EIHEI DGEN

MYSTICAL REALIST

Wisdom Publications

199 Elm Street

Somerville, MA 02144 USA

www.wisdompubs.org

2004 Hee-Jin Kim

Foreword 2004 Taigen Dan Leighton

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or later developed, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

Kim, Hee-Jin.

Eihei Dgen : mystical realist / Hee-Jin Kim ; foreword by Taigen

Dan Leighton.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-86171-376-1

1. Dgen, 1200-1253. 2. StshDoctrines. I. Leighton, Taigen

Daniel. II. Title.

BQ9449.D657 K56 2004

294.3'927'092dc22

2003021350

14 13 12 11 10

5 4 3 2

Cover design by Rick Snizik. Interior design by Gopa & Ted2, Inc. Set in Diacritical Garamond 10.75/13.5. Cover photo by Gregory Palmer / kinworks.net

Wisdom Publications books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Printed in the United States of America.

This book was produced with environmental mindfulness. We have elected to print this title on 30% PCW recycled paper. As a result, we have saved the following resources: 14 trees, 4 million BTUs of energy, 1,287 lbs. of greenhouse gases, 6,198 gallons of water, and 376 lbs. of solid waste. For more information, please visit our website, www.wisdompubs.org. This paper is also FSC certified. For more information, please visit www.fscus.org.

To those friends

who helped me understand Dgen

FOREWORD TO THE WISDOM EDITION

BY TAIGEN DAN LEIGHTON

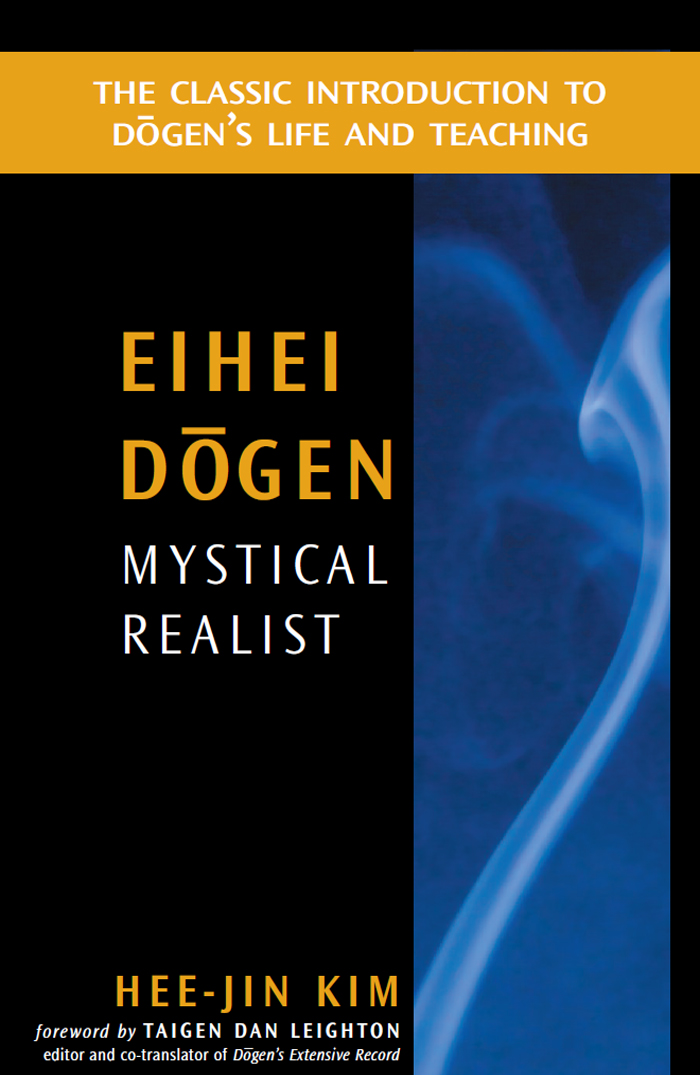

H EE-JIN KIMS LANDMARK BOOK Eihei Dgen: Mystical Realist (formerly titled Dgen Kigen: Mystical Realist) is a valuable, highly insightful commentary on the work of the thirteenth-century founder of the St branch of Japanese Zen. This book is an excellent comprehensive introduction to Dgens massive corpus of intricate writings as well as to his elegantly simple yet profound practice. Kim clarifies that Dgens philosophy was at the service of his spiritual guidance of his students, and reveals the way Dgen incorporated study and philosophy into his religious practice.

Since this book was first published in 1975, and even more since the revised edition in 1987, a large volume of reliable English-language translations and commentaries on Dgen have been published. And a widening circle of varied meditation communities dedicated to the practice espoused by Dgen has developed in the West, with practitioners eager to study and absorb his teachings.

I have been privileged to contribute to the new body of Dgen translations and scholarship. Other translators such as Shohaku Okumura, Kazuaki Tanahashi, Thomas Cleary, and Francis Cook have all made Dgens writings much more available to English readers, and now we even have a serviceable translation of the entirety of Dgens masterwork Shbgenz, thanks to Gudo Nishijima and Chodo Cross. These new translations supplement the excellent early translations of Norman Waddell and Masao Abe that predate Kims book, but have only recently become more accessible in book form. Furthermore, excellent commentaries on specific areas of Dgens life and teaching by such fine scholars as Steven Heine, Carl Bielefeldt, William Bodiford, Griffith Foulk, and James Kodera, to name a few, have created a thriving field of Dgen studies in English. Nevertheless, after all this good work and a few years into the twenty-first century, this book by Hee-Jin Kim from the early years of English Dgen studies easily still stands as the best overall general introduction to Dgens teaching, both for students of Buddhist teachings and for Zen practitioners.

Even beyond the realm of Dgen studies, this book remains a valuable contribution to all of modern Zen commentary, with Kims accessible presentation of thorough scholarship that does not reduce itself to dry intellectual analysis of doctrines or historical argumentation. Kim provides a subtle and clear discussion of Dgens work as a practical religious thinker and guide, showing that Dgen was not merely a promulgator of philosophy, and never considered his work in such terms.

Kim unerringly zeroes in on key principles in Dgens teaching. The organization of this book is extraordinarily astute. After first providing background on Dgens biography and historical context, Kim discusses with subtlety Dgens zazen (seated meditation) as a mode of activity and expression. Kim then focuses on the centrality of the teaching of Buddha-nature to Dgens teaching and practice. Finally, Kim elaborates the importance of monastic life to Dgens teaching and training of his disciples.

In explicating the purpose of zazen for Dgen, Kim enumerates the meaning and function of key terms that provide the texture of Dgens teaching and practice: the samdhi of self-fulfilling activity (jijuy-zammai), the oneness of practice-enlightenment (shush-itt), casting off of body and mind (shinjin-datsuraku), non-thinking (hishiry), total exertion (gjin), and abiding in ones Dharma-position (j-hi).

With all the confusion about meditation in Zen, historically and today, we must be grateful at the acuity of the introduction to Dgens zazen that Kim has provided. Unlike other forms of Buddhism and even other Zen lineages, Dgen emphatically does not see his meditation as a method aimed at achieving some future awakening or enlightenment. Zazen is not waiting for enlightenment. There is no enlightenment if it is not actualized in the present practice. And there is no true practice that is not an expression of underlying enlightenment and the mind of the Way. Certainly many of the kans on which Dgen frequently and extensively comments in his writings culminate in opening experiences for students in encounter with teachers. And the actuality of the zazen practice still carried on by followers of Dgen may often include glimpses, sometimes deeply profound, of the awareness of awakening. But such experiences are just the crest of the waves of everyday practice, and attachment to or grasping for these experiences are a harmful Zen sickness. The Buddhas awakening was just the beginning of Buddhism, not its end. Dgen frequently emphasizes sustaining a practice of ongoing awakening, which he describes as Buddha going beyond Buddha.

Although current meditators may appreciate the therapeutic and stress-reducing side-effects of zazen, for Dgen, as Kim clarifies, zazen is primarily a creative mode of expression instead of a means to some personal benefit. In one of the hgo (Dharma words) in Dgens Extensive Record (Eihei Kroku), Dgen speaks of the oneness not only of practice-enlightenment, but the deep oneness of practice-enlightenment-expression. Just as zazen is not waiting for enlightenment, expounding the Dharmathe expression of awarenessdoes not wait only until enlightenments aftermath. There is no practice-enlightenment that is not expressed; there is no practice-expression of Buddha-dharma that is not informed with enlightenment; and there is no enlightenment-expression unless it is practiced. We might say that Dgens zazen is a performance art in which its upright posture and every gesture expresses ones present enlightenment-practice. Kim explicates how such creative practice-expression is not a matter of some refined understanding, but of deep trust in the activity of Buddha-nature: Zazen-only cannot be fully understood apart from consideration of faith.

Next page