Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Philip Hamilton McMillan of the Class of 1894, Yale College.

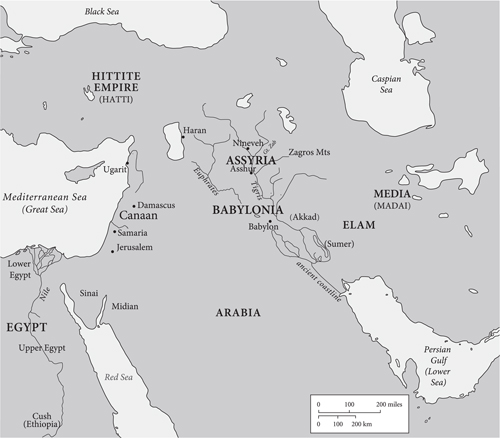

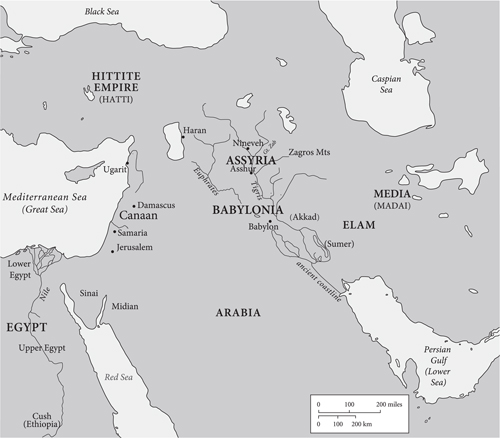

Frontispiece: The ancient Near East, significantly adapted from Israel and Ancient Trade Routes, in Oxford Bible Atlas, 4th ed., ed. Adrian Curtis (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 67.

Copyright 2014 by David M. Carr.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Designed by James Johnson.

Set in Walbaum Roman type by IDS Infotech, Ltd.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Carr, David McLain, 1961. Holy resilience: the Bibles traumatic origins/David M. Carr.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-20456-8 (hardback)

1. BibleHistory. 2. SufferingBiblical teaching. 3. SufferingReligious aspectsJudaism. 4. SufferingReligious aspectsChristianity. I. Title.

BS445.C37 2014

220.6dc23

2014009144

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to all haunted by suffering,

especially those haunted by experiences

of war

The spaces which are unwritten are anything but empty. They are the places where deeper power lives, where the more of living experience refuses to be ruled by the less of what can be written. These unwritten spaces pull with the power of a stars gravity, drawing everything into orbit around themselves. It is around the unwritten spaces that the texts rotate. The lived world is stronger than the authorized world. It is around the lived world that the texts of authorization revolve as lesser satellites, although a Ptolemaic imagination believes otherwise.

DOW EDGERTON,

The Passion of Interpretation

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

PREFACE

I OFFER THIS BOOK as a synthesis of research on the Bible and an experiment in supplementing such scholarship with research on trauma and memory. Though I could have added qualifiers to many more sentences in the book, readers should just take note that the whole represents my considered judgment on issues of continuing discussion. The translations of Hebrew texts throughout are my own, while translations of the Greek are drawn or adapted from the New Revised Standard Version unless otherwise noted.

Writing this book, I felt surrounded by a cloud of witnesses of people, near and far, who have been traumatized. Some such traumas are named and known, while many others are not. As a Quaker, I am especially conscious of those who have suffered and are now suffering in warthe war on terror, the war on drugs, and more conventional wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and many other places. Others may read this book with their own cloud of witnesses or personal experiences of trauma. Though I write here about ancient trauma, I dedicate this book to those who have experienced trauma more recently.

Introduction

W HEN MY WIFE and I rolled out on a spectacular Columbus Day weekend, 2010, thoughts of biblical research were far from my mind. It was our tenth anniversary, and we were meeting some friends for a bike ride in the Catskill Mountains of New York. Just a half-hour into our ride my bicycle fell apart on a downhill. The impact on pavement left me with ten broken ribs, a broken collarbone, a collapsed lung, and months of healing and rehabilitation ahead. I lived, barely. The thoracic surgeon who eventually rebuilt my chest with six platinum plates said that I was the only patient he knew who had survived the level of chest trauma he saw. He speculated that this was due to conditioning Id built up as an amateur bike racer. In the months to come I remained haunted with images of what life might have been like for my family and friends if I had died.

My thesis was that contemporary studies of trauma could explain characteristics of prophetic books written in the context of the exile of Jews in Babylon. As a biblical scholar, I was acutely aware, of course, of differences between ancient Israelite experiences of suffering and contemporary experiences labeled traumatic. Still, humans started experiencing trauma a long time before trauma studies began. The more I read psychological, anthropological, and other studies of trauma, the more I have come to believe that they can teach me and others about how this ancient Israelite people suffered and how their experiences live on with us through the Bible.

The accident, combined with my reading on trauma, allowed me to see the Bible with fresh eyes. It sensitized me to ways that both the Jewish and Christian scriptures were formed in the context of centuries of catastrophic suffering.

Here I tell the story of how the Jewish and Christian Bibles both emerged as responses to suffering, particularly group suffering. Both Judaism and Christianity offer visions of religious life that emphasize religious community, whether Moreover, the Jewish and Christian scriptures define these communities in ways that have helped these communities endure catastrophe, rather than be devastated by it. Perhaps most important, the scriptures of Judaism and Christianity, written in part as a response to communal suffering, present suffering as part of a broader story of redemption. In complicated ways, each tradition depicts catastrophe as a path forward. This is the kind of religious perspective, for example, that can include the exhortation by Jesus, If any want to become my followers, let them take up their cross and follow me (Mark 8:34; parallels in Matt 16:24; Luke 9:23).

The cross of Jesus, of course, is just one of many painful episodes that fed into the Bible, some better known than others. First, the Assyrians, an efficient and terrifying empire based in what is now northern Iraq, destroyed the Northern Kingdom of Israel and almost destroyed the kingdom of Judah to the south. The Assyrians then dominated Judah for almost a century. Next, another Mesopotamian empire, the Babylonians, destroyed Jerusalem and deported its population to remote parts of Babylon. A few decades later the Persian Empire defeated the Babylonians and allowed a few Judean exiles to trickle back home to Jerusalem. These returnees, however, never regained their Davidic kings or statehood. Instead, they formed a Temple-centered community shaped by lessons learned while in exile in Babylon. Centuries later a Hellenistic king, Antiochus the fourth, gained control of Judah, rededicated the temple to a Greek god, and enforced the death penalty for anyone practicing Judaism. Though his rule was eventually ended by the Maccabean revolt, Judah soon fell under the power of Rome. And this set the stage for the crucifixion of Jesus and other Jews convicted of rebellion, the eventual destruction of Jerusalem, and Roman criminalization of the emergent Jesus movement.

Next page