DIGNITY

DIGNITY

Its History and Meaning

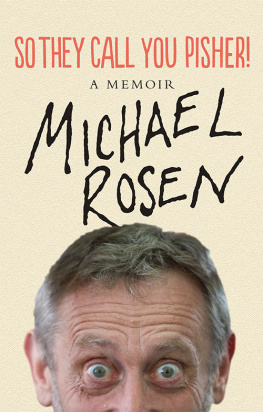

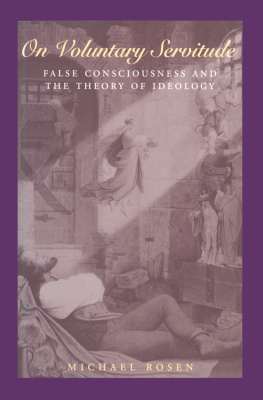

MICHAEL ROSEN

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England

2012

Copyright 2012 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Jacket design: Tim Jones

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Rosen, Michael, 1952

Dignity : its history and meaning / Michael Rosen.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 978-0-674-06443-0 (alk. paper)

1. Dignity. 2. Respect for persons. I. Title.

BJ1533.R42R67 2012

179.7dc23 2011032502

For Nancy Rosenblum

With affection, gratitude, and respect

CONTENTS

So tell me, my friend Christopher McCrudden, the distinguished human rights lawyer, said one day over coffee, what do philosophers have to say about dignity? I had read the novels of C. P. Snow and Michael Innes, and I always imagined that the air of Oxford Senior Common Rooms would be crackling with interdisciplinary exchanges. But, alas, if that kind of thing was going on, it had not been coming my way. So here was my chance! I must admit, though, that our conversation did not get off to the best start: Er, not very much that I know aboutKant perhaps? I replied.

Fortunately, Christopher proved a persistent (as well as tolerant) questioner, and the results of my further thinking (including many more conversations with him) are now in your hands. But before I thank those who helped to shape and correct my ideas, let me say something about the way that this book is presented.

It is often said that philosophy these days is not accessible to the general reader. This is obviously a matter for regret. If it is important that an educated person should have some understanding of the scientific knowledge on which our civilization relies (I have no doubt that it is), how much more so that she should have a conceptual framework within which to place that knowledge and some reflectively articulated principles by which to guide her action? In ethics and political life, issues of philosophical principle press on us whether we like it or not. When it is a question of deciding what action is right or whether to support a political proposal or arrangement, we must all decide for ourselveseven if, in the end, we decide to follow the direction of some authority (the case for doing which, by the way, is much less straightforward than for following the experts in a technical matter). So there is certainly a good reason for philosophy to try to reach an audience beyond its professional boundaries.

But that does not mean that it is possible. Perhaps the gap between philosophy and the general reader is inevitable. We dont imagine that someone could understand genetics or astrophysics without specialist trainingwhy should philosophy be different? It may be that this gap is the price we have to pay for progress.

Writing philosophy accessibly is certainly not easy. It is not that philosophy is intrinsically more difficult than other academic disciplines (they are all quite difficult enough, thank you!) but that philosophy is peculiarly resistant to one kind of popularization. As the many brilliant writers on science now active show, it is possible to present the results of scientific research (and even mathematics) in ways that dont require the reader to be able to follow the technical details that underlie them or to check for herself how those results were achieved. But to describe philosophys most advanced positions (even assuming that we agree what they are) in this way without also giving an account of the reasons for adopting them would be a complete waste of time. Philosophical arguments (good ones, at any rate!) make it possible for us to support rationally convictions that we have formed outside of philosophy or to challenge our complacency about things that we otherwise take for granted. They are the essential part of the subjectphilosophy without its arguments is like football without a ball.

We cannot usefully present philosophy without actually doing it, thenand yet to do philosophy presupposes a great deal. Philosophy is a holistic discipline. All of its theories and problems relate, in the end, to all the rest. So to address one problem we must haveif not resolved all of the others, at least be prepared to put them on hold for the time being. Not least, we (that is, author and reader) must have some shared understanding of what constitutes a good philosophical argument, and this (as philosophers know well, although non-philosophers are often surprised, and sometimes even outraged, to learn) is itself a matter of acute controversy. For a rough analogy, compare the philosopher with a chess player. If her argument were to be conclusive, the philosopher would have to be able, when she makes a move (that is, puts forward an argument or advocates a position), to meet all the counter-moves that might be made, and all the counter-moves to her own counter-movesin fact, to address the whole exponentially expanding tree-structure of possibilities that lies beneath that single move. But not just thathere is where chess and philosophy differshe must be prepared to justify why the game should be played according to just these rules and not other ones. So the ideal of completeness in philosophical argument is, in practice, wholly chimerical and the philosopher faces a repeated series of uncomfortable choices about what to take for granted and what to put on the table for debate at any stage. On the one hand, there must be shared assumptions between an author and her readers for argument to get going at all; on the other, challenging assumptions is precisely what philosophy (at least, philosophy at its best) is all about.

In consequence, the idea of proof in the strict sense has very little place in philosophy. Philosophical positions can rarely be demonstrated, because the alternatives to them are rarely wholly refutedgaps can almost always be plugged, even if the intellectual price of doing so may seem to reasonably open-minded people absurdly high. But this does not mean that philosophy is not a matter of rational argument. John Stuart Mill makes exactly this point in Utilitarianism. Although, he admits, questions of ultimate ends (and, hence, the justification of utilitarianism) are not amenable to proof, There is a larger meaning of the word proof, in which this question is as amenable to it as any other of the disputed questions of philosophy. The subject is within the cognisance of the rational faculty; and neither does that faculty deal with it solely in the way of intuition. Considerations may be presented capable of determining the intellect either to give or withhold its assent to the doctrine; and this is equivalent to proof. To put it more bluntly, just because we cant reach a mathematical ideal of proof, we shouldnt throw up our hands and conclude that philosophy is no more than personal preference. We can give reasons for and against positions, reasons that carry weight even if theyre not conclusive.

These, then, are some reasons of principle why philosophy is so hard to practice in an accessible way. They also, incidentally, help to explain its tendency to fracture into schools and traditions that talk past one another. The different traditions disagree not just about foreground substance, but also (what is more difficult to deal with) about the background assumptions that must be presupposed to get philosophical discourse going.

Yet there are also some bad reasons why philosophy today is inaccessible, most of them to do with over-professionalization (I am thinking here of the English-speaking world). My guess is that the dominance of the sciences in the academy, with their emphasis on peer review, has a good deal to do with it. Of course, there is a strong justification for papers in scientific journals being impersonally written and subjected to the disciplines of critical peer reviewnothing is more important in experimental science than establishing solid, repeatable resultsbut the idea of extending this to philosophy is questionable. Admittedly, accountability brings benefits in philosophy as well. (I wonder how far the pretentious, uncritical style of much contemporary Continental philosophy is a result of the lack of such discipline.) But something is lost too. If, for the reasons outlined above, the idea of completeness in philosophical arguments is unattainable, the attempt to be rigorous can lead to a defensive tendency to reduce ambitions and to protect some tiny piece of ground against the possible objections of those closest to oneself in background and outlook (ones natural peer reviewers). What is lost is not just accessibility but also the willingness to call into question basic assumptions (ones own and others), which is precisely what, for many of us, the point of doing philosophy was in the first place. Much contemporary philosophy takes place in an atmosphere of what can only be called (however historically unfair that label might be) scholasticism.