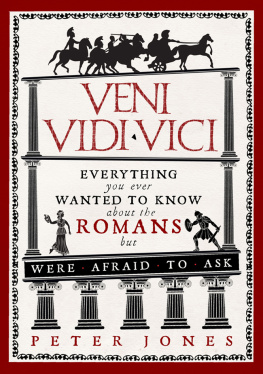

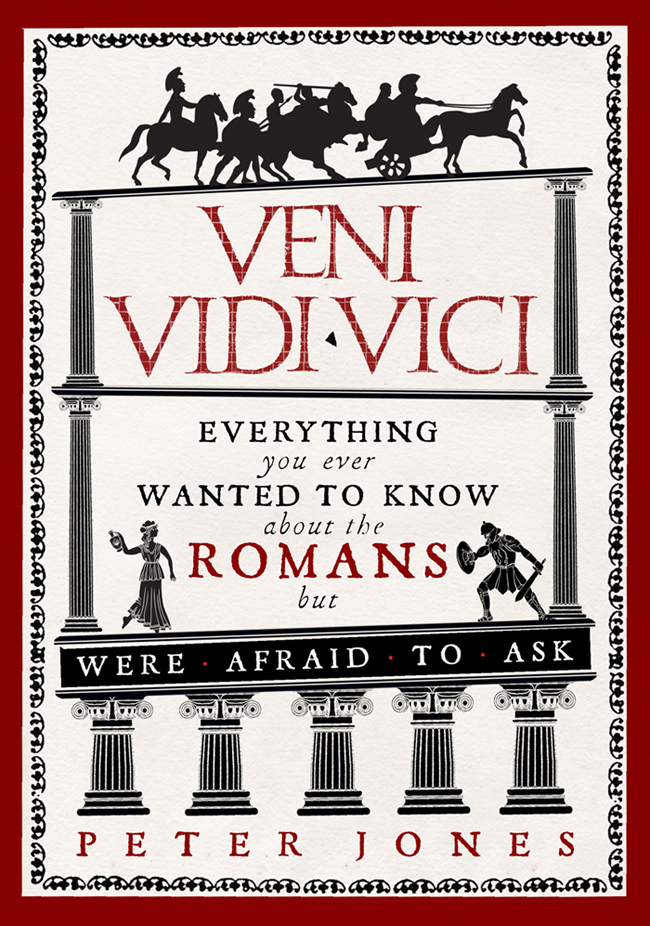

VENI

VIDI  VICI

VICI

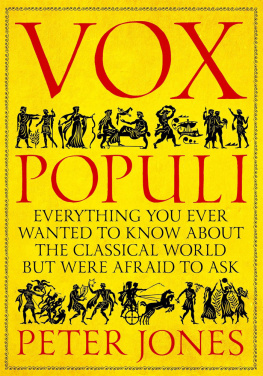

Also by Peter Jones

Vote for Caesar

Classics in Translation

Published in Great Britain in 2013 by Atlantic Books,

an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright Peter Jones, 2013

The moral right of Peter Jones to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-84887-903-4

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-78239-020-6

Designed by Carrdesignstudio.com

Printed in Great Britain.

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

CONTENTS

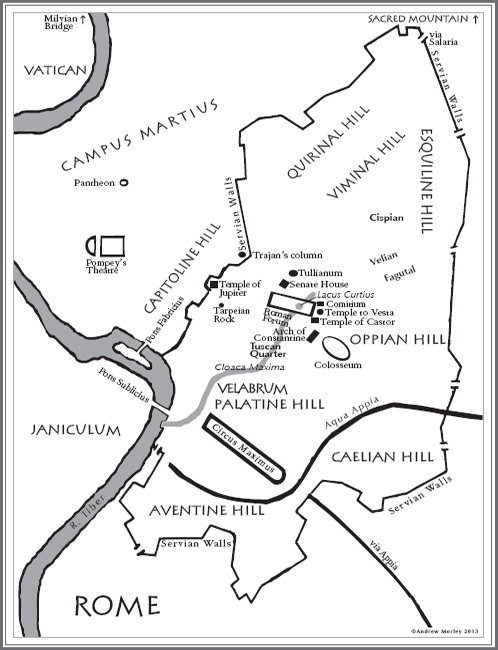

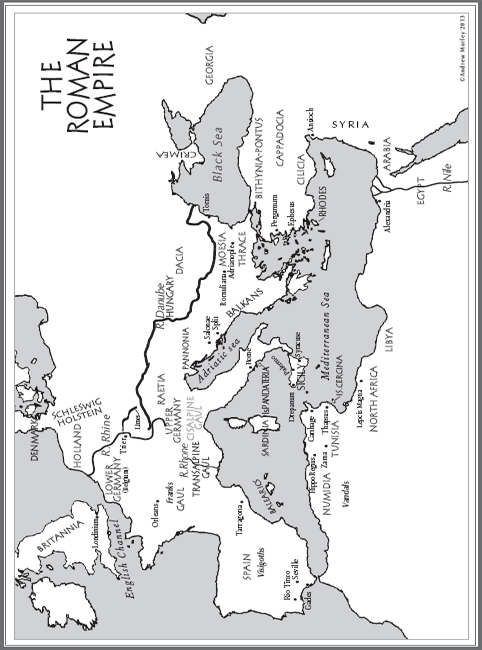

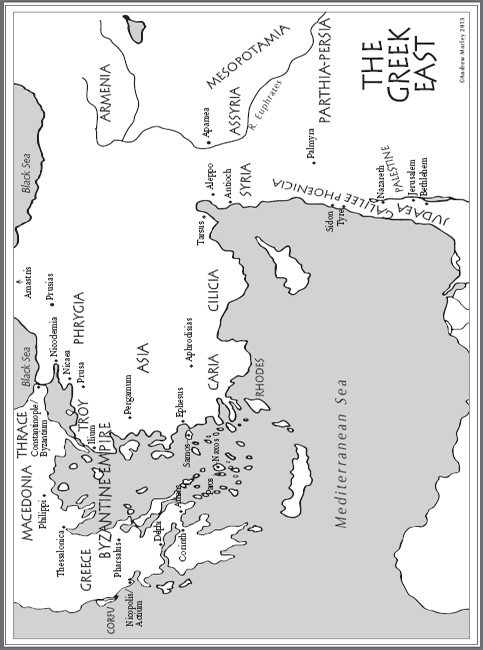

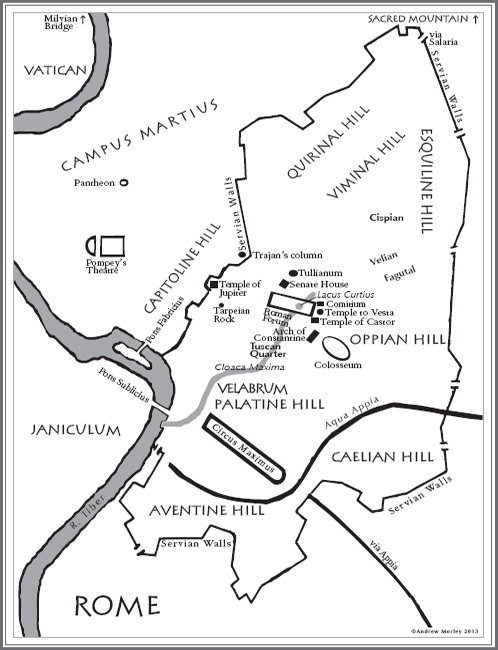

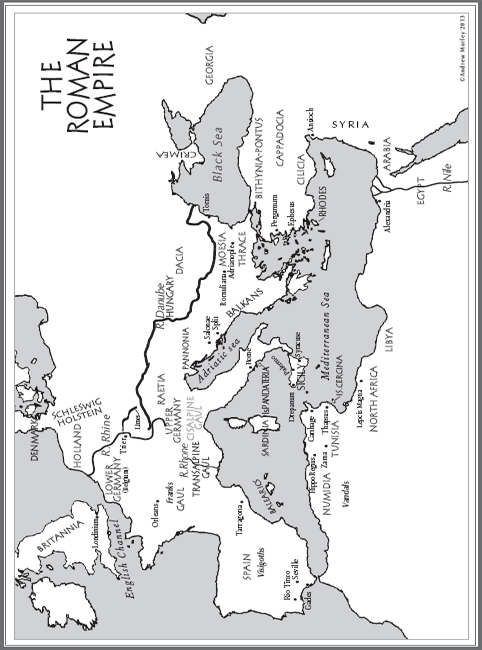

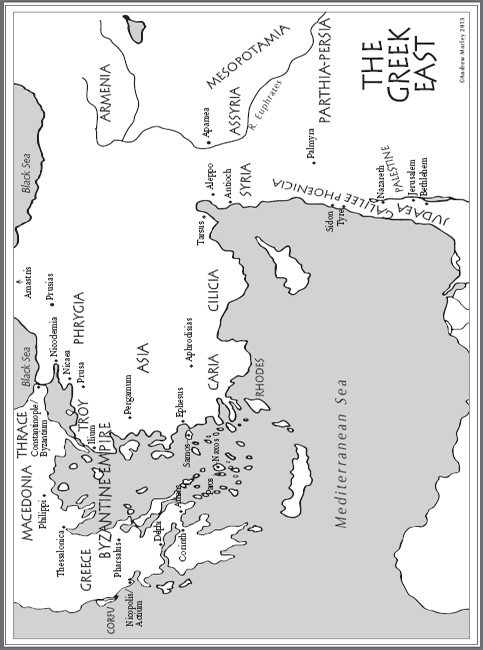

MAPS

INTRODUCTION

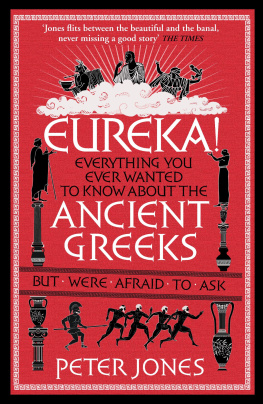

T his book is the 1,200-year story of Rome from its earliest foundation in 753 BC to the end of its empire in the West in AD 476. It is a story everyone should know because, like that of Ancient Greece, it has shaped our world and penetrated our imagination: from its language, literature, politics, architecture, philosophy, empire and legal system to the individuals that created its story; from Romulus and Remus to Scipio and Hannibal; from Lucretia to Lesbia and Boudicca; from Pompey and Julius Caesar to Cicero and Augustus; from Pontius Pilate to Constantine; from Nero and Hadrian to Marcus Aurelius and St Augustine; from Catullus to Virgil and Tacitus to St Jerome; from the unknown inhabitant of Pompeii who scratched on a wall: I came here, had a shag, then went home the last of the great romantics to the equally unknown person who invented the book or produced concrete that would set under water.

Each chapter begins with a broad summary of the period it covers. The rest of the chapter is taken up with a sequence of 100500-word nuggets. These reflect the same chronological sequence as the summary, and expand on the topics that the summary raises (this leads occasionally to small repetitions) or explore new, related ones. The nuggets aim to be self-contained, as far as possible; but occasionally there will be a sequence of nuggets on one topic (e.g., gladiators) where a degree of continuity will be observed. The overall purpose is to present sharp, focussed and stimulating information within the developing story of a crucial period of European history.

This is, unashamedly, a book for the general reader. It is designed for someone who wants to see something of the big picture, but also to be alerted to some of the detail that underpins it. Intense argument lies behind many of the assertions made here. Those who wish to find out more about these may care to consult the reading list at the back. A few passages have been adapted from my Vote for Caesar (Orion, 2008) and Classics in Translation (Bloomsbury, 1998).

The sources I have quoted are adapted from translations that are out of copyright, many of them from the first editions of the Loeb Classical Library. The poems have been adapted where necessary. I am most grateful to His Honour Colin Kolbert for permission to quote from his superb Justinian: The Digest of Roman Law (Allen Lane, 1979). I am also very grateful to Dr Federico Santangelo at Newcastle University for help with some difficult questions of chronology; and, as ever, to Andrew Morley for the maps.

Peter Jones

Newcastle upon Tyne, November 2012

www.friends-classics.demon.co.uk

NOTE ON

FINANCIAL VALUES

I t is impossible to fix the relative value of Roman money to today's prices. Here are some prices expressed in sesterces (ss), around AD 1: a 1lb (1.5 kg) loaf of bread, a plate, a lamp and a measure of wine cost less than 0.25 s; an unskilled labourer could earn three ss a day; it cost 500 ss a year to feed a peasant family; a soldier's pay was 900 ss a year; an unskilled slave cost 2,000 ss; you needed property worth 400,000 ss to qualify as among Rome's richest, and one million ss to become a senator; Pliny the Younger over a lifetime gave away 5 million ss in benefactions.

PAGANISM

W hen I talk of pagans I do not mean Wicker men and such like. I mean those who engaged in the civic cults and rituals of the pre-Christian Roman world (see p. 359). Paganism in this sense, organized by state-sanctioned colleges of priests, died out in the fifth century AD. That said, Roman literary and political culture in the broadest sense the sense of the tradition behind the grandeur that was Rome continued to shape Christian thought for centuries to come.

I

TIMELINE

1150 BC | Mythical Trojan War between Greeks and Trojans |

1000 BC | Rome a small collection of hilltop huts in Latium |

753 BC | Traditional Roman date for King Romulus founding of Rome |

First record of early form of Latin |

700 BC | Homer's account of Trojan War (Iliad and Odyssey) |

400 BC | Greeks reckon Trojan Aeneas founded Rome after Trojan War |

LOST IN THE MYTHS OF TIME

From Aeneas to Romulus, Remus and Rome

R omans came up with two stories about how they were founded. One (bewilderingly, we might think) was pure Greek. It was drawn from perhaps the most famous episode in what Greeks thought of as their very early, heroic history: the Trojan War, the story of the Greek siege of Troy (in western Turkey) to win back Helen. Ancients thought of it as occurring about 1200 BC.

This formed the subject of the West's first literature: the epic Iliad, composed by the Greek poet Homer c. 700 BC at a time when many Greeks were emigrating to Sicily and southern Italy. In Homer's story a minor Trojan hero, Aeneas, was fated to survive the war and later establish a dynasty that would rule over a resurrected Troy. But, Homer went on, Troy was burned to the ground by the Greeks and abandoned, and the surviving Trojans fled the country. So where did they and Aeneas go? How could Aeneas resurrect Troy? From as early as the sixth century BC Greeks began to wonder about this too; and some said that Aeneas passed through Italy with other Greek and Trojan heroes of that war. In the late fifth century BC the Greek historian Hellanicus named Aeneas as the founder of Rome whether prompted by Romans, we do not know.

VICI

VICI