Dominican Series

The Dominican Series is a joint project by Australian Dominican women and men and offers contributions on topics of Dominican interest and various aspects of church, theology and religion in the world.

Series Editors: Mark OBrien OP and Gabrielle Kelly OP

1. English for Theology: A Resource for Teachers and Students, Gabrielle Kelly OP, 2004.

2. Towards the Intelligent Use of Liberty: Dominican Approaches in Education, edited by Gabrielle Kelly OP and Kevin Saunders OP, 2007.

3. Preaching Justice: Dominican Contributions to Social Ethics in the Twentieth Century, edited by Francesco Campagnoni OP and Helen Alford OP, 2008.

4. Dont Put Out the Burning Bush: Worship and Preaching in a Complex World, edited by Vivian Boland OP, 2008.

5. Bible Dictionary: Selected Biblical and Theological Words, Gabrielle Kelly OP in collaboration with Joy Sandefur, 2008

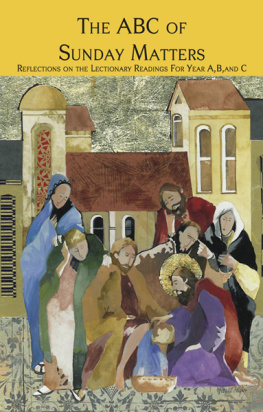

6. Sunday Matters: Reflections on the Lectionary Readings for Year A, Mark A OBrien, 2010.

7. Sunday Matters: Reflections on the Lectionary Readings for Year B, Mark A OBrien, 2011.

8. Sunday Matters: Reflections on the Lectionary Readings for Year C, Mark A OBrien, 2012.

9. Scanning the Signs of the Times, edited by Thomas F OMeara OP and Paul Philibert OP, 2013.

10. From North to South: Southern Scholars Engage with Edward Schillebeeckx, edited by Helen Bergin OP, 2013.

Disclaimer:

Views expressed in publications within the Dominican Series do not necessarily reflect those of the respective Congregations of the Sisters or the Province of the Friars.

Text copyright 2013 remains with the author.

All rights reserved. Except for any fair dealing permitted under the Copyright Act, no part

of this book may be reproduced by any means without prior permission. Inquiries should

be made to the publisher.

Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

| Author: | OBrien, Mark A, 1945- author. |

| Title: | The ABC of Sunday matters : re$ections on the lectionary |

| readings / Mark OBrien. |

| ISBN: | 9781922239440 (paperback) |

| EPUB ISBN: | 9781922239464 |

| Series: | Dominican series. |

| Notes: | Includes bibliographical references. |

| Subjects: | Bible--Homiletical use. |

| Lectionary preaching--Catholic Church. |

| Dewey Number: | 269.2 |

Cover design by Astrid Sengkey

Original artwork by Yvonne Ashby

Original lino cut by Yvonne Ashby

An imprint of the ATF Ltd

PO Box 504

Hindmarsh, SA 5007

ABN 90 116 359 963

www.atfpress.com

Table of Contents

Introduction

Sunday matters or should matter to Christians. It is the Lords day and so the most important day of the week, a time for us to acknowledge God as the source, centre and goal of our lives. Because Sunday is important there are important matters to consider on this day, such as making time for prayer, worship and reflection on the Word of God. But there are also many other matters that now vie for our time and attention on Sunday: sport, shopping, TV, travel, etc. Deciding what to do on Sunday and other major days of the Christian calendar has become something of a challenge for contemporary Christians, some would say even a crisis.

But a crisis or a challenge can provide an opportunity to rethink and refocus, and here the Bible serves as an invaluable aid. In my judgement the Bible itself is an invitation or challenge to think. It does not impose its views because that would be most ungodlikeaccording to the biblical understanding of God. Much of life is about making decisions and the Biblechallenges us to decide where our priorities lie and provides invaluable guidelines. The reflections offered in this book seek to draw out this role of the Bible in a hopefully clear and concise manner. They originally appeared in separate volumes for each year of the Churchs liturgical cycle (years A, B, C) but have now been combined for convenience in this single volume.

The reflections originally appeared in the Australasian Catholic Record over a 3-year period as Reflections on the Readings of Sundays and Feasts (2007-9).to cover all the Sundays of the three-year cycle and make the material more accessible to the general reader as well as the preacher. Those who do not have a lectionary or follow its cycle of readings can easily correlate biblical text and reflection by consulting the index at the end of the book.

It may be of some help to readers to provide an introductory outline of how I read biblical texts as well as an overview of the Biblea broad context within which to reflect on the particular readings selected for each Sunday. The bibliography at the end of the volume offers opportunities to check the outline and overview offered here and to correct and improve on them where necessary.

All human beings, even inspired biblical authors, communicate something (the content or message) by assembling selected parts of their language in particular literary forms (the ways of communicating). In the Old Testament the preferred literary forms are narrative (story, report, genealogy, etc), poetry (psalms, proverbs, prophecies) and law (commands, prohibitions, instructions); in the New Testament they are narrative (in the Gospels and Acts of the Apostles) and letters (of Paul and others). A literary form provides a creative opportunity but also imposes limitations. For example, a story usually involves a plot (such as overcoming an evil) with a limited cast of characters. A storyteller has to develop the plot towards some form of resolution and this means being selective, otherwise the story could become too unwieldy and lose something of its impact.

What authors include or leave out of their compositions is also influenced by their historical and social context. The context in which ancient authors operated had no equivalent to the modern novel with its intricate plots, large cast of characters and elaborate detailbut even these have their limitations. Most biblical stories or parables, songs or prophecies, are fairly short and it is likely many biblical texts are written distillations of longer oral performances. Writing in ancient times was time consuming and expensive: it is unlikely a scribe could write down all of an actual oral performance. But they were very adept at recording the key elements of a story or song that would serve as a guide for further performances. Stories, poems, Gospels and letters were written for public proclamation, elaboration and comment. Thankfully, this is still the case for our Sunday liturgies in which a short selection of texts from the Bible is proclaimed for us to listen to, to preach on and to discuss. People in ancient times had excellent memories but they also had a smaller corpus of material to memorise. We now have to rely on computers and memory sticks or flash drives to store an ever increasing corpus of texts that is beyond our capacity to memorise.

I have been trained in modern western critical methods of reading the Bible but also respect the traditional ways of reading that have been used in the Church and Synagogue since their inception. Both have to operate with the fundamental premise that one can only understand what a text is communicating by paying close attention to the way it is communicating (the literary form employed). We all do this instinctively in our own cultural and historical context and with literature with which we are familiar: we distinguish headline from commentary, editorial from a letter to the editor, advertisement from operating manual. Sporting enthusiasts know that a headline announcing cats maul dogs is about a football match not a brawl between pets. When we come to the literature of another culture we need to be aware that two different contexts are coming in contactour own and that of the other culture.

Next page