WHAT IS ESOTERICISM?

Strictly speaking, the term esoteric refers to knowledge reserved for a small group; it derives from the Greek word esotero, meaning within, or inner. In our context, the word esoteric implies inner or spiritual knowledge held by a limited circle, as opposed to exoteric, publicly known or outer knowledge. The term Western esotericism, then, refers to inner or hidden spiritual knowledge transmitted through Western European historical currents that in turn feed into North American and other non-European settings. Defined in this simple way, esoteric knowledge can be traced throughout Western history from antiquity to the present, even if it is richly varied in kind, ranging from the Mysteries of ancient Greece and Rome to Gnostic groups to Hermetic and alchemical practitioners, all the way to contemporary esoteric groups or new religious movements.

Characteristic of esotericism is a claim to gnosis, or direct spiritual insight into cosmology or metaphysics. This characteristic has the advantage of being broad enough to include the full range of esoteric traditions, but narrow enough to exclude exoteric figures or movements. Furthermore, such a traditional term preserves the distinction between conventional or mostly rationally obtained knowledge on the one hand, and gnosis on the other. Alchemists search for direct spiritual insight into nature and seek to transmute certain substances thereby; astrologers seek direct spiritual insight into the cosmos and use it to analyze events; magicians seek direct spiritual insight and use it to affect the course of events; theosophers seek direct spiritual insight in order to realize their own angelical nature. But in all cases, aspirants seek direct spiritual insight into the hidden nature of the cosmos and of themselvesthey seek gnosis.

Esotericism refers, then, to the various traditions that emerge around these various approaches to gnosis, and one could as accurately refer to Western gnostic as Western esoteric traditions. Western esoteric traditions broadly speaking are, of course, widely varied in form and nature, but as we see below, they all have in common:

- gnosis or gnostic insight, i.e., knowledge of hidden or invisible realms or aspects of existence (including both cosmological and metaphysical gnosis) and

- esotericism, meaning that this hidden knowledge is either explicitly restricted to a relatively small group of people, or implicitly self-restricted by virtue of its complexity or subtlety.

In other words, Western esoteric traditions, generally speaking, entail secret or semisecret knowledge about humanity, the cosmos, and the divine.

MAGIC AND MYSTICISM

Both the words magic and mysticism remain somewhat nebulous. Scholars continue to disagree about what magic is, and for that matter, about what mysticism is. Commonly, of course, magic is held to do with achieving worldly aims through supernatural means; and mysticism is seen as a term describing those who seek and who claim to realize union with the divine. Yet these are problematic distinctionsmany magicians seem rather mystical in inclination; and conversely, some mystics seem rather close to magic in what they espouse or claim. To give two examples: the well-known Book of Abramelin the Mage edited by S. L. MacGregor Mathers includes a ritual of seclusion and of a kind of mysticism (seeking union with ones guardian angel) that on the face of it does not seem to belong to magic so much as to mysticism. And one might also note the assertion of John Pordage (16081681) at the end of his Letter on the Philosophic Stone that one who followed his path of spiritual alchemy will become a magus. This is the expected achievement of one who follows the counsel of Pordage, arguably the greatest mystic of the theosophic tradition after Jacob Bhme! Clearly it is not as easy as it might seem to divide mysticism and magic into two discrete categories.

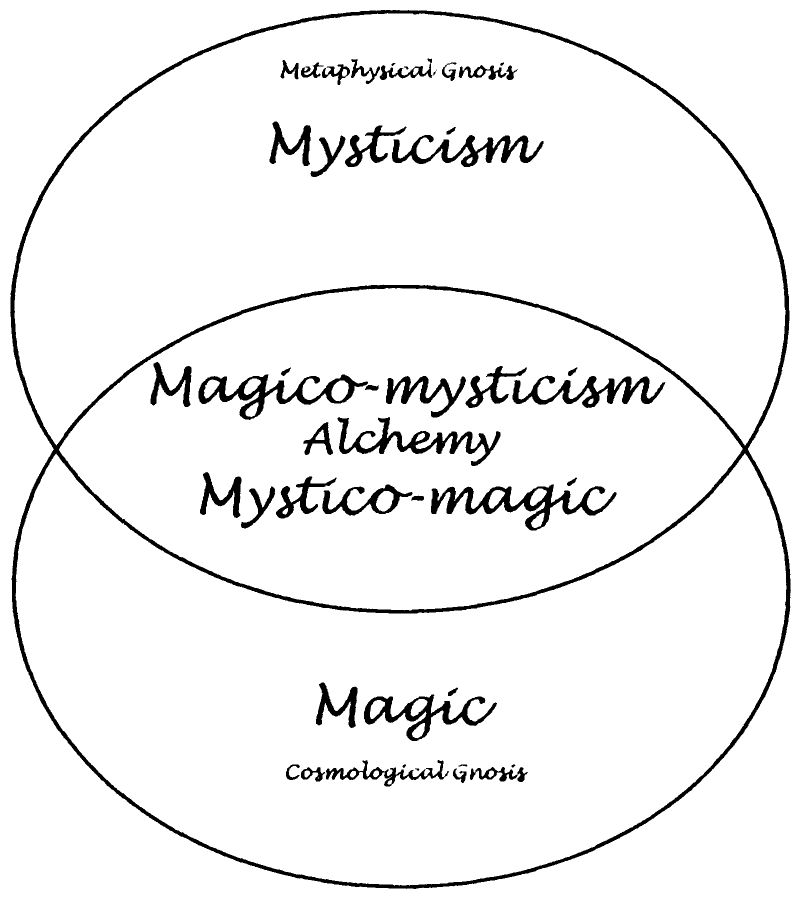

Still, we may broadly say that esoteric traditions tend to belong to one of two general currents: outward, toward cosmological mysteries, or inward, toward spiritual knowledge or knowledge of the divine. Of course, these two tendencies should not be too strictly interpreted, since they often overlap or merge. But one can distinguish roughly between magical traditions whose primary aims are essentially cosmological in naturethat is, more or less worldly in the sense of garnering wealth or powerand mystical traditions that explicitly reject worldly aims in favor of inner or spiritual illumination. This distinction is a fundamental one in the West, and we can see it recurring again and again. A mystic like Eckhart and a medieval magus or necromancer do belong to different currents, not least because whereas Eckhart seeks divine wisdom, the magus seeks cosmological knowledge or power. Magic has to do with power over others or over nature; often, the magician seeks to command. Mysticism, on the other hand, has to do with the surrender and transcendence of self and of power; the mystics primary interest is not in worldly command but in realization of the divine.

Both magic and mysticism belong under the broad rubric of esotericism because both magicians and mystics pursue or claim esoteric knowledge that belongs only to them or to their tradition. They themselves exclude the hoi polloi and lay claim to inner or secret knowledge. Indeed, we can go further than that: for we may also say that magic and mysticism form the twin currents that, like the intertwined serpents of Hermess caduceus, together make up much of the stream of Western esotericism. On the one hand, we have the current of cosmological gnosis to which belongs not only magic, but also alchemy, astrology, the various mancies like geomancy or chiromancy, and all those other forms of secret or semisecret knowledge of the cosmos. And on the other hand we have the current of metaphysical gnosis, the most lucid form of which is the negative mysticism of Dionysius the Areopagite or Meister Eckhart. Together, these two currents, which intertwine and separate, form the larger field of Western esotericism.

Put another way, magic and mysticism represent the ends of a spectrum that we may term Western esotericism, and most esoteric figures and groups are to be found in the middle, that is, incorporating aspects of both (see While we can find examples of a theosophical-theurgical model in Western esotericism, especially in the lineage of Jacob Bhme, examples of mystico-magical or magico-mystical models are much more widespread. Understood in this way, alchemical writings, for instance, may be neither a mystical code nor a magical protochemistry, but partake of both currents at once.