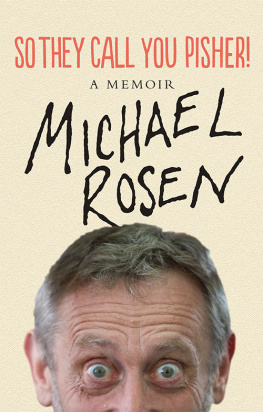

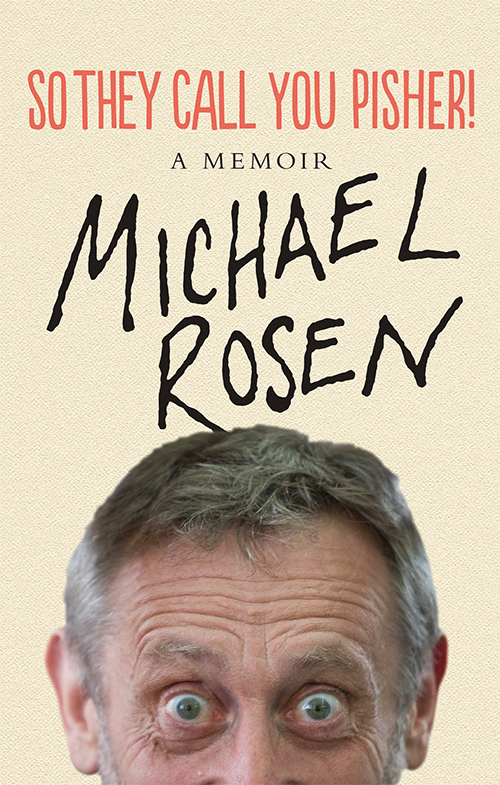

Names: Rosen, Michael Wayne, 1946 author.

Title: So they call you pisher! : a memoir / Michael Rosen.

Description: Brooklyn, NY : Verso Books, 2017. | Includes bibliographical

references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017010491 | ISBN 9781786633965 (alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Rosen, Michael. | Jewish men United States Biography.

Remembering Harold and Connie, and for Brian.

For Emma and our children, Elsie and Emile.

For Joe, Eddie, Isaac, Naomi and Laura.

A bout a year before I was born, my brother died; he was not yet two. I dont know the exact dates of his birth or the death. They were never marked or mentioned in our house or anywhere else. There was no memorial for him. There were no framed photos of him in our house. He was invisible. My arrival into the world must have been a mixture of delight and dread. Delight that I had come along to fill up the gap left by the one before. Dread that I could go too.

Its possible that I would never have found out about it, if it was not for the moment when I was ten, and my brother Brian and I were sitting on the floor of our front room, going through boxes of old photographs. I picked up one of my mother with a baby on her knee. I held it up.

Is that me or Brian? I said.

Our father, who we always called Harold rather than Dad, took it off me, looked at it closely and said, That isnt either of you. Thats Alan. He died. He coughed to death in your mothers arms. It was during the war. They didnt have the medicines. He was a lovely boy.

Brian and I sat right where we were, not knowing what to say. Mum looked so happy in the photo. For a moment I felt ashamed I had made this discovery. Maybe it would have been better if I hadnt found it.

I must have been the replacement child. Perhaps I was also a cough waiting to happen. Every snuffle, every slight rasp of a breath must have given them reason to worry. Ill never know if either or both of them voiced such thoughts because, as I say, my father only ever once told the story of the brother who died. My mother never told it, never mentioned it, never said the boys name, never let on that she knew that our father had talked about it to us.

T he first sounds I heard in the world were in a nursing home called The Firs in Harrow, halfway between Harrow-on-the-Hill station and Harrow School. The road, Roxborough Park, ran up a hill to the school, disappearing into a dark, green alleyway of old trees. The houses on both sides spoke of double-fronted, Edwardian wealth, some showing their middle-class past through their stuck-on black beams. Mock-Tudor was something my father would spit out on walks down the roads of Pinner, three miles away, where we lived. He had another phrase that topped mock-Tudor: phony barony. He would look over the hedges along roads around Pinner and say with venom in his voice, Look at that phony barony.

Brian, four years old by then, can remember coming to see me at The Firs. Mum held me up in the window while he and Harold waved from down below. I can imagine them walking in and Harold saying to her, Blimey, Con, I didnt ever think wed bring a kid into the world in a phony barony place like this.

Quite why phony barony was such a problem has only seeped into me slowly as an adult, from when I got to know more about where my parents, Harold and Connie, grew up. The places of their childhood and mine are as different as the middle of Paris and the Lake District. There had been no mock-Tudor where they were brought up, though the streets where they grew up arent any more real or authentic than the ones in Pinner. I think it was something he needed to say in order to show us that he wasnt attached to Pinner and Harrow: in his mind it wasnt only phony barony, it was full of phony barons.

Harold and Connie came from a place of myth: the East End. In reality, their East End was one small part of the eastern end of London, stretching from the River Thames in the south up to Bethnal Green in the north, with an eastern boundary at Bow and a western boundary at the City.

They talked of this area, or gestured towards it again and again and again. And yet, I was never taken on a trip to the streets of their childhoods. It never became a real place. By that time, Mums parents, who we visited, had moved northwards, a mile up the road in Hackney. In contrast, Harolds mother had moved eastwards by a few miles to live with her daughter Sylvias family in Barkingside. This put them near to where Sylvias husband Joe worked, at Fords.

While I was growing up, Harold and Mum decided not to bother with the scores of relatives that they each had. Aunts and uncles and cousins were mentioned particularly on Harolds side people called Lally and Milly and Rae and Leslie Sunshine and Hilda and Bernie and Murray and Sam and dozens more but we never saw them. Harold even did an imitation of his grandmother calling out all their names as she tried to remember which one she really wanted to come and help her: Rosie, Addy, Milly, Lally, Rae ! But it was as if they had been lost or locked away, living in places that would take days or weeks to reach.

It was only as an adult that I looked at the streets they lived in, the old brick terraces and tenements of inner London. Yet as I grew up my father peopled the little house where he grew up in our imaginations. He told us of the eleven others living there, of sharing his bedroom with his Uncle Sam, who he didnt talk to. He refused to talk to Sam because, he said, he, Harold, had come home with a hat from the Lane Petticoat Lane Market and Sam had turned it inside out and back again, and spoilt it. In the language that they spoke before I was born, Yiddish, he and Sam were broygus not talking. Broygus but sharing a bedroom.

It was into this house in Nelson Street, behind the London Hospital in Whitechapel, that Harold arrived on a boat from America in 1922, aged three. He came with his older sister Sylvia, his younger brother Wallace and their mother, Rose. This was half a family. The other half stayed in the States. Harolds father Morris, a factory boot and shoe worker, stayed behind with my fathers elder brothers Sidney and Laurence. My father only ever saw Laurie again the others never though the story always was that one day Morris would come. He never did.

Harolds mother, Rose, the woman he called Ma, was an extraordinary, perhaps outrageous, person. The family story says that on the day she left America, these two oldest sons were working in the fields near to the row house where the family lived in Plymouth Street, Brockton, Massachusetts. Rose gathered together my father aged three, the baby Wallace and my fathers sister Sylvia aged five, and headed off without even saying goodbye to the boys in the field.