Contents

Guide

Contents

The Hubble Space Telescope, with its lack of background light or atmospheric interference, has allowed scientists to look deep into space from 1990, with a projected end of mission around 2030.

Introduction

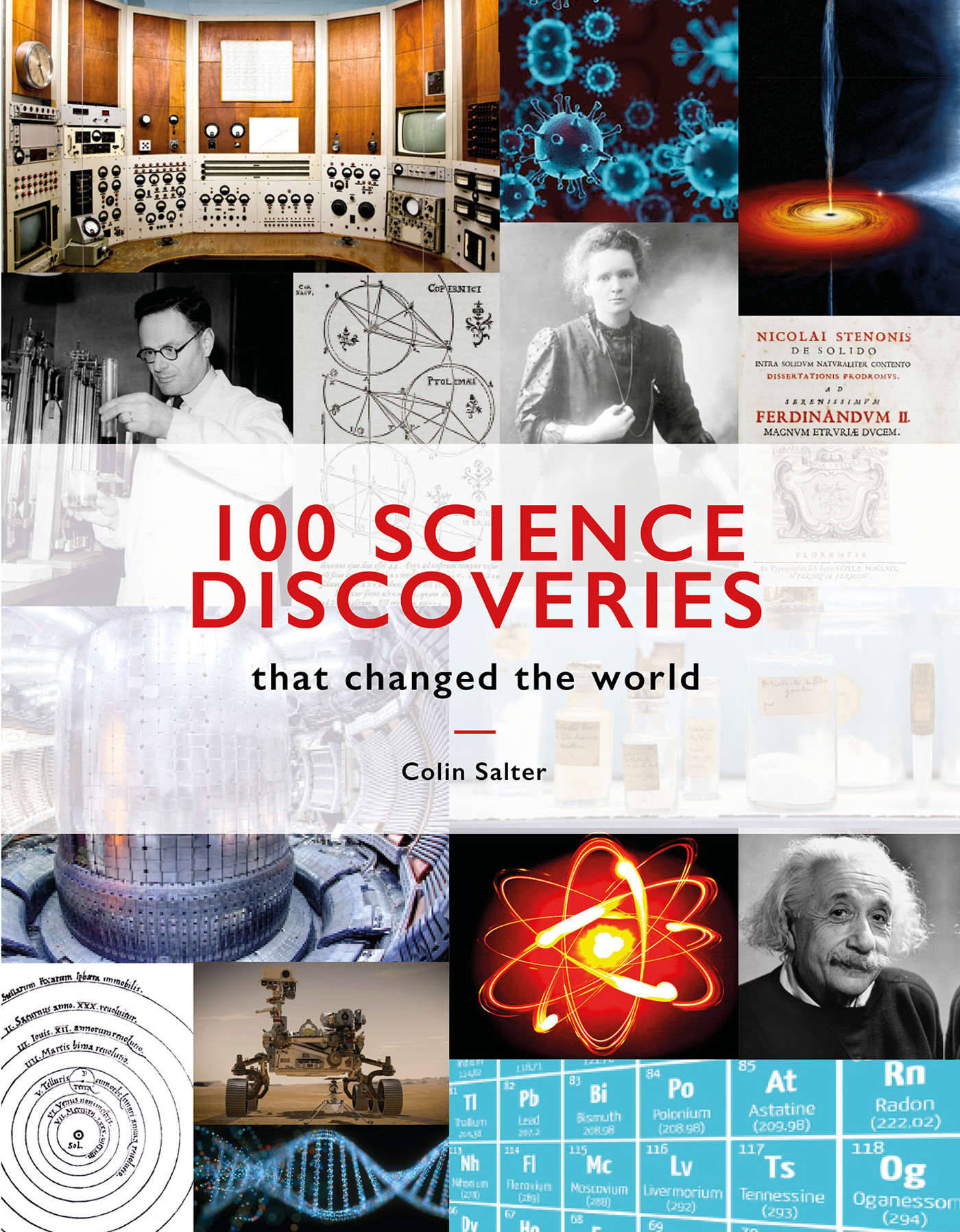

The history of science is measured in milestones of discovery. Each new milestone allows other scientists to further advance the sum of human knowledge. As Sir Isaac Newton said, If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.

A merican sci-fi author Frank Herbert noted that the beginning of knowledge is the discovery of something we do not understand. It is a human condition to make sense of our surroundings. Homo sapiens is an inquisitive species and it is a scientists profound curiosity that brings discoveries, pushing at the boundaries of the known world and bringing order to chaos.

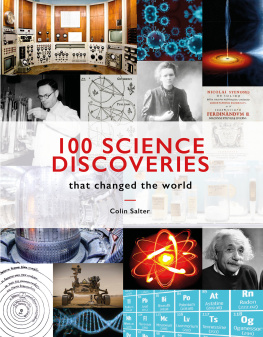

A distinction should be made early on between discovery and invention. There is a significant difference between discovering a rule or a law of pure science and the harnessing of that knowledge to transform the world. No better example of this can be found than Heinrich Hertz, who established the existence of radio waves, but could think of no real use for them. Invention is the employment of discoveries, and thats the subject for another book. This one hand-picks one hundred of the most significant discoveries in history, made by the sharpest, most curious minds in science.

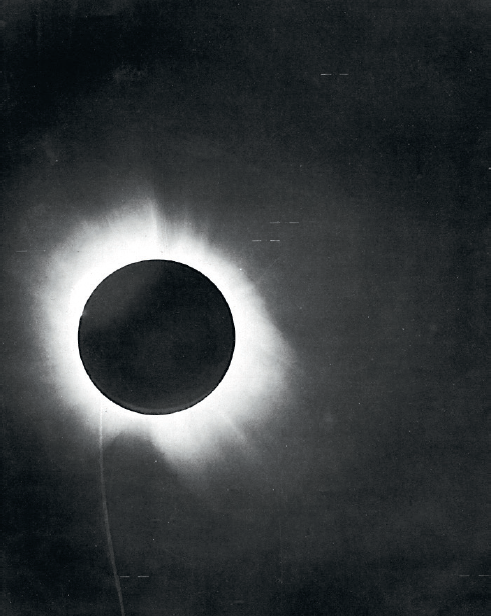

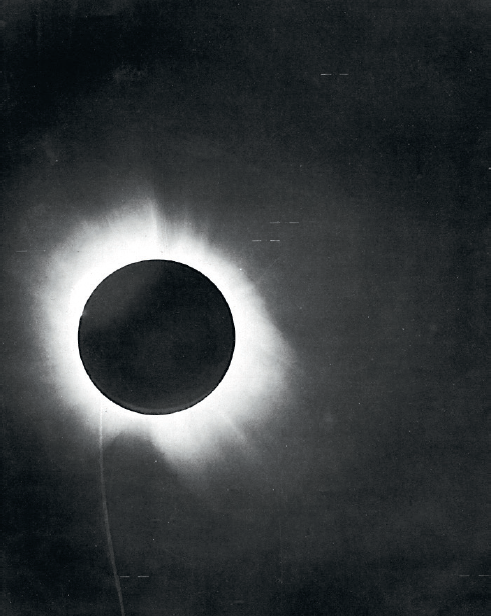

Arthur Eddingtons capture of images from the 1919 total eclipse advanced many areas of science.

History tends to remember discoverers rather than inventors. That is perhaps unfair to inventors; but if asked to name some famous scientists the average person would probably come up with those who made breakthroughs in knowledge: Marie Curie, who discovered radium; Isaac Newton and his Laws of Motion; Alexander Fleming who revealed the properties of penicillin; not forgetting Einstein, Galileo, Pasteur and the rest.

They are all here, starting with Euclid, whose codification of geometry was mans first attempt to quantify his environment the very word means land measurement. The urge to bring order out of chaos through measurement and classification is the beating heart of science. It might be a list of the elements, a knowledge of different blood groups, or the melting points of superconductors; but when someone wanted to know why some materials burn, why the body rejects some blood transfusions, or what happens when you freeze certain gases, they were taking the first steps in discovering something.

HAPPY ACCIDENTS

Not all great scientists find what they are looking for; but the best are able to identify an anomaly and pursue it. Alexander Fleming, for example, had been studying bacteria before his annual holiday. He cleared his Petri dishes to one side before he left so that his colleague had space to work. On his return two weeks later he found that fungus, borne on the air from the room below his laboratory, had contaminated one of the dishes and killed off the bacteria which he had been growing.

The fungus was penicillin, the first great antibiotic, and Fleming was always modest about his fame as its discoverer the Fleming effect as he called it. Its true that the whole thing was an accident caused by an open window and someone elses dirty room. But more than one scientist has addressed the question of accidental discovery. A discovery, said Albert Szent-Gyorgyi, the Hungarian biochemist who first isolated Vitamin C, is an accident meeting a prepared mind.

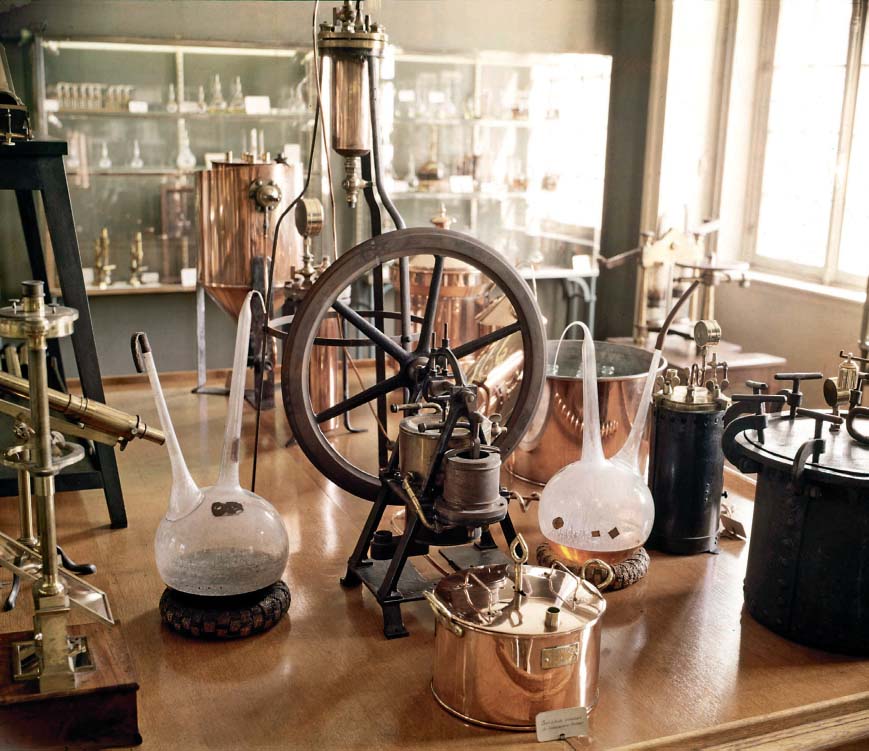

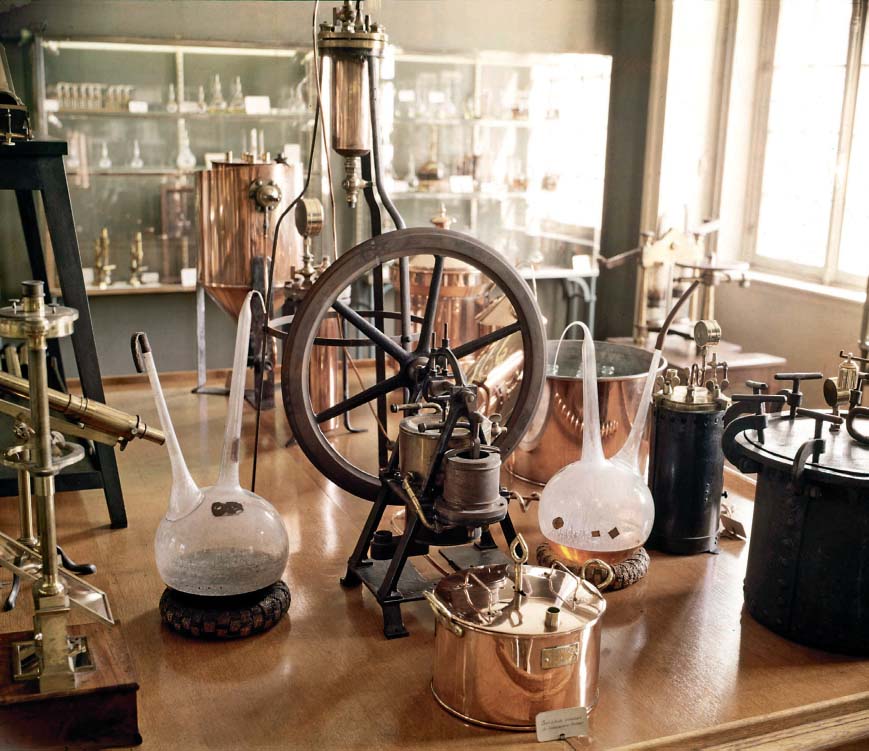

Some of Louis Pasteurs original equipment on display at the Muse Pasteur, part of the Pasteur Institute in Paris.

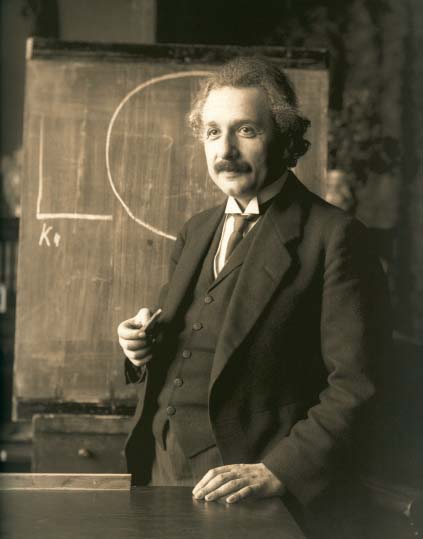

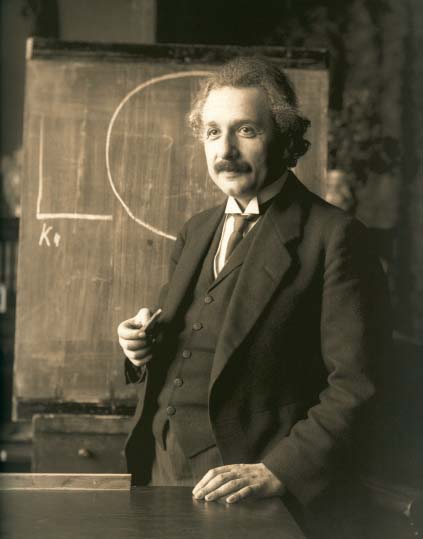

His name has become synonymous with genius, Albert Einstein in 1921. However, it is comforting to note he didnt get everything right, and disputed the Big Bang theory.

Accidents never happen accidently, said Andre Geim of Manchester University, who along with Konstantin Novoselov discovered the properties of wonder material graphene in 2004. Good scientists create the environment for as many as possible of those accidents to happen. In other words, a discoverer has to be in the right place with the right frame of mind to learn from the right mistakes.

STANDING ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS

Hundreds of millions of lives have now been saved with penicillin and other antibiotics, thanks to Flemings accident. But that would not have been possible without Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, a seventeenth-century Dutch draper, whose fascination with microscopes led him to discover bacteria. And as genetics pioneer Sir Henry Harris said, Without Fleming, no Chain [who discovered the molecular properties of penicillin]; without Chain, no Florey [who conducted the first treatment with the antibiotic]; without Florey, no Heatley [who discovered a way of mass-producing it]; without Heatley, no penicillin.

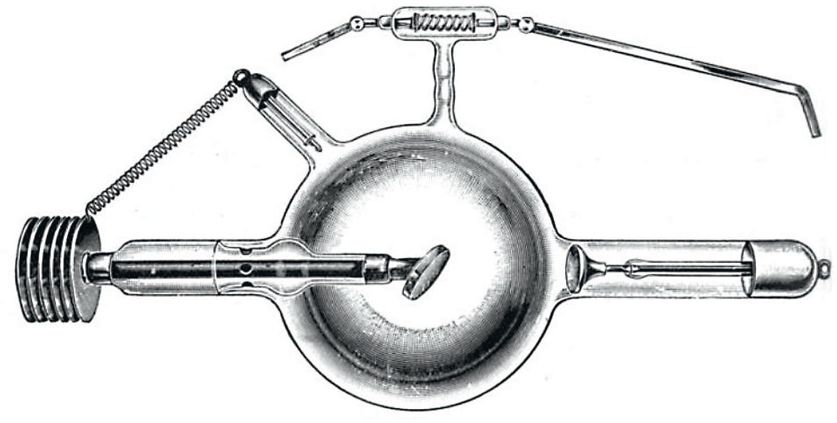

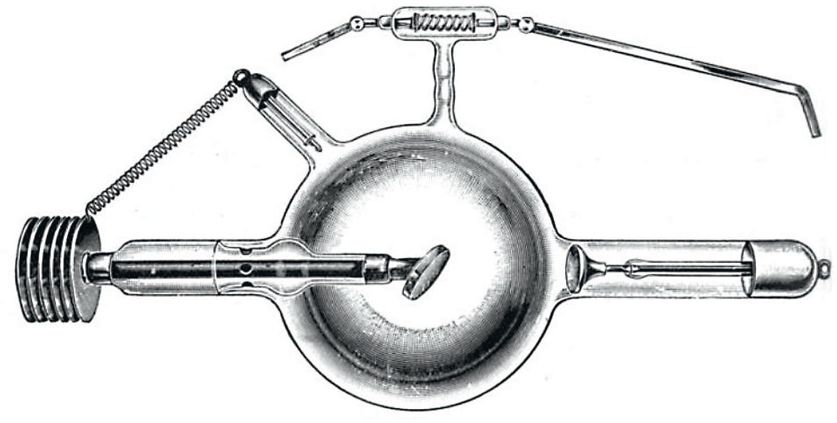

Wilhelm Rntgen was experimenting with a Crookes (electrical discharge) Tube when he stumbled across the phenomenon of X-rays.

Scientists depend on their predecessors discoveries to make discoveries of their own. Another science fiction author, Isaac Asimov, observed that, there is not a discovery in science, however revolutionary, however sparkling with insight, that does not arise out of what went before. Scientists have always depended on the groundwork laid down by their forebears. Even that most baffling of physical arenas, quantum theory, was the result of a set of scientific laws discovered over two millennia which worked for earthbound events but could not fully explain all cosmological phenomena.

In an increasingly complex scientific world, scientists also depend more and more on their contemporaries, either working together or corroborating each others discoveries. Gone are the days when enthusiastic amateurs such as van Leeuwenhoek, with a microscope in the back of the shop, could make paradigm-shifting observations. Science began to receive professional status toward the end of the eighteenth century William Herschel, who discovered the planet Uranus, received a stipend when he was appointed Astronomer Royal in the court of British king George III; and his sister Caroline Herschel, who discovered many comets, was the first professional female scientist in 1787, when she became his paid assistant.