ANCIENT PHILOSOPHY

FROM 600 BCE TO 500 CE

The History of Philosophy

ANCIENT

PHILOSOPHY

FROM 600 BCE TO 500 CE

EDITED BY BRIAN DUIGNAN, SENIOR EDITOR,

PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION

Published in 2011 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.)

in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright 2011 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2011 Rosen Educational Services, LLC.

All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor

J.E. Luebering: Senior Manager

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

Brian Duignan: Senior Editor, Philosophy and Religion

Rosen Educational Services

Alexandra Hanson-Harding: Editor

Shalini Saxena: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Matthew Cauli: Designer, Cover Design

Introduction by Brian Duignan

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ancient philosophy: from 600 BCE to 500 CE / edited by Brian Duignan.

p. cm.(The history of philosophy)

In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61530-243-7 (eBook)

1. Philosophy, Ancient. I. Duignan, Brian.

B108.A53 2010

180dc22

2009054263

Manufactured in the United States of America

On the cover: Plato was one of the greatest philosophers ever to have lived. Fuelled by a desire to fully comprehend the nature of reality, Plato, along with his teacher, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, largely pioneered the development of Western philosophical thought. Today, everything from metaphysics to ethics to political philosophy owes much the work of Plato and his contemporaries. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

On : Thales, shown here, is the first known Greek philosopher and one of the Seven Wise Men of antiquity. His belief that water formed the basis of the universe marked a significant deviation from the more widespread myth-based explanations of the time. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

CONTENTS

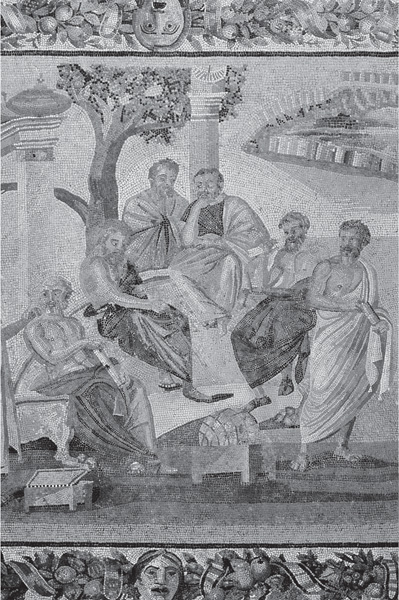

INTRODUCTION

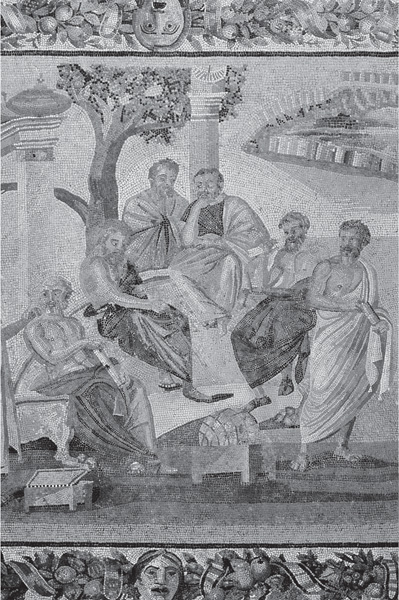

Plato founded the Academy outside Athens in the 380s BCE where followers of his philosophy were taught in subjects like mathematics, dialectics, and natural science. He is shown here speaking with his students. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples, Italy/The Bridgeman Art Library/Getty Images

M ore than 2,500 years ago, in the early 6th century BCE, a few inhabitants of the Greek city of Miletus (on the western coast of what is now Turkey) began to think about the world in a new way. Like many people before them, they wondered how the world was created, what it is made of, and why it changes (or seems to change) as it does. Unlike their predecessors, however, the Milesians attempted to answer these questions in natural rather than religious terms. They appealed to what they thought were causes and principles in the world itself, rather than to the acts of gods or other divine beings. Importantly, they believed that the proper way to understand the world is through reason and observation. Because they speculated about profoundly important questions in a rational and systematic way, the Milesians are recognized as the first Western philosophers.

During the 6th century BCE the Greeks also became the first people to practice science and mathematics in the modern sense of those terms. By the middle of the 3rd century BCE the Greeks had produced a finished system of geometrical reasoning (that of Euclid) that would not be significantly amended for more than 2,000 years; by the end of the 4th century they had created nearly all of the basic problems, concepts, methods, and vocabulary of subsequent Western philosophy. Until the late 3rd century CE, other philosophers from the Greek world produced sophisticated and original theories in ethics, epistemology (the study of knowledge), metaphysics (the study of the ultimate nature of reality), and logic. Starting in the first century CE, Jewish and, later, Christian thinkers adopted aspects of the metaphysical system of the Greek philosopher Plato (428348 BCE) to help them defend and clarify the doctrines of their faiths.

What is called the ancient period in the history of Western philosophy is traditionally divided into four periods, or phases: the Pre-Socratic, extending from the early 6th century to about the mid 4th century BCE; the Classical, to the end of the 2nd century BCE; the Hellenistic, up to the late 1st century BCE; and the Roman, or Imperial, to the early 6th century CE, ending with the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

The term Pre-Socratic refers to philosophers who were not influenced by Socrates (470399 BCE), in most cases because they lived before him. Unfortunately, no work of any Pre-Socratic philosopher has survived; what is known of their teachings consists of various (mostly critical) references in works by later philosophers, especially Plato and Aristotle.

The Milesians, as we have seen, were the first to speculate rationally about the origin and nature of the world; for this reason they and others like them are called cosmologists. The first of the Milesians, Thales, held that everything is water, by which he meant that the different substances of which the world appears to be composed are ultimately derived from water. The two other members of the Milesian school, Anaximander (610546 BCE) and Anaximines (flourished 545 BCE), along with later cosmologists from other Greek cities, proposed various numbers and varieties of primordial substances and various processes by which they were transformed into one another. Anaximander was also noteworthy for advancing a theory of the evolution of living things: humans and all other animals, he said, evolved from fishes. Heraclitus of Ephesus asserted that the basic substance is fire and the basic process strife; the apparent unity and permanence of things in the world are the result of the constant conflict of opposites. Thus everything is in a state of flux, or constant change, a view he famously expressed by saying, You cannot step into the same river twice. Parmenides, who was born in the Greek city of Elea in southern Italy in 515 BCE, argued to the contrary that nothing changes, and the apparent multiplicity of things in the world is an illusion: all is one. His disciple Zeno of Elea (495430 BCE) is famous for inventing a series of quite sophisticated paradoxes (apparently valid arguments that lead to absurd conclusions) designed to show that all multiplicity and change are impossible; some of these arguments were not definitively refuted until the 20th century.

Next page