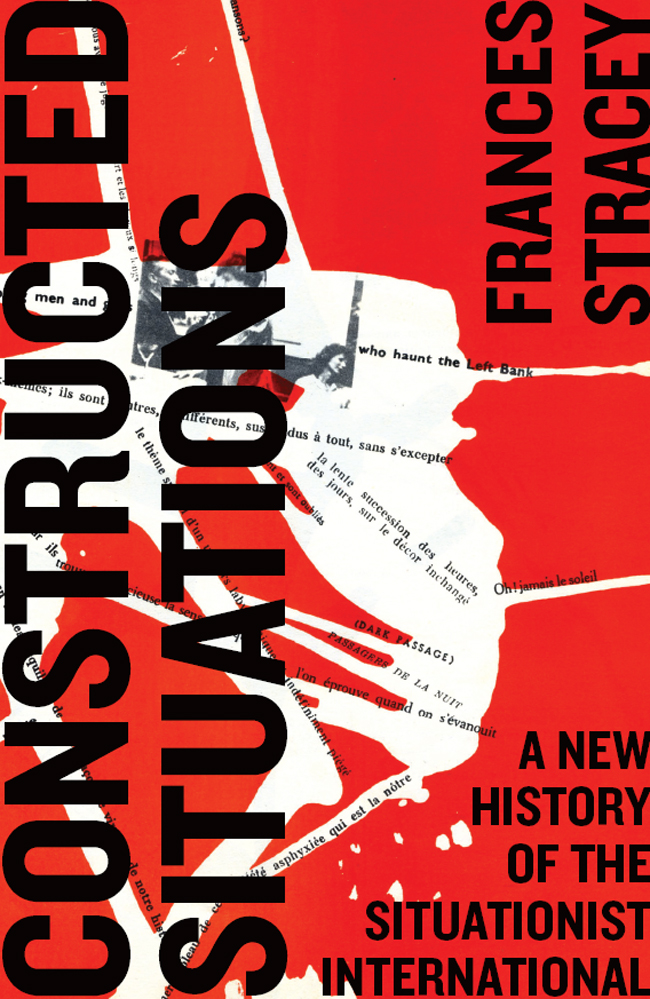

CONSTRUCTED SITUATIONS

Marxism and Culture

Series Editors:

Professor Esther Leslie, Birkbeck, University of London

Professor Michael Wayne, Brunel University

Red Planets:

Marxism and Science Fiction

Edited by Mark Bould and China Miville

Marxism and the History of Art:

From William Morris to the New Left

Edited by Andrew Hemingway

Magical Marxism:

Subversive Politics and the Imagination

Andy Merrifield

Philosophizing the Everyday:

The Philosophy of Praxis and the Fate of Cultural Studies

John Roberts

Dark Matter:

Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture

Gregory Sholette

Fredric Jameson:

The Project of Dialectical Criticism

Robert T. Tally Jr.

Marxism and Media Studies:

Key Concepts and Contemporary Trends

Mike Wayne

CONSTRUCTED SITUATIONS

A New History of the Situationist International

Frances Stracey

For Peanut

First published 2014 by Pluto Press

345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA

www.plutobooks.com

Copyright the Estate of Frances Stracey 2014

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 7453 3527 8 Hardback

ISBN 978 0 7453 3526 1 Paperback

ISBN 978 1 7837 1223 6 PDF eBook

ISBN 978 1 7837 1225 0 Kindle eBook

ISBN 978 1 7837 1224 3 EPUB eBook

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for

This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England

Text design by Melanie Patrick

Simultaneously printed digitally by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham, UK and Edwards Bros in the United States of America

CONTENTS

FIGURES

SERIES PREFACE

Marxism and Culture is the name of our book series. The Situationists stand askew to both these terms and that is why they are of interest to us. The Situationists ingested Marx, his dialectics, his commitment to revolution, his searing tones of critique and caustic prose, his chiasmic formulations. But they were not Marxologists, defenders of the faith. Marxism came back to life in their raging analyses. They were interested in slamming into their moment, making it liveable, handling Marx as if handling stolen goods. And, as for culture, that was something they made, destroyed, rated above all else and despised, sometimes sequentially, sometimes all at the same time. They were more aesthetic than the aesthetes, more luxurious than the deluxe-edition types. But in a way that junked, mocked, remixed or scorned the culture of the past and present. They paid homage to a few and upset more.

The Situationists remain a resource and a rebuke to any efforts to think and act as revolutionaries in the field of culture. Despite their critique of recuperation, they provide a touchstone for attempts to give cultural expression to revolutionary ideas even after the designation of Guy Debords archive as a National Treasure of France, when it was acquired, in 2011, by the Bibliothque nationale de France. History may have rendered positive the most negative of critics and the movement he mobilized, but their successes and failure, which is a social one, still provide many pertinent lessons.

The Situationists were the most cultured of all and the most revolutionary. It was the force-field between these two aspects that powered their thought. Even when art was ostensibly abandoned in favour of theoretical-political analysis, it shadowed the political theory as a or its negative image. Too frequently the counter-parts of art and politics have been broken apart in interpretations of the Situationist legacy: artists alight on the aesthetic aspects, the avant-garde techniques, the questions of recuperation of culture; politicos debate the questions of form, the analysis of the state, the legitimacy or not of the vanguard party. Sometimes the praxis and theory of the Situationists floats free of the demands of its moment, in dehistoricized accounts. Frances Straceys Constructed Situations holds it all in play and, more than that, it observes the shingling of aesthetics in politics and sets everything firmly in specific constructed situations that constitute Situationist theoretical practice. These collective acts of counter-cultural and political assault include photo-graffiti, industrial painting, the JornDebord collaboration Mmoires, the first and only Situationist group exhibition titled Destruktion af RSG-6, held at the Galerie EXI in Odense, Denmark in June 1963, writing and editing a journal, inventing strategies for evading the archive, and theorizing and advocating riots. The scintillating moments of cultural and revolutionary collaboration that comprise the chapters here explore the Situationists mode of phenomeno-praxis, in which art and politics are united in a lived event.

The ideas in this book began life as a thesis at University College London, titled Pursuit of the Situationist Subject. They evolved substantially after the thesis submission in 2001, as Stracey, who had studied art and had worked as a medical photographer and librarian, spent several years turning parts of the chapters into journal articles or contributions to edited volumes. In 2005, she reconceived the thesis as a book organized around the notion of constructed situations. She managed to complete a full draft of the book before dying of cancer in November 2009.

The fact that it has taken some time for the book to be published is no disadvantage. The pressure points of our moment are caught here as they form, rendering the book prescient, yet not sectarian. There is exploration of what a materialist Marxist feminism might look like and how it might relate to representations of sexuality. There are discussions of labour and its refusal, which address some of the debates around modes of labouring, immaterial labour, over- and under-employment and art making as a form of industry, in all senses. Under the motto Never Work, a critical cartography of shifting work relations proposes how the production of life might appear at the heart of a critique of capitals management of alienated labour a proposal that only gains in urgency. There are investigations of social reproduction and the role of women in reproducing the conditions of the future. There is dedication to exploring and advocating modes of revolutionary subjectivity, an ever re-articulated quest so necessary to overcome the tedium of much leftist politicking. There are contributions to debates around the party form and political organization which segue with those now taking place in an ever more fissiparous left, in which new accords between anarchists, communists and socialists occur. There is sustained reflection on the stakes of being archived, which is now most definitely not an academic question posed regarding the Situationist legacy. The book ends at a point when the ideas that are now more familiar to some of us some even fading into memory struck the world as incipient forms, as revivals of Situationist thought and practice: Reclaim the Streets, early digital art hacktivism, the forces that would combine in Occupy. To recover the potential that those movements offered in their time allows us, now, to invent new modes of vivification of these still charged ideas.