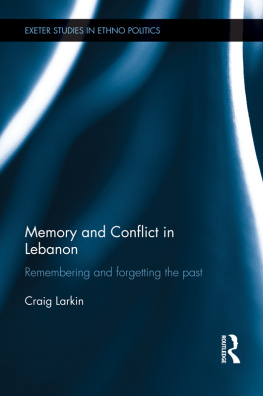

Remembering

Studies in Continental Thought

GENERAL EDITOR

John Sallis

CONSULTING EDITORS

Robert Bernasconi | William L. McBride |

Rudolph Bernet | J. N. Mohanty |

John D. Caputo | Mary Rawlinson |

David Carr | Tom Rockmore |

Edward S. Casey | Calvin O. Schrag |

Hubert Dreyfus | Reiner Schrmann |

Don Ihde | Charles E. Scott |

David Farrell Krell | Thomas Sheehan |

Lenore Langsdorf | Robert Sokolowski |

Alphonso Lingis | Bruce W Wilshire |

David Wood |

REMEMBERING

A Phenomenological Study

Second Edition

EDWARD S. CASEY

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

BLOOMINGTON AND INDIANAPOLIS

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

601 North Morton Street

Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA

http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress

Telephone orders 800-842-6796

Fax orders 812-855-7931

Orders by e-mail

1987 and 2000 by Edward S. Casey

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library

Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Casey, Edward S., date

Remembering : a phenomenological study / Edward S. Casey.2nd ed.

p. cm. (Studies in Continental thought)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-253-33789-5 (alk. paper) ISBN 0-253-21412-2 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Memory (Philosophy) 2. Phenomenology.

I. Title. II. Series.

BD181.7 .C33 2000

128'.3dc21

00-057231

1 2 3 4 5 05 04 03 02 01 00

To The Memory of

My Parents

Catherine J. Casey Marlin S. Casey

And in Remembrance of

the Vanished World of

My Grandparents

Daisy Hoffman Johntz John Edward Johntz

CONTENTS

Rethinking Remembering

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

From the start, I intended Remembering to be a companion volume to my earlier book Imagining, and it is gratifying to witness new editions of both books now appearing at the same time. This fortuitous event will underline what the two texts have in common: above all, a shared phenomenological orientation, a commitment to a close and detailed description of the various forms and directions taken by each act. The close comparison of imagining and remembering is hardly new; the two acts have been linked ever since Aristotles inaugural discussion of human mental activity. Hobbes, Hume, and Kant expressly yoked them together as alternative but complementary fates of perceptionits epistemic extension vis--vis past episodes (memory) or future happenings (imagination).

Although it is plausible to pair the two acts in this and other ways, by 1977a year after the publication of Imagining and a decade before the appearance of RememberingI had begun to discover basic differences between them that disallowed any claim (such as Humes) that they are both offshoots of perception, its direct or indirect copy. In an essay of that same year entitled Imagining and Remembering I maintained that despite their intimate collusion on many fronts (e.g., in the activity of the historian, in dreams, and in time-consciousness) they remain as distinct from each other as perception is from both. They differ from each other with regard to such fundamental things as the degree of familiarity they entail, their positing of content as existing or not, and their comparative corrigibility.

This is not to deny that the two acts are also significantly similar. Not only is neither parasitic on perception, but each is at once free and autonomous. Both submit to what I call intentional analysis, according to which each exhibits certain comparable modes of operation (e.g., imagining or remembering that something is the case; imagining or remembering how to do something); and each features a presentation that has both a specific content and a spatiotemporal world-frame, along with a characteristic mode of givenness. Nevertheless, even at this bare beginning level, important differences emerge. The autonomy of imagining is thin, that of remembering thick. Where intentional analysis uncovers only three basic act-forms of imagining, it detects many more kinds of remembering: e.g., primary and secondary, remembering to-do something, remembering on-the-occasion-of some event, remembering-as (i.e., my friend as depressed), remembering-what (e.g., what Burlington is like), etcetera. Rather than the specific content of what we remember being simply surrounded by a mere margin of indeterminacy as in the case of imagining, an entire atmosphere permeates what we remember. In remembering, there is a tenuous but consistently felt self-presence of the rememberer that inheres in And when it comes to eidetic analysis, there is the striking fact that, whereas describing the six essential features of imagining took up the major part of an entire book, the corresponding traits of remembering occupies only a short chapter of ten pages.

I

These various differences point to a larger truth: the mansions of memory are many. So polymorphic is remembering that no single set of intentional structures or eidetic features can capture the whole phenomenon. Primary traits (e.g., encapsulment/expansion) are continually complicated by secondary traits (e.g., schematicalness) which refuse to be reduced to the simplicity of any central description. No wonder Remembering is almost twice as long as Imagining; no wonder, either, that it took so long to write! I thought I could polish off this successor volume in several years; instead, it took a decade to write. Remembering itself proved me wrong. I had to face up to the paradox that imagining, often taken to be the quintessence of the quirky and the quixotic, showed itself to be more regular in its enactment and structure than remembering, usually assumed to be the more reliable and sober of the two acts.

As I settled into a more complex project than I had bargained for, I came upon a veritable proliferation of anomalies. Anomalies not construed as abnormalitiesthat is another matter, i.e., the pathology of memory, on which I shall touch belowbut as departures from accepted norms. Whereas it had been assumed by memory theorists as astute as James and Husserl that remembering comes in just two basic forms (primary or retentional vs. secondary or reproductive), it became clear to me that there is an entire set of intermediate forms of remembering: intermediate between primary and secondary memory, as well as between mind and world. These included such familiar (yet rarely investigated) kinds of memory as recognizing X as Y, being reminded of B by A, and reminiscing. Despite important differences, these mnemonic modes take us from the realm of mind to the larger reaches of the surrounding worldfrom the involuted concerns of mentation to the way the world shows itself to be filled with recognitory clues, effective reminders, and things that inspire reminiscence. Instead of memory being confined to mind aloneas its own root