Copyright 2014 Ronald R. Bernier. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical publications or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher. Write: Permissions, Wipf and Stock Publishers, W. th Ave., Suite , Eugene, OR 97401 .

W. th Ave., Suite

Bernier, Ronald R.

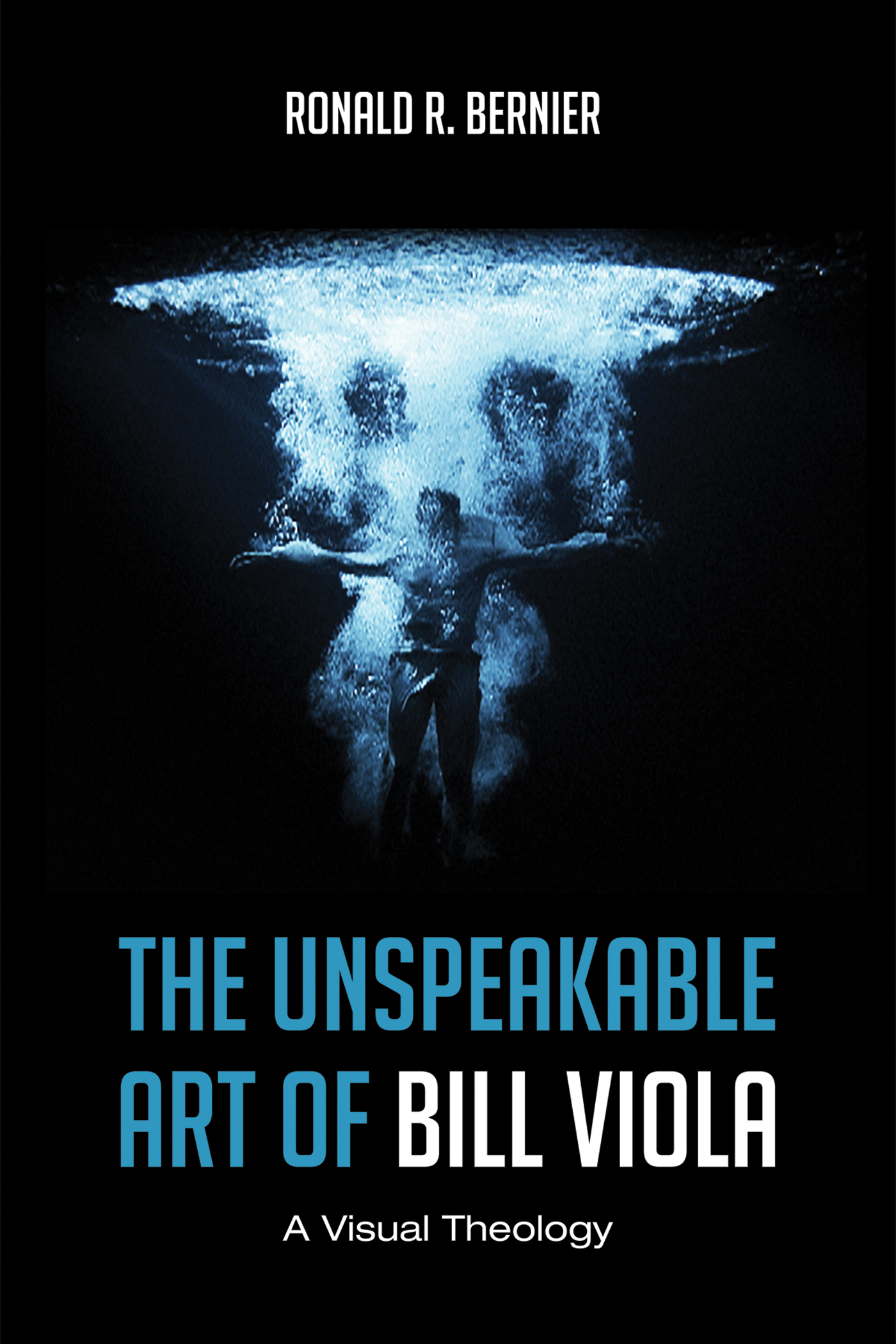

The unspeakable art of Bill Viola : a visual theology / Ronald R. Bernier.

xiv + p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references.

. Viola, Bill , 1951. 2 . Art, Modernth century.. Spiritual lifeChristianity. I. Title.

Manufactured in the U.S.A.

For Michael I. Podro, CBE, FBA

Acknowledgments

T his project is the result of countless iterations and reconsiderations over the years, and many individuals have been tremendously helpful and generous with their time, guidance and editorial acumen along the way. Its first outing was as a graduate thesis in the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at the University of Scranton, in Scranton, PA, under the able direction of Dr. Maria Poggi Johnson. Her support, encouragement and insight shepherded the project from a vague spark of an idea to its first stage of completion. Also influential along that route were Drs. Charles R. Pinches and Will T. Cohen, also at the University of Scranton. From there various chapters and portions of chapters were presented, in various stages of (in)completion, at several professional academic meetings in recent years, including the Association of Art Historians annual conference in Manchester, UK in 2009 , the Association of Scholars of Christianity in the History of Art in Paris in 2010 , the Museum of Biblical Art in New York in 2011 , and the American Academy of Religion in San Francisco in 2011 . At each step, thoughtful questions were raised and astute suggestions offered that helped to make the argument more cogent and focused. Support for travel to many of these professional venues was made possible by the generosity of the Provosts and the Presidents Offices of Wentworth Institute of Technology in Boston, MA, where as faculty Ive also received supportive and perceptive feedback from students and colleagues.

For the editorial and production assistance in the final sprint to publication I wish to thank Christian Amondson and the wonderfuland patientstaff of Wipf and Stock Publishers.

And finally, I owe a tremendous debt of gratitude for the kindness and warm spirit of Bill Viola, Kira Perov, and their assistant, Christen Sperry-Garcia of Bill Viola Studio LLC, who gave generously of their time and insight as this project reached its final (for now) form.

Introduction

Towards a Visual Theology

For in hope we were saved. Now hope that is seen is not hope. For who hopes for what is seen? But if we hope for what we do not see, we wait for it with patience.

Romans :

T he estrangement of art from religion is one of the many unhappy legacies of Modernism. There was a time, however, when the aesthetic and the theological were of a piece. This study of selected works by American video artist Bill Viola

Long estranged from symbol and sacrament, artists seem to have turned once again to a vision rooted in the soul, where soul may be understood, in a Hegelian sense, as that which transcends individuality and bonds us with other people and communitiesart as a way of re-humanizing us, summoning us to a rekindled humanity and a social instinct of empathy with others, what Viola himself has described as an awareness that may counter the anti-human tendencies in todays world. In an era marked culturally by world-weary cynicism and solipsistic and self-conscious irony, a new paradigm may be emerging within an artistic practice that has grown increasingly uncomfortable with its inherited condition of unbelief and has re-committed itself to a project of restoring theology to aesthetics.

Quite to the contrary, however, contemporary theorist Thierry de Duve has argued for a continued faith in the Enlightenment project that others have generally agreed has failed us; de Duves hope is that artists not engage lingering interests in spirituality, maintaining that the best modern art has endeavored to redefine the essentially religious terms of humanism on belief-less bases.

In the introduction to his popular 2004 study, On the Strange Place of Religion in Contemporary Art , art historian and theorist James Elkins succinctly describes my own sense of professional unease in pursuing this topic: For people in my profession of art history, Elkins confesses, the very fact that I have written this book may be enough to cast me into a dubious category of fallen and marginal historians who somehow dont get modernism or postmodernism.

The present contribution to the discussion aims to challenge that assumed secularism of institutional art historywhat Sally M. Promey describes as the secularlization theory of modernity which contends that modernism necessarily leads to religions decline, and the secular and the religious will not coexist in the modern world, My study aims to resist the pervasive skepticism when it comes to religion as a topic of discussion in the academy, to move beyond our contemporary and unhelpful model of the secular left (militant atheism) and evangelical right (dogmatic theism), and to come to terms with faith as an irrecusable part of the fabric of the social. More specifically, my purpose is to speculate on the place of the sacred in contemporary visual culture, and, in doing so, to consider the key features of any contemporary theological aestheticsthat it be revelatory and transformative. Bill Violas art, I shall argue, provokes the possibility of just such theological reflection.

Fortunately, a much welcome new publication, ReVisioning: Critical Methods of Seeing Christianity in the History of Art , edited by historians James Romaine and Linda Stratford, brings together more than a dozen essays by both emerging and established scholars, which collectively seek to expand the discourse on Christianity in the history of art, in part by challenging the equation of modernism with secularism as a methodological approach to the writing of art history. Romaine writes in the books Introduction:

The prevailing narrative of art history is one that charts a movement from the sacred to the secular, progressing out of past historical periods in which works of art were produced to reveal, embrace, and glorify the divine and toward a modern conception of art as materialist and a more recent emphasis on social context. In fact, for many art historians this secularization of art is not only a narrative within the history of art; it has been the narrative of art history as an academic field. Some interpretations of twentieth and twentieth-first century art not only insist on equating modernism with secularism but also describe the erasure of all mention of spiritual presence from the scholarly discourse as a triumph for the field of art history.

The present study seeks to contest that narrative and to contribute to an emerging field that still lacks the methodological framework by which to honestly and meaningfully address arts engagement with theology, or at the very least with a religious awareness that, as Dyrness put it, slips away in the very effort to grasp it. The theological framework I will engage here begins with the ancient tradition of apophatic , or negative, theologyGod talk (theology) that seeks to describe God only in terms of what may not be said about God, what God is not . This is the topic of my second chapter. In the words of th-century mystic John the Scot Eriugena: We do not know what God is. God Himself does not know what He is because He is not anything. Literally God is not, because He transcends being.

![Viola Spolin - Improvisation for the Theater: A Handbook of Teaching and Directing Techniques [1963 ed.]](/uploads/posts/book/406435/thumbs/viola-spolin-improvisation-for-the-theater-a.jpg)