciences impact on society, and the way the public engages with science (and scientists with the public) and regards scientists pronouncements as authoritative. We have been engaging with a caricature of science, not the real thing. But science is so vital to our future that it must now be set free from its branding. It is time to reveal science as the anarchic, creative, radical endeavour it has always been.

Sciences domination of todays world belies the fact that it is a relative newcomer as a profession perhaps one of the newest. , as Michael Schrage has put it: their wizardry could tip the balance of the superpowers in the twinkling of a quark.

, was the professionalisation and routinisation of science as a remunerated job. So, with the prospect of secure funding, steady jobs and even good pensions, scientists set about making themselves look worthy of the investment. The first task was to solve their image problem.

At the end of the Second World War, when this process began, scientists were mistrusted. Though their power was enticing to governments, it was also disturbing. , warned Winston Churchill, and what might now shower immeasurable material blessings upon mankind may even bring about its total destruction.

makes sciences dilemma plain:

It is arguable whether the human race have been gainers by the march of science beyond the steam engine. Electricity opens a field of infinite conveniences to ever greater numbers, but they may well have to pay dearly for them. But anyhow in my thought I stop short of the internal combustion engine which has made the world so much smaller. Still more must we fear the consequences of entrusting a human race so little different from their predecessors of the so-called barbarous ages such awful agencies as the atomic bomb. Give me the horse.

The fear of sciences power is almost palpable. Penicillin and radar had helped the Allies survive the conflict, but it was the scientists cataclysmic unleashing of atomic energy that won it. And it was the scientific mind that produced the rockets that had rained down on London, causing such devastation and misery. Tales about the inhumanity of science were leaking out too: reports of scientists conducting gruesome and inhuman experiments in the German concentration camps, and of Japanese medical research on prisoners of war..

The scientists first move was to dissipate the unease the public felt about sciences power and sense of responsibility; science would henceforth serve the people. Science projected itself as responsible and safe: a careful, measured discipline involving sensible, level-headed people not given to dangerous passions. and broadcaster Jacob Bronowski put it just a few years after Hiroshima, the scientist became the monk of our age, timid, thwarted, anxious to be asked to help.

It was a deliberate policy: whenever British scientists of the post-war era allowed television cameras into their laboratories, for example, the message was upbeat and optimistic, , rages a character in a 1960s drama, you kill half the world, and the other half cant live without you.

Next page