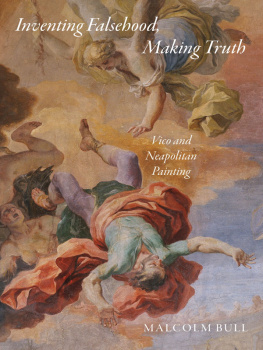

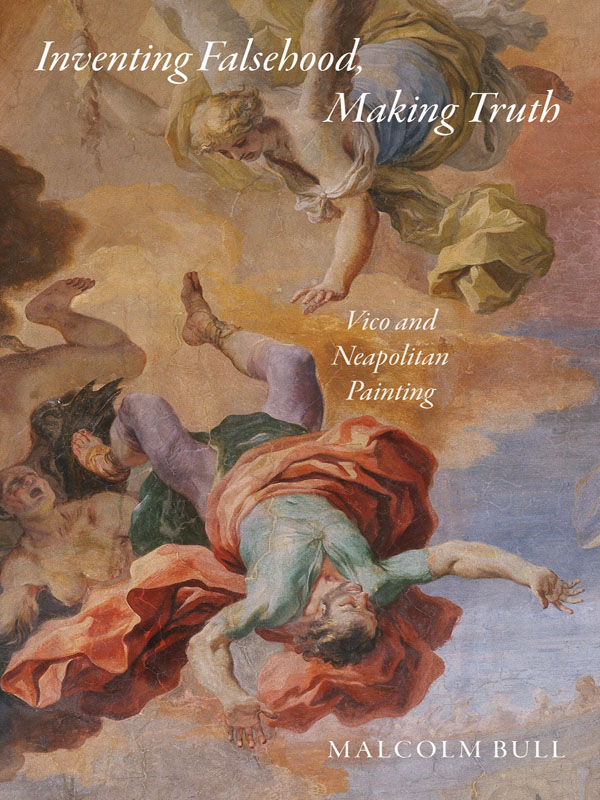

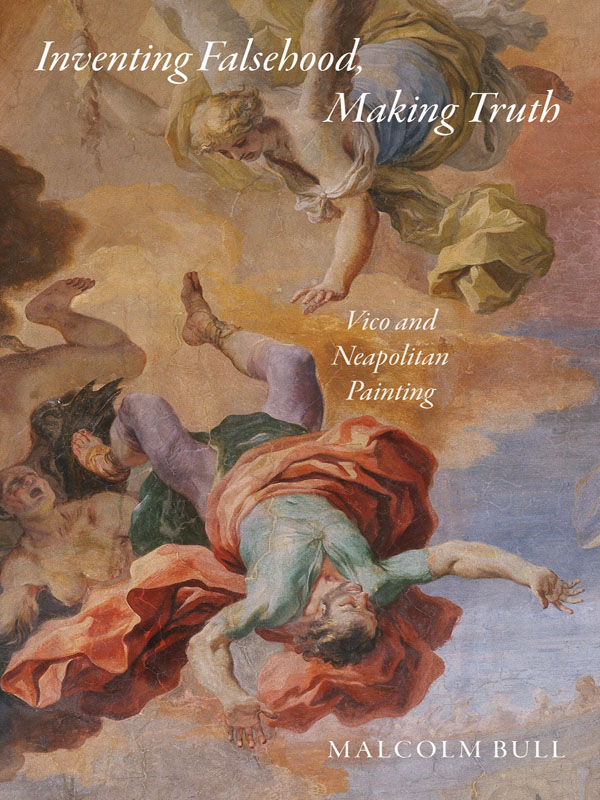

Inventing Falsehood,

Making Truth

ESSAYS IN THE Arts

Also in this series

WartimeKiss, by Alexander Nemerov

MutePoetry, Speaking Pictures, by Leonard Barkan

The Melancholy Art, by Michael Ann Holly

Inventing Falsehood,

Making Truth

Vico and Neapolitan Painting

MALCOLM BULL

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2013 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket Art: Francesco Solimena (16571747), detail of The Fall of Simon Magus.

Photo: Luciano Romano. S. Paolo Maggiore, Naples, Italy. Photo Credit: Scala / Art Resource, NY

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bull, Malcolm.

Inventing falsehood, making truth : Vico and Neapolitan painting / Malcolm Bull.

pages cm. (Essays in the arts)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-13884-8 (hardback)

1. PaintingPhilosophy. 2. Art and philosophyItalyHistory18th century. 3. Painting, ItalianItalyNaples18th century. 4. Painting, BaroqueItalyNaples. 5. Vico, Giambattista, 16681744. 6. Truth. I. Title.

ND1140.B78 2013

759.573dc23 2013015837

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Garamond Premier Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Jill

Contents

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to T. J. Clark, who posed the question this book attempts to answer, and to Hanne Winarsky of Princeton University Press for unexpectedly providing an opportunity to address it. Two long-standing interlocutors, David Carrier and Tom Nichols, encouraged the project from its inception. I am also grateful to Kristina Blagojevitch, who did the picture research, and to the editors at Princeton University Press who brought the manuscript to publication. The book is dedicated to Jill Foulston, my companion in Naples and elsewhere.

Prologue

T he epigraph to the first chapter of E. H. Gombrichs Art and Illusion is a quotation from the eighteenth-century Swiss artist Jean-tienne Liotard: Painting is the most astounding sorceress. She can persuade us through the most evident falsehoods that she is pure Truth. Gombrich argues that painters persuade viewers through their mastery of the techniques of illusion. This book explores another aspect of paintings magic: not its ability to simulate truth, but its capacity to change our perception of what truth is.

According to the Egyptologist Jan Assmann, the formative distinction in European civilization is the Mosaic one between religions that are true and those that are false. The crucial innovation that history attributes to Moses is not the categorization of particular religions as true or false but rather the concept of a truth that does not supplement or augment other truths, but places everything else in a relation to untruth itself. Before the Mosaic distinction, there were no false religions; thereafter, if one god was true, the others were false.

The Mosaic distinction was inherited by Christianity. Because Christianity was true, pagan religion was false, and in the course of a few centuries, the religions of the Greco-Roman world were eradicated. This meant that pagan idols were false too, and so they were destroyed as well. The position of nonpagan images was more ambiguous, but they were always suspect. As the eighth-century Libri carolini put it:

Truth persevering always pure and undefiled is one. Images, however, by the will of the artist seem to do many things, while they do nothing... it is clear that they are artists fictions and not the truth of which it is said: And the truth will make you free.

With varying degrees of theological urgency, images, idols, and false gods all posed the same philosophical problem: they represented things that did not exist. In this context, the increase in the number of images in the Renaissance, and the revival and diffusion of themes from classical mythology, embodied a complex challenge to Christian conceptions of truth. Painting was false because it was a representation rather than the reality, and mythological painting was doubly false because the things it representedthe gods and monsters of the ancient worldwere themselves unreal.

The presence within early modern Europe of an entire strand of cultural production that no one believed to be true put the Mosaic distinction under a degree of pressure. There were a variety of responses, ranging from iconoclasm to outright skepticism. But for one thinker, this explosion of images did not pose a problem; it suggested a solution. According to Giambattista Vico, writing in 1710, human truth is actually like a painting. It is an astonishing claim if you set it alongside Daniello Bartolis account of why his contemporaries prized paintings:

That is just what Liotard was referring to when he said that painting... can persuade us through the most evident falsehoods that she is pure Truth. But could painting ever be so persuasive as to persuade us that truth itself functions the same way?

Inventing Falsehood,

Making Truth

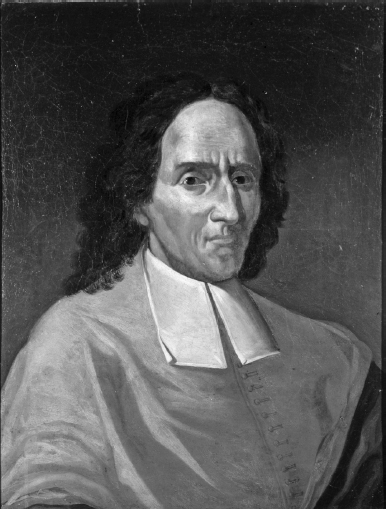

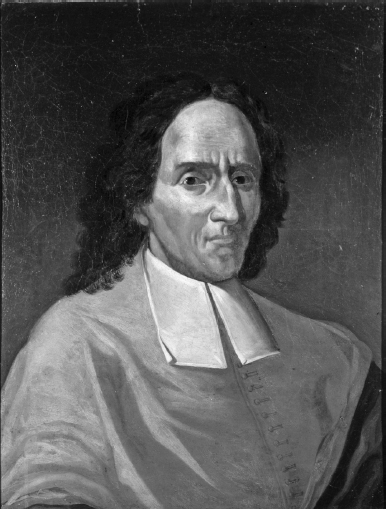

1.1.

After Francesco Solimena, Portrait of Giambattista Vico, Museo di Roma, Rome ( 2013 White Images / SCALA, Florence).

ONE

Vico

G iambattista Vico ( Due to ill health, his education was a little haphazard, conducted partly at home and partly with the local Jesuits. He was an able student, however, and from 168695 he was employed as a private tutor, spending much of his time outside of Naples at the Rocca family property at Vatolla. During this period he was also enrolled in the faculty of jurisprudence at the University of Naples, from which he graduated with a doctorate in canon and civil law in 1694.

In 1699 he was appointed professor of rhetoric in the university and in this capacity delivered an annual inaugural oration; the seventh of these, Study Methods of Our Time, became his first significant publication in 1709, quickly followed by On the Ancient Wisdom of the Italians in 1710. Vico taught courses in rhetoric, from which his students notes survive, now published as The Art of Rhetoric. However, he had larger ambitions, and set his sights on the more prestigious, and much better paid, chair of civil law. With this in mind he published the three treatises that make up his Universal Right (172022). But in 1723 the job was given to someone else, and he remained in the chair of rhetoric until succeeded by his son in 1741.

Though he gave up hope of finding a better position in Naples, Vico was an active member of the various academies around which the flourishing intellectual life of the city centered in the early eighteenth century. And despite the fact that he never traveled, he had a measure of international recognition. There had been a favorable review of the first two parts of Universal Right in the Bibliothque Ancienne et Moderne, a leading journal with a European readership, and Vico was clearly sufficiently well known to be asked to contribute an account of his intellectual development to a projected series of autobiographical writings by scholars, published in Venice in 1728. His major work, the

Next page