All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of Random House, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

S PIEGEL & G RAU and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

PREFACE

When the people of my small mountain town got their first dose of electrical lighting in late 1924, they were appalled by the brightness and crudity of the resulting illumination, wrote local historian Alf Evers. As Christmas approached, a protest was staged on the village green denouncing the evils of modern light.

Old people swore that reading or living by so fierce a light was impossible. Besides which, it was a matter of pride: Every flaw in their household furnishings was shown up. That much light invited comparisons. It threw everything in sharp relief. It was an advertisement for the new, the rich, and the beautifula verdict against the old, the ordinary, and the poor.

A few days later the naysayers got their way. The power failed, and Christmas on the village green was celebrated with nothing but candlelight to pierce the solstice, the darkest time of the year. Ive searched the annals of the town to see if there were any further protests before it went fully electric a year or so later, but I havent found any. Here as elsewhere in early twentieth-century America, the reluctance to embrace brighter lights was a brief and halfhearted affair.

People sensed there was something wrong with the new technology. They just couldnt say what it was. All but the most cantankerous felt foolish to oppose a product as clean and cheap as electrical light. It was so cheerful and convenient and downright wholesome that any argument against it seemed wrongheaded, maybe even evil. After all, what good Christian would argue in favor of the dark?

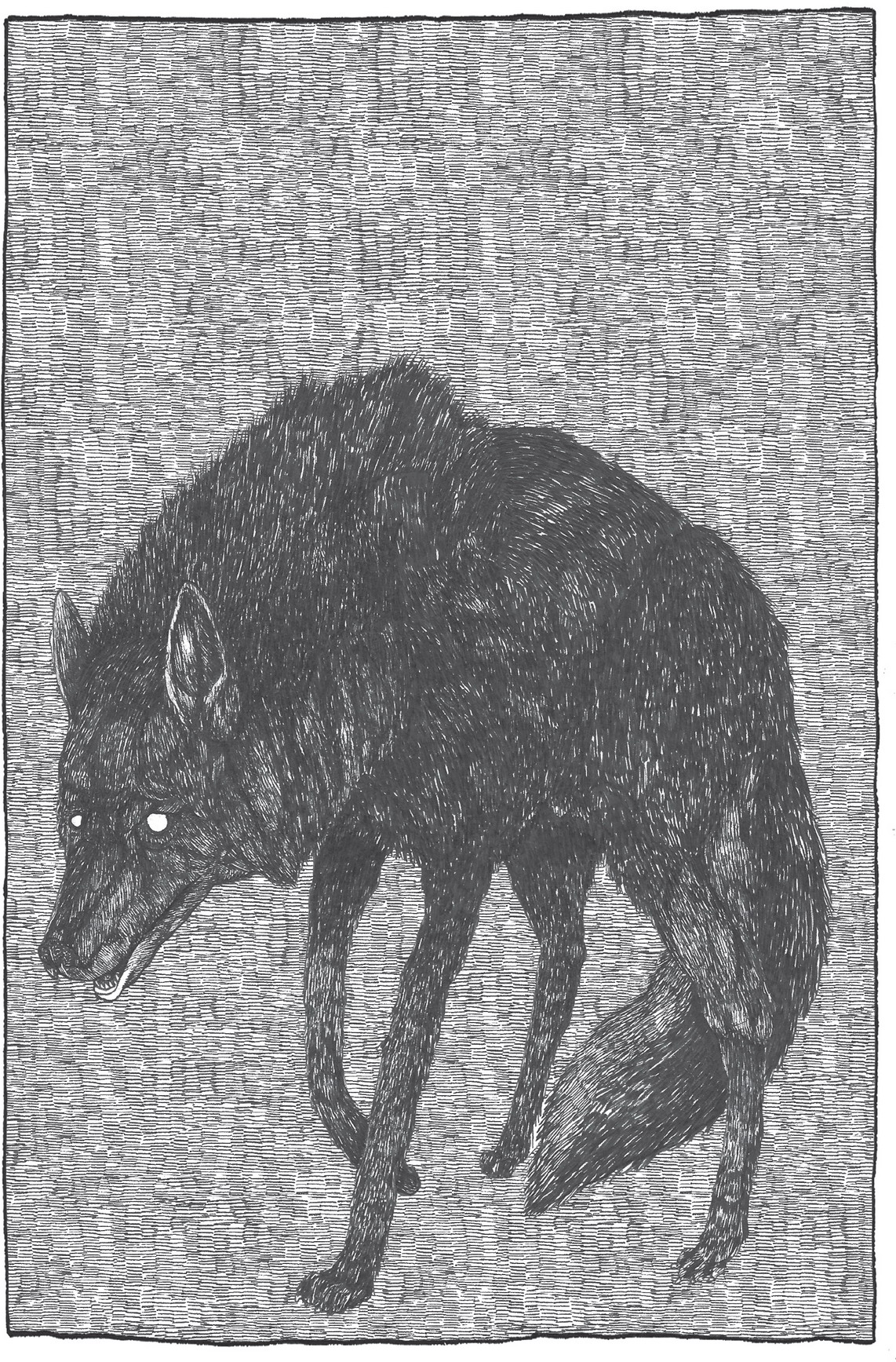

There was no stopping the century of progress for which Edisons invention was literally the guiding light. Who could have known it was the worst thing that could happen to the planet? We dont know the value of darkness until we have destroyed it. We dont know what a soul is worth until it is gone.

I am not afraid of the dark.

My wife insists that this is the reason people listen when I speak on spiritual matters. I spent years studying Zen Buddhism. After that, I immersed myself in spiritual practices from all over the world. But none of that made me wiser or more enlightened than anyone else. It isnt the reason people listen.

From childhood on I have woken up in the middle of the night and sought out the darkness. Not only am I not afraid of it, I love it more than anything. Thats what people are drawn to without knowing it. Its important to them for reasons they find difficult to explain. Its as if Ive reminded them of something they once knew, but can now no longer recall.

As a young child in Alabama, I began slipping out into the night whenever I could. We lived in a small town in a house only one block from the golf course. I loved the big heady silence of the starry fairways and the pockets of darkness in the trees between the links that almost seemed absolute.

Once, when I was caught coming home, my mother demanded to know what I had been doing, and I pretended I had been sleepwalking. I wasnt a noticeably eccentric child, but I knew there was something strange about my nighttime wanderings. My mother believed the lie, or probably she just chose to believe. After all, I was wearing shoes. But it was just as well. What drove me on these midnight rambles? I would have been at a loss to explain, even if she had asked.

By the time I was a teenager, I was often walking five miles or more in the middle of the night. I strolled through backyards and graveyards, found my way through fences and fields. I felt profoundly at home in the dark. We moved so often when I was a child that it was hard for me to find the kind of comfortable footing with friends and teachers that most children take for granted. So my inner home, my dream home, became the darkness itself.

I went to a college situated atop a large plateau and surrounded by thousands of acres of wilderness. I hiked at night, discovering caves and cliffs. I climbed water towers and visited abandoned barns. I felt protected, not just by the bounds of the university, but by nature itself. Out in the fields under the stars alone, I had no one to please but myself.

I never carried a flashlight. The nights were rarely so dark, even in the country, that you couldnt feel your way along a path or road. I once hiked up a mountain in complete darkness on a summer night with a thick canopy of leaves blocking out the sky. There was no moon. I listened to the sounds my feet made on the pebbles of the path. If I stepped on leaves, I corrected myself and found the trail again. After two hours I arrived at the summit and finally saw the stars.

It was a wonder my health didnt suffer from lack of sleep, but it never did. Even then I was on the verge of knowing something about darkness and the human body, and about consciousness and our relationship to the divine and how they all depended on each other. But I had no framework then for that understanding. It was entirely experiential. Even later, in the midst of my Zen training, I would not connect my nighttime rambles through the monastery graveyard with the concerted training I was undergoing in the meditation hall. It never occurred to me that out in the inky blackness of the mountains I was on the trail of a deeper, more ancient practice all but forgotten to the world.

Many of us wake up in the middle of the night and cant get back to sleep.

We worry about our money and our health. About our kids and our marriages. About how little sleep we are getting and how tired we will be the following day. We often turn on the lights to get through those sleepless hours. Or we surf the Internet or watch TV. My father read scores of tedious, half-forgotten Victorian novels to span the midnight hours. Sometimes we take a pill our doctor has prescribed to manage insomnia, rather than risk waking up in the dark.