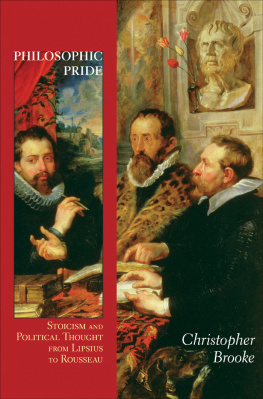

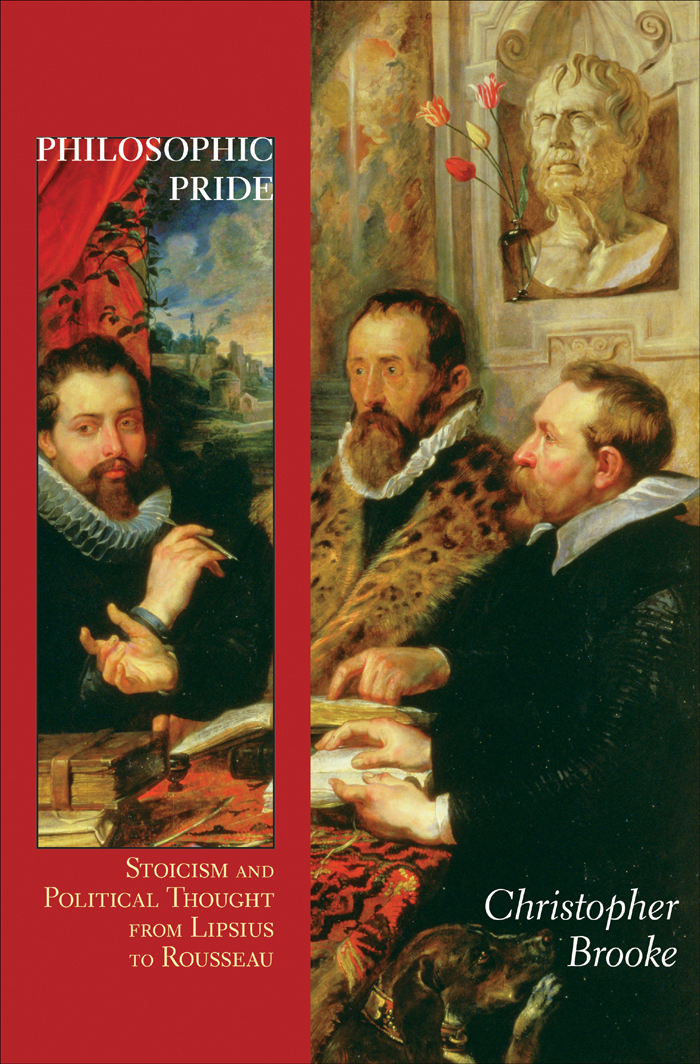

Philosophic Pride

Philosophic Pride

STOICISM AND POLITICAL THOUGHT FROM LIPSIUS TO ROUSSEAU

Christopher Brooke

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2012 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket illustration: The Four Philosophers, c. 161112 (oil on panel), by Peter Paul

Rubens (15771640); Palazzo Pitti, Florence, Italy. Reproduced courtesy of

The Bridgeman Art Library; photo copyright Alinari

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brooke, Christopher, 1973

Philosophic pride : Stoicism and political thought from Lipsius to Rousseau / Christopher Brooke.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. 253) and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-15208-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)1.Political sciencePhilosophyHistory.I.Title.

JA71.B757 2012

320.01dc23

2011034498

This book has been composed in Sabon LT Std

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Josephine

The Stoic last in philosophic pride,

By him called virtue, and his virtuous man,

Wise, perfect in himself, and all possessing,

Equal to God, oft shames not to prefer,

As fearing God nor man, contemning all

Wealth, pleasure, pain or torment, death and life

Which, when he lists, he leaves, or boasts he can;

For all his tedious talk is but vain boast,

Or subtle shifts conviction to evade.

Alas! what can they teach, and not mislead,

Ignorant of themselves, of God much more,

And how the World began, and how Man fell,

Degraded by himself, on grace depending?

Much of the Soul they talk, but all awry;

And in themselves seek virtue; and to themselves

All glory arrogate, to God give none;

Rather accuse him under usual names,

Fortune and Fate, as one regardless quite

Of mortal things.

John Milton, Paradise Regaind, 4.300318

Contents

Augustine of Hippo

Justus Lipsius and the Post-Machiavellian Prince

Grotius, Stoicism, and Oikeiosis

From Lipsius to Hobbes

The French Augustinians

From Hobbes to Shaftesbury

How the Stoics Became Atheists

From Fnelon to Hume

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Preface

For ernst cassirer, writing in American exile during the Second World War, ideas drawn from Stoic philosophy played a vital role in the formation of the modern mind and the modern world. The Greek Stoics had taught that one should live in accordance with a moral law of nature, he observed, and the Roman Stoics had both championed the virtue of humanitas, absent from earlier Greek ethics, and argued for a cosmopolitanism that treated the whole world, gods and humans together, as fellow citizens of one great republic. In particular, Cassirer attributed to the Stoics the notion of the fundamental equality of all human beings. Stoic ideas persisted beyond the end of the Stoic school itself, Cassirer suggested, finding a place in Roman jurisprudence, in the Fathers of the Church, in scholastic philosophy. But it was only in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that these ideas took on tremendous practical significance. In the world of the Renaissance and the Reformation, the unity and the inner harmony of medieval culture had been dissolved, the hierarchic chain of being that gave to everything its right, firm, unquestionable place in the general order of things was destroyed, and the heliocentric system deprived man of his privileged condition. The prospects appeared bleak for a really universal system of ethics or religion, one based upon such principles as could be admitted by every nation, every creed, and every sect.

Stoicism alone seemed to be equal to this task. It became the foundation of a natural religion and a system of natural laws. Stoic philosophy could not help man to solve the metaphysical riddles of the universe. But it contained a greater and more important promise: the promise to restore man to his ethical dignity. This dignity, it asserted, cannot be lost; for it does not depend on a dogmatic creed or on any outward revelation. It rests exclusively on the moral willon the worth that man attributes to himself.

Cassirer thus considered seventeenth-century political philosophy to be in significant measure a rejuvenation of Stoic ideas. He highlighted the importance of works by Justus Lipsius and others, as well as the rapid passage of Neostoic ideas from Italy to France; from France to the Netherlands; to England, to the American colonies. Of the stirring opening phrases of the Declaration of IndependenceWe hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of HappinessCassirer claimed that When Jefferson wrote these words he was scarcely aware that he was speaking the language of Stoic philosophy.

What, then, was that Stoic philosophy? Stoicism was one of the philosophical systems that took shape in Athens in the so-called Hellenistic period following the death of Aristotle in 322 BCE. The first Stoic was Zeno from Citium, a Phoenician city on Cyprus, who came to Athens and studied with Crates the Cynic and other philosophers there, subsequently setting up his own school around the turn of the third century. This school met in the middle of Athens at the Stoa Poikil, or the Painted Stoaa stoa being a roofed colonnade or porticoand it was this structure that gave the philosophy its name. Zeno died in 262 and was succeeded as the head of the school, or scholarch, by Cleanthes, a former boxer. But it was his successor, the third scholarch Chrysippus of Soli, leader of the school during the final decades of the third century, who did more to systematise Zenos doctrines than any other philosopher, and who gave the Stoic philosophy its definitive form. Stoicism flourished in Athens and spread throughout the Greek and, later, Roman worlds.

Some of the characteristic doctrines of the Stoics were these: that God and the universe are coextensive with one anothera divine fire thoroughly permeates the world of stuffand this universe is a thoroughly rational totality. The physical world is all that exists, and all events in that world are causally determined. The goal of human existence is to live in accordance with nature, which is to live rationally or virtuously. Virtue is the only genuine good, and it is sufficient for happiness. Other things that we might conventionally call goods, such as health or wealth, are, properly speaking, only preferred indifferents. Vice is the only genuine bad. We must learn to distinguish between those things that are under our own control and those that are not, and train ourselves to be unconcerned about the latter. Most of the emotions that we experience are false judgements, and should be extirpated through Stoic therapies or spiritual exercises. If we can rid ourselves of these emotional responses, then we can live the good life in the passionless state the Stoics called apatheia, and to live that ideal life is to be the Stoics sage. But the Stoics conceded that the sage was rarer than the phoenix and might never in fact have existed. The sage was, they said, both wise and freea true cosmopolitan, or citizen of the worldand remained happy even under torture.