This book made available by the Internet Archive.

For my father, Louis DeWald Sass

and in loving memory of my mother,

Hrafnhildur Einarsdottir Arnorsson Sass

(September 11, 1915-January 1, 1964)

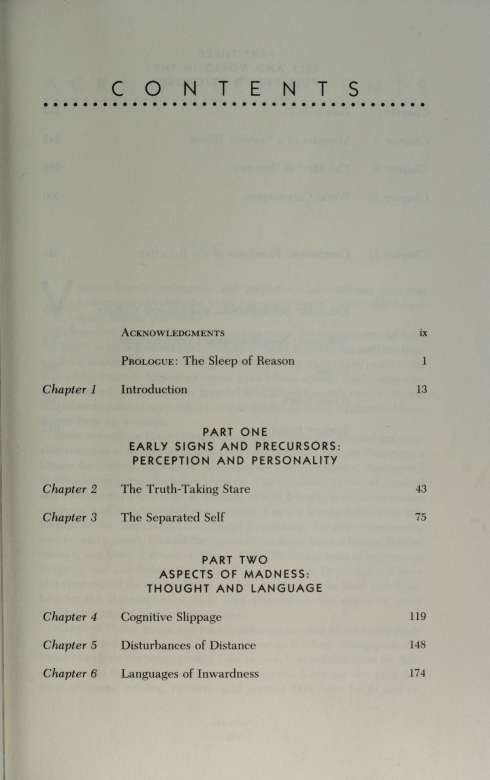

PART THREE SELF AND WORLD IN THE FULL-BLOWN PSYCHOSIS

Chapter 7 Loss of Self

Chapter 8 Memoirs of a Nervous Illness

Chapter 9 The Morbid Dreamer

Chapter 10 World Catastrophe

213 242 268 300

Chapter 11 Conclusion: Paradoxes of the Reflexive

Epilogue: Schizophrenia and Modern Culture 355

Appendix: Neurobiological Considerations 374

Notes 399

Name Index 563

Subject Index 583

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Various friends, colleagues, and institutions have offered help and encouragement over the years (too many years, I fear) that I have spent writing this book.

Fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities and from the Institute for Advanced Study (School of Social Science) released me from teaching responsibilities at the important beginning stage of the project; the year at the Institute helped set me on a track from which I might otherwise have wavered. I am especially grateful for Clifford Geertz's support at that crucial early point in my work, as well as for the enduring inspiration I have drawn from his writings.

More recently, a Henry Rutgers Research Fellowship granted me valuable stretches of writing time, and a year as a fellow of Rutgers University's Center for Critical Analysis of Contemporary Culture afforded time as well as stimulating interdisciplinary contacts. The Graduate School of Applied and Professional Psychology at Rutgers, where I teach, is an uncommonly congenial and broad-minded environment. I owe a special debt to my colleagues in the Department of Clinical Psychology; for their unwavering interest and support, I would like especially to thank Sandra Harris, Stanley Messer, and Donald Peterson (Dean of GSAPP during most of my time at Rutgers), and also Robert Woolfolk of the Psychology Department. I have also appreciated the collegiality of my fellow fellows at the New York Institute for the Humanities (at New York University), the source of many memorable lunches for some years now.

Margaret Thaler Singer and John Gunderson introduced me to the study of schizophrenia and supported my early research efforts (along quite different lines from the present book). I am extremely grateful to them for their kindness, and for openheartedly encouraging me to follow my own path. My years of clinical training, research, and practice have been fertile and re

warding, and I extend thanks to the supervisors, colleagues, and patients with whom I have worked at several institutions: New York Hospital-Westchester Division (Cornell Medical Center); McLean Hospital-Harvard Medical School; the Psychology Department at the University of California, Berkeley; the Charles Drew Family Life Center; and Boston State Hospital. I am also grateful to several friends and acquaintances who spoke to me of the mt own experiences with schizophrenia.

Many people were kind enough to read and comment on versions of these chapters over the years. Although I can't thank all of them here, I would like to mention Sidney Blatt, John Boyd, John Broughton, Bertram Cohen, Philip Cushman, Hubert Dreyfus, Allan Eisenberg, Melvin Feffer, Angus Fletcher, John Gittins, Jim Gold, Howard Gruber, Erich Heller, Wolf Lepenies, Michael Leyton, James Phillips, and Michael Schwartz. Philip Fisher, my tutor in English literature when I was an undergraduate, helped inspire my interest in modernism; and my sister, Ann Sass, was an important early influence on my developing interest in the visual arts. My father's influence, particularly in matters of intellectual style, has been especially profound.

Steve Fraser, my editor at Basic Books, has offered astute and invaluable editorial advice at several stages of what turned out to be a very lengthy process. I would like to thank him for his early encouragement, for his patience throughout the writing process, and for a much-needed push toward completion. I would also like to extend my thanks to Linda Carbone for her meticulous and acutely intelligent attention in the final editing and preparation of the manuscript.

Over the years, Jamie Walkup, a generous-spirited friend and incisive critic, cheerfully read drafts of all the chapters. He offered many thoughtful and useful suggestions as well as endless access to his vast store of knowledge in several fields. I thank him for many hours of enjoyable discussion, and also for saving me from more than a few errors of fact and interpretation.

Finally, I am deeply grateful to Shira Nayman, who has aided me immeasurably since an early stage in the project. She has read and reread all my chapters, has joined in worrying through the arguments, and, most important, has helped to quiet my own critical voices. This would have been a less interesting book, and the task of writing it far more onerous, without the benefits of her keen editorial eye and literary judgment, her invigorating curiosity, and the great pleasure of her companionship.

Note: Quoted material from patients that is not otherwise attributed comes from patients I have treated or interviewed, or to whom I administered psychological tests. All patients' names not from the literature are, of course, pseudonyms.

A great deal of supplementary materialsupportive references, additional examples, qualifications, elaborationscan be found in the extensive notes section.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The growing consciousness is a danger and a disease.

Friedrich Nietzsche

PROLOGUE

The Sleep of Reason

The madman is a protean figure in the Western imagination, yet there is a sameness to his many masks. He has been thought of as a wildman and a beast, as a child and a simpleton, as a waking dreamer, and as a prophet in the grip of demonic forces. He is associated with insight and vitality but also with blindness, disease, and death; and so he evokes awe as well as contempt, fear as well as condescension and benevolent concern. But the variousness of these faces should not be allowed to obscure their underlying consistencies, for there are certain assumptions about insanity that have persisted through nearly the entire history of Western thought.

Madness is irrationality, a condition involving decline or even disappearance of the role of rational factors in the organization of human conduct and experience: this is the core idea that, in various forms but with few true exceptions, has echoed down through the ages. Nearly always insanity has been seen as what one early-nineteenth-century alienist called "the opposite to reason and good sense, as light is to darkness, straight to crooked." 1 And, since reason has generally been seen as the distinctive feature of human nature itself, it would seem to follow that madmen must be not merely different but somehow deficient in essential qualities of humanity or person-hood. 2 Indeed, the very word reason means both the highest intellectual faculty and the sane mind.